|

|

||

|

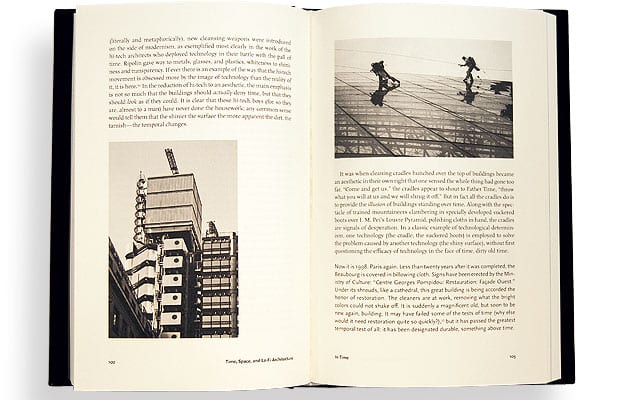

Architects need to be less autonomous and engage with the everyday, argues Jeremy Till, but this could well be a case of merry myth-making, says Charles Holland. Jeremy Till has a neat spatial metaphor for the aloofness of architects from society. The School of Architecture at Sheffield University (where Till was the director of architecture) is located in the Arts Tower, a 20-storey block that sits on a hill overlooking the city. The tower uses a Paternoster lift where open compartments move up and down in a continuous non-stop loop. Jeremy Till suggests that architecture is like the occupants of this building: removed from the life of the city in an ivory tower, constantly moving but going nowhere. I read this section of Architecture Depends while on a train to Sheffield to give a lecture in the Arts Tower. This is exactly the kind of bizarre coincidence between theory and the everyday that I imagine Jeremy Till would enjoy. His book contains a number of similar anecdotes running like a parallel narrative alongside the main, more academic, text. These stories, which are frequently amusing and often self-deprecating, highlight the discrepancy between architecture conceived as a perfect, timeless object by architects, and architecture as part of the messy reality of our lives as experienced by everyone else. This is Till’s central thesis: that architecture constantly resists its own dependency on the outside world. Buildings have lives beyond their designer’s control. Not only are they formed out of a mess of compromises (despite the supposed clarity of the RIBA Plan of Work), but they are also subject to constant change once built. They get lived in, added to, refurbished, neglected and sometimes demolished. Their official function – office, house, museum – is disturbed by an infinite number of smaller unofficial ones. People write on them, fall in love in them, break up outside them and ignore them. Till contends that architectural theory actively resists these contingencies, instead preferring to believe in various versions of the autonomy of architecture and the architect. My only criticism of this well written and entertaining book is that in order to discredit the figure of the autonomous architect, Jeremy Till has to make us believe in him in the first place. Much of the book is taken up with the construction of this straw man. Fragments of architectural theory from figures as diverse as Vitruvius, Le Corbusier, John Ruskin and Sigfried Gideon are lifted out of history and corralled into this enterprise. Yet I suspect these architectural myths are considerably less stable than Till allows. In a sense he is (over) stating a truism. Mies van der Rohe’s Barcelona Pavilion by may have been conceived as having little to do with the everyday, but that doesn’t stop it from being rained on. Buildings simply are part of the everyday whether architects like it or not. The question then becomes how different are they when this fact is foregrounded in the design process? The one concrete (well, straw) example Till offers here is ironically enough his own house. The self-commissioned private house is one where the architect has the greatest control and autonomy. The radical qualities of his own design, such as the straw-bale construction and “messy” planning, depend on exactly the kind of precise formal control that he admonishes architects for craving. If this is the everyday, then it is a highly refined version. If this is mess then it is artful dishevelment. A meta-theory of the everyday is an inherently risky business. In some ways it attempts to wrestle control back from all that contingency. So while this book hits most of its targets and successfully satirises the self-image of the architect, Architecture Depends depends itself on a model of architecture that is mostly wishful thinking.

|

Words Charles Holland |

|

|

||

|

Architecture Depends, by Jeremy Till, MIT Press, £16.95 |

||