|

|

||

|

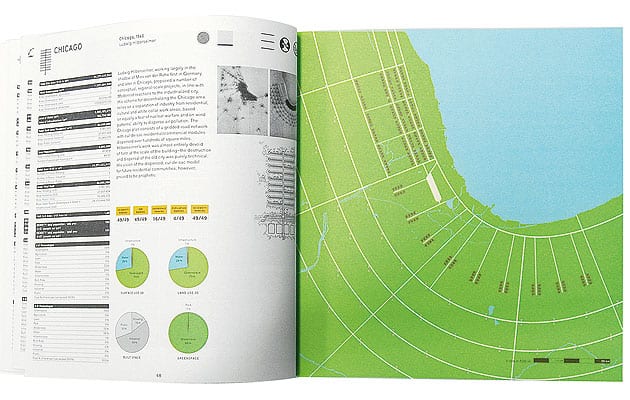

Ideal and utopian urban plans are condensed, measured and compared in this fascinating study. Will it help us map out our future, asks Sam Jacob. This book is a survey of 49 ideal, utopian and significant urban plans. Some of these cities are real, some imaginary, and they span from ancient Rome to sci-fi futures. They are projects that are familiar reference points in the ways that architects think about urbanism. As concepts, tactics, or formal solutions they represent a lexicon of urban planning. Developed by New York-based architect Work AC for an exhibition at the Storefront for Art and Architecture earlier this year, the examples are cut loose from their normal context, dislodged from their historical, theoretical or artistic significance and flattened into a logical, comparative system. The cities are set in the modern context of sustainable urbanism. To this end, the nature of the analysis is technical: data about population, density, land use and so on. The cities are then ranked like urban Top Trumps. Plans are redrawn in Illustrator-esque graphic style. The cover features beautiful silhouettes of the plans, which could be mysterious tribal tattoos or hieroglyphs from a lost language. This levelling of hierarchies does an amazing thing. It allows us to look afresh at familiar plans, as though the scales of assumption, received opinion and prejudice have fallen from our eyes. It echoes the tactic of suspended judgement that characterises Learning from Las Vegas and Rem Koolhaas’ research projects. The deadpan quality to the presentation also says “no rhetoric here!” as though the data is scientific rather than ideological. This has the advantage of sneaking what we might call the “culture” of urbanism – the cultural, sociological, or other aspects of urban planning – into the sustainability debate. This injection of the history of visionary, critical urbanism into the discourse on sustainability might be a way of reviving architectural rather than technocratic solutions to cities. By mimicking sustainability’s apparent lack of ideological programme, 49 Cities operates by stealth. However, partisan feeling is not far from the surface. Urban farming is presented here as unarguably good – not surprising from a firm best known for an urban farming pavilion at PS1 in 2008. Equally, the suburbs are described as “failed”. These views are by no means clear, and seem to undermine the project’s dispassionate research. Equally, one could endlessly debate the selection of subjects. Why do so few “real” cities make the cut? Where is Barcelona, that benchmark of any new masterplan promoting density and sustainability? In some cases, the research method seems as surreal as crash testing a Picasso – that is to say, is Cedric Price’s Fun Palace really a city? As research, this feels like the first part of a process and it is curious to imagine what might come next. It could extend further and deeper. Perhaps also at some point it will shake off its objectivity, step out of the shadows to argue a position. Equally this might be the start of a speculative project, in which case we would demand projection outwards from this data. Might a planner use this as a kind of pattern book to help guide decisions? What if the figures suggested by Paolo Soleri’s Mesa City coincidently chimed with policy in Milton Keynes and thus began the most unlikely of hybrids? Could you fuse disparate elements together to create, for example, floating-linear-garden Villes Radieuses? The question 49 Cities poses is suggestive: might non-judgemental reassessment of these projects allow us to recompose the language of urban planning outside of traditional partisan arguments? In doing this, we might forge solutions to present concerns which learn from histories real and fictional, ancient and modern. www.storefrontnews.org |

Words Sam Jacob |

|

|

||