|

Nestlé Chocolate Museum, Toluca, Mexico, Rojkind Arquitectos, 2007 |

||

|

The latest in Phaidon’s 10×10 series of critics’ choices provides a bookend to the boom years and hints at a more responsible future, says Justin McGuirk. Unlike Police Academy or Rocky, Phaidon’s 10×10 series of architecture books can happily clock up sequels with no danger of straining an implausible plot. In theory, at least, it’s an infallible formula: ten critics pick 100 emerging architects every five years or so, taking a snapshot of successive generations and the climates in which they operate. The first 10×10 came out in 2000, and I remember it well because it felt like an event. It was one of the early BIG books and came at a time when architecture was enjoying a sudden shot of glamour. Flush with the post-Bilbao glow, it was the newly visible manifestation of an economy going into overdrive. As such, its new companion, volume three, bookends a period that is now categorically over. Given the timing, it’s difficult not to look back over the past decade as a definable era: The Noughties, an age of opportunity. In fact, so much has changed since that first book, back when Foreign Office Architects was best known for a Belgo restaurant in Ladbroke Grove and digital renderings had the verisimilitude of Donkey Kong. We know by now what effects rampant economics, globalised practice and digital visualisation have wrought on architecture, but are these truisms apparent from one book to the other? Certainly, publishable architecture – the kind found in magazines and 10×10-style compilations – is a far more international phenomenon now than even ten years ago. Any practice that wasn’t European (that is, Dutch and Swiss), American or Japanese in the first book was an anomaly. Since then attention has started to shift away from these centres, with the rise of Chile, Mexico, Korea and China as design hothouses. Of course, architecture is a post-national preoccupation these days: practices commingle national blood as never before, incubated in international schools and multinational super-practices. The children of OMA continue to have a disproportionate influence, except this time FOA, MVRDV and Co have been replaced by JDS, BIG and Work AC (to name a few). By their early thirties some of these architects were building on a grander scale than any generation before them. They became masters of jetlag, fuelling emerging economies with ideas for new symbols. That is another essential byproduct of the Noughties. Architecture became marketing, and was thus conspicuously aware of itself as a brand. It’s amazing how prosaic many of the buildings in the first 10×10 seem now that we’ve gorged on the architectural imagination of the last decade. Back then, Miesian modernism was enjoying a resurgence made even stranger by the digital forms and datascapes published next to it. Those datascapes have since become a stylistic language, freed from theory and unleashed in the facets of Michel Rojkind’s Nestlé Chocolate Museum and countless other buildings these days. Architects were granted licence, at last, to decorate, to combine structure and ornament. These buildings were virtually predetermined entries in new magazines like icon or Mark. Markitecture would be a good term for them. That sounds critical – it is and it isn’t. As a collection of objects, these buildings are more prepossessing, more refined, than their predecessors a decade ago. Since this is a selective compendium, the more meretricious examples of Markitecture have been left out, and those are the ones we ought to be worrying about. However, what is interesting about 10×10/3 is how well it reflects the new mood. Given how suddenly the financial crisis hit architecture, you might expect this book to be a monument to recent libertarianism or a graveyard of visionary projects never to be completed. That is definitely not the case. To their credit, the critics (particularly the younger ones) have done justice to a new generation of architects who are not just interested in building objects. They include socially or politically minded interventionists like Teddy Cruz, International Festival, Raumlabor and Eyal Weizman. Some operate more as theorists and experimenters, such as Philippe Rahm, Keller Easterling and Aranda/Lasch. Then there’s Diébido Francis Kéré, who designs modest but wonderful schools in Burkina Faso. In the case of the first group, you could argue that the reaction to the age of plenty has been under way for some time, and that an alternative agenda is now tried, tested and ready to implement. This is the moment to bring people from the margins into the centre. Of course, one is reminded how subjective this selection – or any selection – is going to be. Each critic comes with a set of friends, tastes and allegiances. For instance, Andrew Mackenzie, who lives in Melbourne, picked his ten almost exclusively from Australia, which is refreshing but disproportionate. Ai Weiwei, understandably, leaned heavily towards the architects he picked for the Ordos 100 project. Bart Goldhoorn, who lives in Amsterdam and Moscow, selects from Amsterdam and Moscow. So it goes. There will never be a truly representative selection, and if we take that as read then 10×10/3 is an excellent almanac for the next few years or so. 10×10/3, Phaidon, £49.95

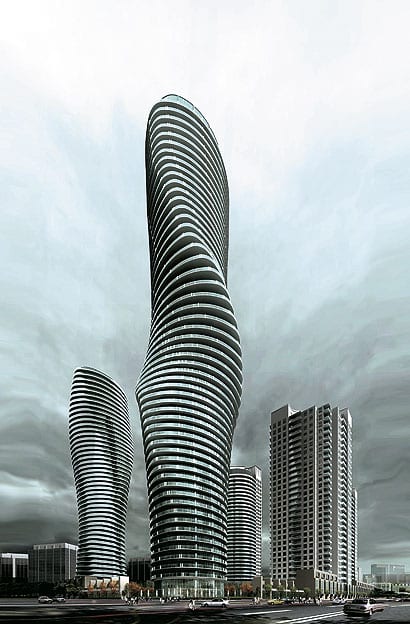

Absolute Towers, Mississauga, Canada by MAD Office, 2009

Junya Ishigami’s Yohji Yamamoto Flagship store, New York, USA |

Words Justin McGuirk |

|

|

||

|

The book which is covered in plastic mesh |

||