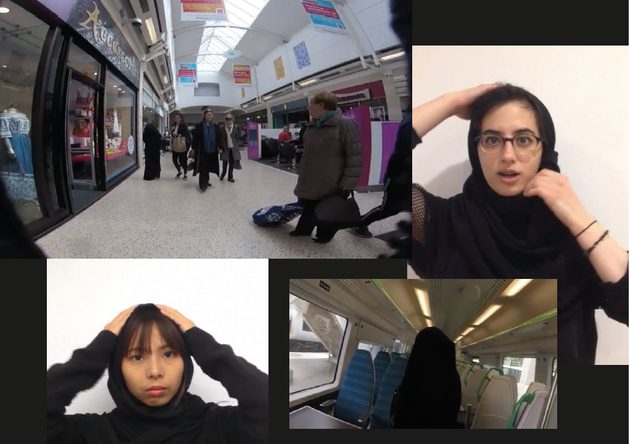

Stills from Walk a Mile in Her Veil and Snapchat Me That Crisis (both 2016). Courtesy Yasmeen Sabri

Stills from Walk a Mile in Her Veil and Snapchat Me That Crisis (both 2016). Courtesy Yasmeen Sabri

Royal College of Art-trained designer-slash-artist Yasmeen Sabri has been creating a ‘fuck you to the white cube’, writes Debika Ray

‘When I was studying fine art, my work started naturally evolving off the canvas,’ Yasmeen Sabri says, referring to her time as an undergraduate at London’s Central Saint Martins. As she gives a tour of her studio – a large, cool basement space and courtyard in the Jordanian capital, Amman – she gesticulates at her artworks, which are made of materials you would find on construction sites or in DIY stores, such as emulsion paint, foam board, cling film, barbed wire, plants, industrial lighting. The works, she explains, explore subjects such as gender politics and the destruction of culture in her region, and she has exhibited them at institutions like Darat al Funun, the city’s revered museum of contemporary Arabic art.

Her move towards design-oriented projects began while she was studying information experience design at the Royal College of Art. It’s a journey that reflects a wider blurring of boundaries in the creative sector between art and design, experience and object, communication and contemplation. Today, temporary installations are as much a part of design fairs as permanent work, ranging from thoughtful propositions that temporarily change the way we interact with each other and the urban context, to eye-catching displays that act as marketing tools for brands or sponsors.

For Sabri, this shift stemmed from a desire to make more explicit interventions about the politics of the world around her. For example, Walk a Mile in Her Veil (2016) is an exploration of the turbulent discourse that surrounds a specific item of women’s clothing: the burkha. ‘It was an in-depth study of why women choose it – whether for financial reasons, social reasons, for work or culture, and the different styles [in which it is worn].’ Sabri strode through the streets of London wearing one and filming how people reacted to her, then presented the results at her RCA degree show, alongside veils for visitors to try on.

Designer-slash-artist Yasmeen Sabri. Photography courtesy Yasmeen Sabri

Designer-slash-artist Yasmeen Sabri. Photography courtesy Yasmeen Sabri

Displayed shortly after the Brexit referendum, this work elicited a shocking response. One attendee attempted to destroy the display and told Sabri to ‘go back to Saudi Arabia’ before being escorted out. She went on to show the work at London’s Somerset House and the Offenes Kulturhaus in Linz, Austria. Another work, Snapchat Me That Crisis (2016), is a short film about the refugee crisis. Sabri released it in various lengths on five different social media platforms to show how such modes of communication can degrade public discourse. ‘How can you ever express yourself through an eight-second video, or learn anything when you’re bombarded with so much information?’ she asks.

In producing works that confront and disrupt, she also wanted to challenge the ‘look but don’t touch’ axiom often present in more traditional exhibition settings and in the pristine world of fine art – a ‘fuck you to the white cube’, she says. An example of this is Network of Swings (2017), her most ambitious work to date, and one that combines all the facets of design that interest her: construction, urbanism, political commentary, public engagement and digital communication.

The starting point was the makeshift wooden swings made from repurposed materials that are erected across Jordan during Eid. Intrigued by the capacity for a self-built temporary installation to bring people together for merrymaking and celebration, and noting the lack of public space in the country, Sabri built three swing sets. One was displayed as part of an exhibition at Amman Design Week in 2017. In a context that is by its very nature somewhat rarefied, Sabri took pleasure in watching visitors realising they could touch and play with the work, then stepping on to the platform to use it.

The others were built at Jabal Al Natheef, a deprived neighbourhood in Amman, and in the Zaatari refugee camp on the Syrian border, home to almost 80,000 people. Then she created an Instagram account to connect the swings, digitally merging three locations and offering them to the public to comment on and enjoy. Finally, she printed a flyer to instruct others on how to build their own swing sets, and join the network.

The purpose, says Sabri, was to connect disparate groups and the wider world in a moment of lightness and communality. ‘Play is an international language and because of the nature of our social, economic and political problems, people forget to play,’ she says. ‘I wanted everyone to take a minute and play together, regardless of gender, social class, religion or background.’

One of her swings went on display at the Jordan Children’s Museum in August. Even when placing it in a formal institutional setting, Sabri continues to look beyond the usual audience for design – and certainly past the white cube.

%MCEPASTEBIN%