|

|

||

|

The magazine didn’t just cover the glory years of suburban America, writes Steve Parnell – it helped to create them In 2008, Taschen published a reprint of every Arts & Architecture magazine from the decade between 1945 and 1954. Each one of the 6,076 pages – including adverts and front and back covers – was scanned, touched up and reprinted in a boxed-set facsimile format. The intention was to continue, reproducing the years up to the American journal’s demise in 1967, but it seems that the £450 limited edition didn’t sell as expected – this follow-up never appeared. But Taschen has not given up entirely on A&A, and its latest offering of mid-century-modern revivalism comes in a format that the publisher is much more comfortable with – extremely affordable high-quality reprints of iconic material. This new repackaging of the magazine’s content focuses on the years 1945 to 1949, and consists of a selection of choice pages from the magazine over those five years. The introduction states that Benedikt Taschen personally selected his favourite covers and stories, and hints that there will be several more hardcover volumes to come, in a manner similar to the 12 Domus volumes the firm published in 2006. This four-page introduction, written by David F Travers – the magazine’s editor from 1962 to 1967 – is the only commentary in the book. The remainder is comprised solely of hundreds of facsimiled pages.

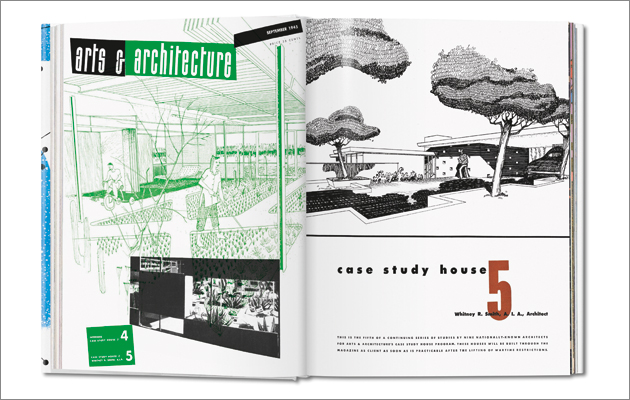

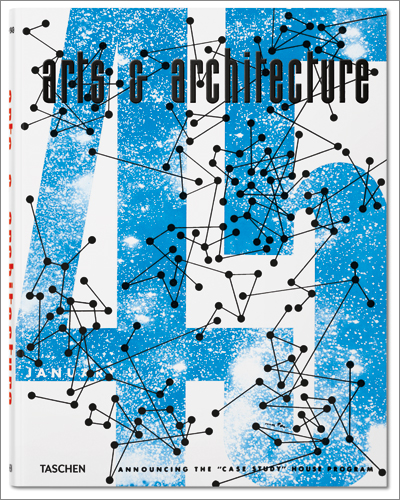

Taschen’s curated edition of magazine highlights from 1945–49 Bereft of context or interpretation, the material is organised chronologically. Without guidance, the reader is left to flick through without any real purpose other than to be awed by the mostly black-and-white design and graphics. There aren’t even page numbers or an index. The covers stand out as the main injection of colour and are stunning. Designed by modernist luminaries such as Charles Eames, Alvin Lustig and Herbert Matter, each one could be a poster in its own right. There is such an overwhelming richness of material here that it can be difficult to digest or comprehend, but the main narrative concerns A&A’s Case Study House (CSH) programme. You must have heard about the CSH programme, right? The ambition was for this small arts and architecture magazine to bring together architects, product manufacturers and end users, then publish both the designs and the results as built. It was envisaged that the programme would promote modern, low-cost, well-designed and replicable prototype houses using the latest in materials and technology, demonstrating how contemporary design could benefit the construction of a new post-war California. The CSH programme has become a touchstone in modern architectural design – plenty has been written about it, including architectural historian and A&A contributor Esther McCoy’s own paean, first published in 1962 while it was in full swing. The houses were photographed by rising stars in the architectural-photography constellation such as Ezra Stoller and, most famously, Julius Shulman, whose shots have since been widely published – for instance in Taschen’s own huge 2000 tome on the photographer, Modernism Rediscovered. Ironically, out of the 33 houses that were eventually published and 24 that were constructed, only one was ever replicated in built form. However, they now form a chunk of the modernist architectural canon, and Shulman’s photographs are some of the most reproduced images of modern architecture – think of Pierre Koenig’s Stahl House (CSH 22) overlooking the receding Beverly Hills lights or the Eames House (CSH 8), for example.

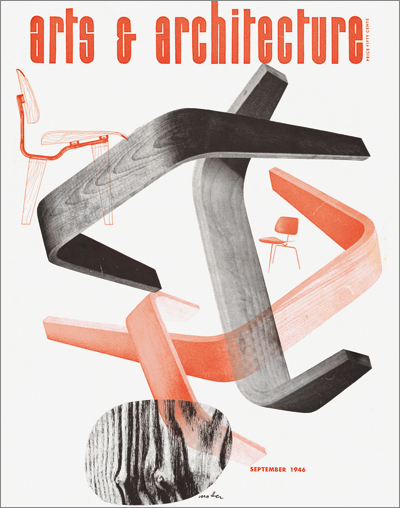

Arts & Architecture, September 1946, cover design by Herbert Matter The programme was a smart and bold thing to do. Both the enthusiasm and the experimentation surrounding the project can be clearly seen in the drawings and graphics presented in A&A. The plans suggest a freedom of lifestyle, and are complemented by lots of 3D sketches interspersed with adverts for furniture and construction products. These ads were also designed by the likes of Matter and Lustig, and often attain poster quality themselves. A&A’s editor at this time, John Entenza, was a lightning rod for talent – besides designers and photographers, he succeeded in attracting architects such as Eames, Koenig, John Lautner, Richard Neutra, Eero Saarinen and Craig Elwood, among others equally talented but less celebrated. The houses themselves display a distinct and modern Californian regionalism and unsurprisingly represent the epitome of the American suburban dream in its glory years, encompassing individualism, liberty and consumption. Each house is tailored to a generic American family unit – the head of the household who works nine to five, his domesticated wife, their two children, and a car or two. A certain easy-living lifestyle is depicted, serviced by technology and helped by eternally good weather – the sun always shines in this magazine and the architecture is defined as much by hard shadows as by a blurring of inside/outside space. Reading it 70 years later, it all feels ridiculously optimistic and smiley. So there is absolutely nothing new here – it has all been extremely well documented previously and much is available online. The resulting volume is completely uncritical and perhaps even cynical in its commodification of mid-century modernism, but it’s certainly a very affordable curation. |

Words Steve Parnell

Above: Spread from Arts & Architecture, September 1945, including Whitney R Smith’s CSH 5

Arts & Architecture: 1945–49 |

|

|

||