|

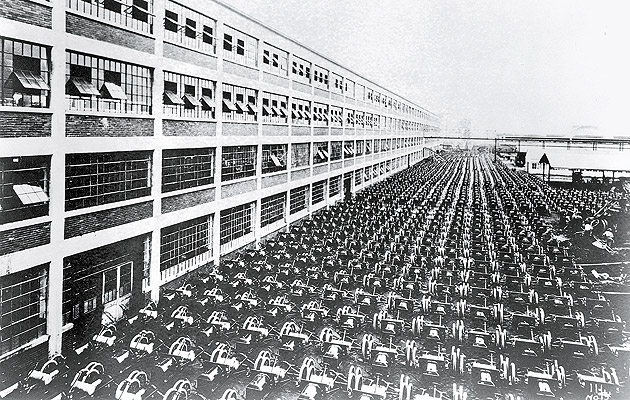

Highland Park plant and one day’s production of Model T’s (image: Henry Ford Museum) |

||

|

Will Wiles is fascinated by an engaging and rigorous history of the production line and how it speeded up the world Most people are, I think, dimly aware of the significance of the assembly line, without having too clear a conception of what it really is and what it means in practice. It is a confluence of technologies – more a management practice, a way of arranging and governing men and machines to achieve a particular result, than an invention in itself. That result is speed. The assembly line speeds manufacturing, it means more being made in less time by fewer hands. And the increase in speed, in productivity, wrought by the assembly line, was not slight: it was spectacular, and kept improving. It changed the economy, it changed society, it changed our cities and our food. It changed culture and war and work. America’s Assembly Line arrives on the centenary of the line, invented at the Ford company’s Highland Park motor works in Detroit. David Nye is the ideal man to tell the story. He is a historian of technology with an enviable knack for making potentially dry tales of economics, management and infrastructure gripping and memorable. His most recent book, When the Lights Went Out, was a history of power transmission in the US told through its failures, blackouts. This approach infused a far from naturally thrilling subject with drama and human interest. He has an easy command of the broad canvas and is generous with quotes. America’s Assembly Line is cogently organised and thoroughly compelling. Before the assembly line, manufacturing was still allied to craft – workers were skilled and able to perform several tasks. They operated in teams and worked on one job at a time. The assembly line inverted their world. Workers would now perform one specific task, and they would stay put while the work travelled between them, moving along the line. Parts were standardised, and each task was boiled down to its essentials. But the most important change was this: the pace was set by the line, not by the workers. Once it was fully implemented in 1913, the line made Ford unbeatable: he could make more cars than his competitors, sell them for less and pay his workers more. Wages were doubled to $5 a day – enough to afford the Model T Ford, which was cheaper than any pre-existing automobile. As well as increasing the volume of goods manufactured, the line increased the number of people able to afford them: a magical combination that offered a tantalising glimpse of universal, perpetual prosperity. Technocratic, managerial ideas become popular – civilisation was viewed as an immense edifice of thundering, unstoppable machinery, watched over by a governing caste of engineer-managers in white coats wielding clipboards and stopwatches, tended by faceless swarms of disposable workers. The cheerless motto of the 1933 “Century of Progress” exposition in Chicago was “Science Finds, Industry Applies, Man Conforms”. “Henry [Ford] has reduced the complexity of life to a definite number of jerks, twists and turns. Once a Ford employee has learned the special spasm expected from him, he can go through life without a single thought or emotion,” said one worker. “Assembly line production took decision-making away from workers and eliminated variety from their day,” writes Nye. Ford’s high wages were essential to combat high turnover. In the 1930s, the line was blamed for unemployment and embraced by totalitarian states; Yevgeny Zamyatin and Aldous Huxley turned mass-production into dystopian visions that resonate today. But it was then rehabilitated by becoming the beating heart of the Arsenal of Democracy, producing the aeroplanes that defeated Nazism and the consumer goods that defeated Sovietism. Then post-war Japan adopts the line, and Detroit is defeated. Alongside these stories, Nye also shows how the assembly line fed into culture over the decades, beginning with the hyperactive Jazz Age. “Chorus girls began to dance in synchronised lines, kicking and gesticulating in unison, each ‘girl’ appearing to be an interchangeable part of the line,” he writes. “Performers were recruited on the basis of uniform height and weight criteria, and were dressed identically … crowds paid to see showgirls express the logic of mass production as applied to the human body.” Charlie Chaplin and I Love Lucy, among others, exploit the “latently comic” side of the line: “assembly lines caused anxiety. A line can always be run faster, until human behaviour cannot be kept up. The machine always ‘wins’, and the humour lies in the individual’s attempts to conceal defeat as long as possible.”

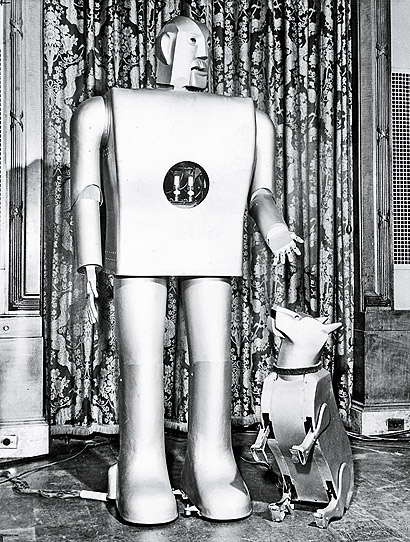

Elektro and Sparky, Westinghouse Robots, 1939 (image: Cleveland Public Library)

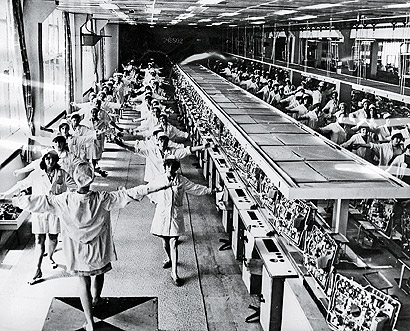

Workers exercising in a Soviet television plant, 1970 America’s Assembly Line, David E Nye, MIT Press, £20.95 |

Words Will Wiles |

|

|

||