|

|

||

|

Glenn Ligon offers an intriguing and personal history of black people in the US through their depiction on book covers, writes Sukhdev Sandhu The South Bronx in which artist Glenn Ligon (b.1960) grew up was a place of decline and unravelling. The Cross Bronx Expressway, designed by Robert Moses and completed in 1963, displaced thousands of residents. White flight, neglect of properties by landlords and economic stagnation combined to erode the civic infrastructures that had formerly sustained the area. By the 1970s, with arson widespread and drugs increasingly common, the Bronx was usually portrayed as a Brueghelian ghetto, a ghastly and extreme version of that bête noire of conservative politicians: the inner city. Ligon’s mother worked as a nurse’s aide at a local psychiatric hospital. Her salary was modest and she supported two children by herself. But she harboured ambitions for them and, when an Encyclopaedia Britannica salesman knocked on her door one day, she signed up for a complete set, even though it cost her a month’s rent. Ligon, already bookish and smart, went on to win a scholarship to a liberal private school. There he had his pick of 20th-century children’s classics – James and the Giant Peach, Charlotte’s Web, The Lion, The Witch and The Wardrobe – although, quickly perceiving these books were coded “white” and “middle class” by his Bronx contemporaries, he made a point of not talking about them too much.

Books – their words, images and symbolism – have featured prominently in much of Ligon’s art. He has produced paintings based on black-history colouring books from the 1970s, text paintings that feature lines from writers such as James Baldwin and Zora Neale Hurston, and works such as Notes on the Margin of the Black Book (1991–93) in which he installed homoerotic images of naked black men taken by Robert Mapplethorpe in two rows and between them inserted an array of provocative texts – by everyone from evangelists and activists to historians and curators – exploring the intersection of race and sex. A People on the Cover is part autobiography, part a demonstration of Ligon’s belief that “one could trace a history of black people in the United States simply by examining how we were represented on book covers”. While there has been plenty of scholarship and many gallery shows devoted to the role played by record sleeves in cementing and expanding black cultural politics, the bibliophile world is strikingly monocultural. Ligon begins with a section entitled “Beauty” that reproduces images of black writers such as LeRoi Jones, June Jordan, Gil Scott-Heron and Toni Morrison looking electrically earnest, in deep and defiant thought. What follows is “Synecdoche”, full of beautiful and arresting sequences of covers that feature specific body parts: singer Pearl Bailey’s The Raw Pearl shows a performer’s imploring hands, BA Botkin’s Lay My Burden Down is a history of slavery prefaced by a shot of an elderly fieldworker’s frail, leathery hands, and Nathan Wright Jr’s Ready To Riot sports a Black Power-esque fist.

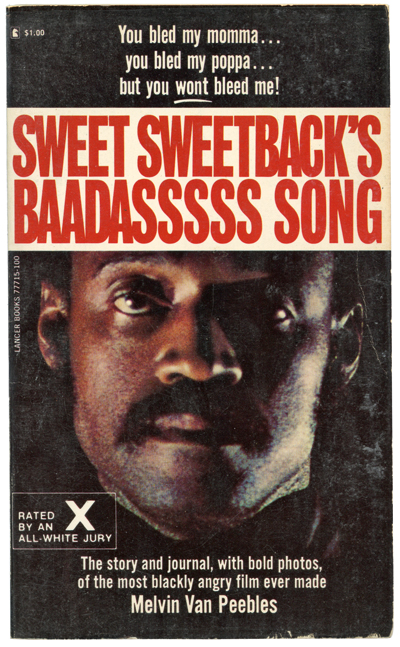

Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song by Melvin Van Peebles, 1971

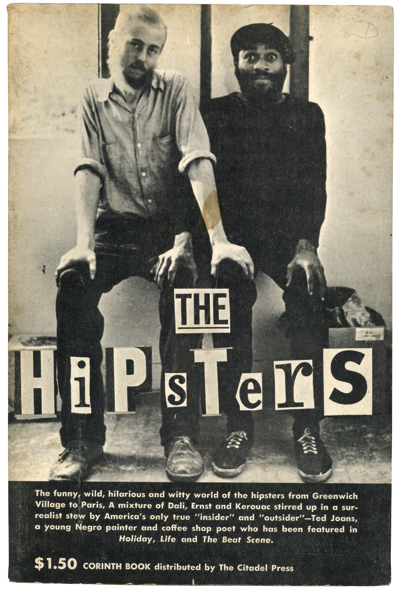

Left The Hipsters by Ted Joans, 1961 The most intriguing section is entitled “The Revolution Will Not Be Televised” and includes a quote from French playwright Jean Genet about how the real revolution in 1960s and 70s America “that was characterized by cultural and emotional exchanges between people of different races, was a quiet, less vocal one than that of the Panthers”. Accordingly, the pugilism and barricade bravura of Dick Gregory’s Nigger and Melvin Van Peebles’ Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song are followed by surrealist and jazz poet Ted Joans’s The Hipsters from 1961, the cover of which shows the “young Negro painter and coffee shop poet” with his hand on the thigh of a bearded white guy. The remaining two sections focus on the typographic dimensions of black book covers, and on titles that summon up the tantalising spectre of alternative Americas (among them Kodwo Eshun’s Afrofuturist bible More Brilliant Than The Sun and Suzan-Lori Parks’s The American Play, about a black gravedigger who resembles Abraham Lincoln). Other volumes will surely appear that talk to black authors about their choice of covers or that contain biographies of some of the cover artists themselves. But A People on the Cover (its own cover has no image!) is a gorgeous and sometimes moving book that is also a valuable account of Ligon’s sentimental and cultural education. |

Words Sukhdev Sandhu

A People on the Cover |

|

|

||