Working in rainbow-bright colours and bold patterns, Yinka Ilori puts a welcome face on public spaces, giving the city back its sense of fun

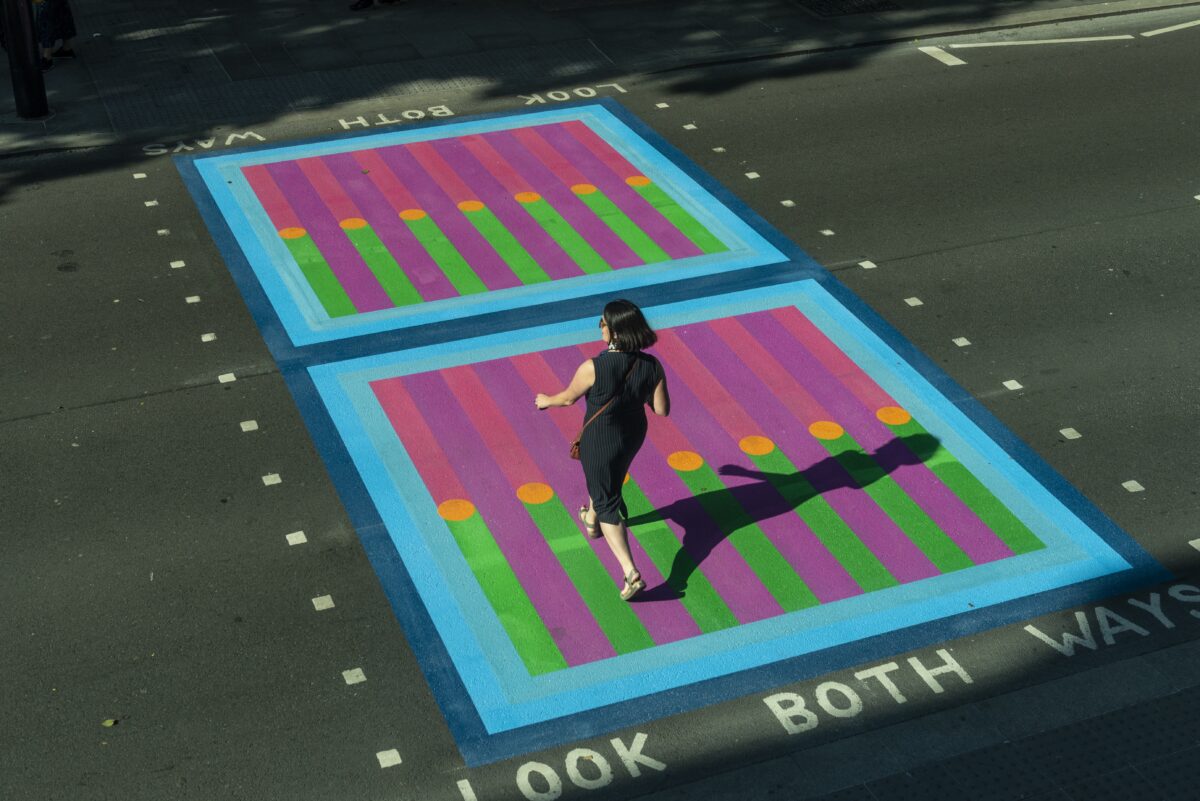

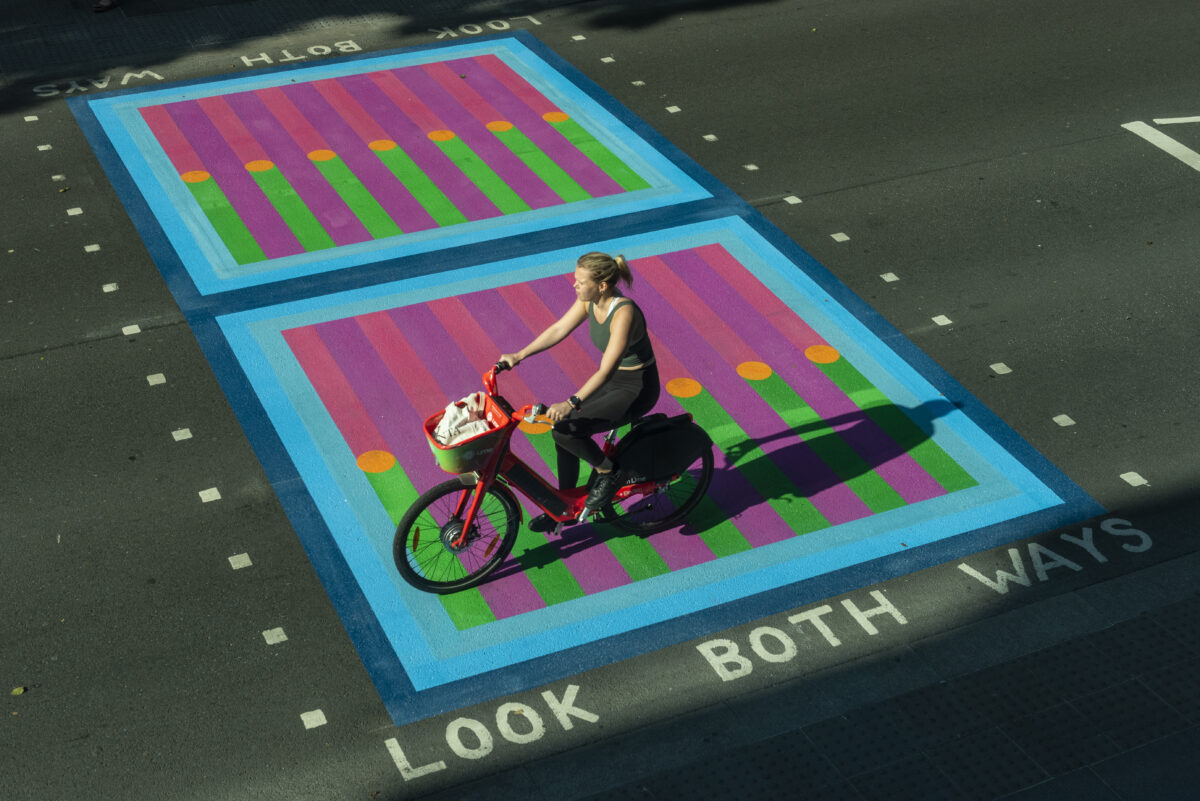

Photography courtesy of Yinka Ilori. London Design Festival Landmark Project ‘Bring London Together’, 2021

Photography courtesy of Yinka Ilori. London Design Festival Landmark Project ‘Bring London Together’, 2021

Words by Riya Patel

When an ice cream van passes his north London studio, Yinka Ilori stops mid-conversation to hear its jolly tune. It arrives just as the young British designer is explaining how his public artworks are all about bringing moments of delight to this sometimes grim city – through murals, streetscapes, playgrounds and pop-ups.

In just 12 years, Ilori has gone from design graduate to MBE, celebrated in 2021 for the contribution his large-scale, colourful works have made to public life. That heady rise has seen the designer create installations for Somerset House and Dulwich Picture Gallery, for developments at Canary Wharf and Greenwich Peninsula, and for the overlooked fringes of the capital, too.

Themes drawn from his own experience of family life growing up in inner-city London play out in all of these works: from projects to improve local communities to high-profile collaborations.

Photography by Lewis Khan

Photography by Lewis Khan

Ilori graduated in furniture design from London Metropolitan University in 2009, and his knack for handling bold pattern and colour first showed itself in a self-initiated collection of reinvigorated street chairs – painted and reupholstered with features of the traditional Nigerian dress his parents proudly wore.

Graphics found in the popular fabrics he was surrounded by growing up, such as Swiss voile and Dutch wax print, would go on to become part of his design DNA. He set up his own studio in 2017, re-focusing from furniture to installations after becoming dissatisfied with the exhibition environment.

He says: ‘I’ve always loved community, working with people and interaction with my work, because that is more rewarding to me.’ Ilori’s colours continued to be characteristically bright, but the patterns became increasingly abstracted to account for their urban scale. Combinations of geometric shapes are often set in bands like the layers of a cake.

Photography featuring Creative Courts by Yinka Ilori

Photography featuring Creative Courts by Yinka Ilori

Segments of intersecting lilac, yellow, sky blue, green, inky purple and red form an aesthetic that is distinctively Ilori’s, but manages not to be restrictive or repetitive. ‘All the work I do has a personal element, even if it’s a public space,’ he says. ‘The colour palettes remind me of my parents being joyful. I think about how I can continue their legacy of joy in my work. And how to reflect the people who the spaces are meant for.’

Happy Street in Battersea was Ilori’s first work in the public realm. The transformation of an overlooked railway underpass is a permanent work designed for Wandsworth Council in collaboration with the local community for London Festival of Architecture 2019. The glum space was enveloped with colour, with rainbow stripes on the underside of the bridge and 56 enamel panels lining the sides of the underpass.

The concept was developed over a month of workshops on colour theory involving Ilori, local residents and school children. ‘There’s huge development going on in Battersea, with houses worth millions being built next to council estates,’ he says. ‘Happy Street is something for local people to be proud of, so they don’t feel left out of the conversation. That happens a lot in public spaces.’

Photography by Lewis Khan featuring Yinka Ilori’s studio

Photography by Lewis Khan featuring Yinka Ilori’s studio

Giving communities agency in the built environment is a key function of Ilori’s public works. Happy Street was completed ahead of a moment of great reckoning over how our public spaces have been shaped. After anti-racism protestors pulled down a statue of 17th-century slave trader Edward Colston in Bristol in 2020, the Mayor of London established a commission for diversity in the public realm.

Its remit is to review statues, plaques and street names, making them more representative of the capital’s racial, social and economic mix. Ilori’s work is not overtly political, but the capability of public spaces and institutions to exclude is never far from his mind. The first time his parents had ever been to a gallery or museum was for the opening of The Colour Palace at Dulwich Picture Gallery in 2019.

A collaboration between Ilori and architects Pricegore, it was a 10m-high, cube-shaped viewing structure that clashed references to the architecture of Soane’s gallery and the busy fabric markets of Lagos. Estate Playground for CitizenM hotel in 2017 – a representation of Ilori’s childhood playground on a council housing estate – was also an invitation for a wider audience to feel welcome.

Photography by Lewis Khan featuring Yinka Ilori’s studio

Photography by Lewis Khan featuring Yinka Ilori’s studio

‘People don’t always go to galleries because they feel like they don’t belong, so how do I change that with my works? Make them feel like they can go to this hotel or museum and tell their friends to come here too? I can do it by making something everyone can connect with.’

When the coronavirus pandemic forced the closure of traditional art spaces, it gave Ilori further impetus to bring his work to the streets. A billboard campaign with creative agency Jack Arts was conceived to spread messages of hope and positivity. If You Can Dream Then Anything is Possible saw Ilori’s popular appeal spread to the whole of the UK, and beyond the architecture and design community.

A three-section billboard with the words Better Days Are Coming I Promise was made for the Chelsea and Westminster Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, to highlight the heroic efforts of hospital staff in the pandemic. Painted murals for Harrow Council (Love Always Wins) and British Red Cross (This is Human Kind) gave the designer license to become more lyrical but also playful with graphic motifs – flowers, ice-cream cones and rainbows frame words rendered in a retro-looking, puffy typeface.

Photography courtesy of Yinka Ilori. London Design Festival Landmark Project ‘Bring London Together’, 2021

Photography courtesy of Yinka Ilori. London Design Festival Landmark Project ‘Bring London Together’, 2021

The success of these works led to a landmark project for the London Design Festival in 2021 called Bring London Together. Site-specific patterns were applied to pedestrian crossings along Tottenham Court Road, referencing the architecture, history and activity of the major London street. Festive patterns brought a celebratory spirit back to the street, where shops, theatres and restaurants had long stood empty over the pandemic.

Ilori’s sunny outlook, expressed in these murals and streetscapes, hit the right mood at a desperate time for many, leading to surprise requests for prints and artwork for people’s homes. ‘People think I’m a graphic designer. I’m not, but graphics are normal to me,’ he says. Like his parents’ traditional Nigerian dress, he says: ‘There’s an element of my work that loves being loud and being seen and being different and being spoken about.’

Now his family culture is part of London’s fabric, too. So how does he feel seeing motifs from his personal life writ large in the urban environment? His answer reveals that there is much more to the works than mere surface treatment.

Photography by Mark Cocksedge featuring LEGO and Yinka Ilori’s Laundrette of Dreams

Photography by Mark Cocksedge featuring LEGO and Yinka Ilori’s Laundrette of Dreams

‘I love telling a story through layers. Patterns in Nigerian culture can communicate marital status or wealth. In my work, they might talk about love, hope, identity or sexuality. Storytelling allows me to choose which parts [of my life] to share, or to hide within an artwork like a secret between us.’

In 2021, a collaboration with Lego brought Ilori back to working on a community project, Launderette of Dreams on Bethnal Green Road in east London. The laundrette theme for this pop-up play space was inspired by the one Ilori and his siblings would happily visit as a child.

‘We got an hour to spend with no parents around, just fun and chaos,’ he says. ‘The project was about how we could use these mundane spaces to dream and be creative.’

Photography by Mark Cocksedge featuring LEGO and Yinka Ilori’s Laundrette of Dreams

Photography by Mark Cocksedge featuring LEGO and Yinka Ilori’s Laundrette of Dreams

The launderette is also a common fixture of inner-London neighbourhoods, throwing together local people from different walks of life and opening up dialogues between them. Ilori asked children from his former primary school to work with him on re-imagining the space.

Over 200,000 Lego bricks were used to create a toy vending machine, an everchanging mural, a hopscotch floor and interactive washing machines. Play is clearly a preoccupation for Ilori.

Like a Peter Pan of the art and design world, his fantastical works transport both children and adults beyond the limitations of what is expected of them. Fun is the mechanism for transcending class boundaries and creating environments that welcome all. The Launderette of Dreams opened when social mixing was finally allowed after months of disrupted schooling and restricted play opportunities over the pandemic.

Photography by Lewis Khan featuring Yinka Ilori’s studio

Photography by Lewis Khan featuring Yinka Ilori’s studio

As worries mount about the long-term effect of the pandemic on children’s health and development – and the stark difference between those from different social and economic backgrounds – the launderette is a comforting reminder that creativity can be encouraged in every circumstance.

‘I grew up in an environment like this, and I know the importance of these projects in terms of access to art and design. I didn’t get the chance to go to museums and galleries as a kid, I didn’t think [design] was something I would do,’ Ilori says. ‘[The launderette] opened parents’ minds, helped them realise that their kids playing with Lego could actually lead to something.’

Listening to Joy, an installation at the V&A Dundee, presents the next evolution of playful thinking in Ilori’s work. Visitors make their way through a colourful maze via zipped-mesh walls that change their routes through the space. Two circular xylophones add a further interactive element, and the resulting soundscape of music, laughter and movement is recorded as a performance piece – again showing Ilori’s conscience that everyone’s presence in the space matters.

Photography by Michael McGurk featuring Listening to Joy at V&A Dundee, 2021

Photography by Michael McGurk featuring Listening to Joy at V&A Dundee, 2021

Sound is also a feature of Ilori’s forthcoming installation with artist Peter Adjaye, a permanent public artwork at Kings Hill in Kent, commissioned by Turner Contemporary and inspired by the species of apples native to the area. As well as exploring sound, Ilori will work with light at Liverpool’s River of Light festival this summer. The move into different media is partly a result of his frustration with his reputation as an artist that works only with colour.

Embracing it at scale is not easy, as is evidenced by the many architects wanting to partner with Ilori, but he nevertheless wants to show there are more strings to his bow. The world beyond London is now calling for collaborations, thanks to his rapid success and the continuing appeal of his work. The next phase for his studio is to build a legacy that is sustainable, and to choose projects where Ilori can remain in personal control of the output.

Staying grounded is important, but the dreaming will never stop. A flamingo-themed playground for east London’s Becontree Estate is the latest vehicle in the designer’s mission to bring the world more reverie. ‘My installations always make you feel like you are somewhere else,’ he says. ‘I find it satisfying to see people’s reaction to my work, see them smile or have a moment of joy.’

Get a curated collection of design and architecture news in your inbox by signing up to our ICON Weekly newsletter