|

Apple Watch |

||

|

The Apple Watch is the latest wearable internet technology with the capability to monitor the user’s heart rate and activity levels. As our bodies dissolve further into the network, are these devices just tracking our health or do they herald something darker? Tim Cook, Apple’s chief executive, is smiling and clapping like everyone else. The room is enraptured. Heartbeats raised, skin prickling in an ecstatic devotion for this moment of revelation. Everyone is glossy, as though the excitement within them is generating an electrostatic glow. Around the world thousands of tiny electronic pulses record and respond to Cook’s words. Data packets flowing through the nervous system of the internet. Biology, technology and electricity combined in one crackling moment of collective connection. He, they (and we) are welcoming into the world the long-anticipated Apple Watch, the company’s first piece of wearable tech. The language Cook uses promises smoothness, integration, monitoring and connectivity. And deep in our digital psyche these ideas stir us. Yes please, we say, faster, deeper, more. That’s why everyone’s clapping. Not only for the thing itself but for the idea that it represents.

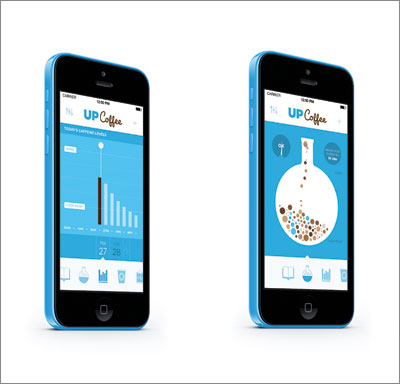

Jawbone UP fitness tracker This is an idea that has already been sketched out by the trackers and smart watches that have defined wearables up to now: the Samsung Gear, the Jawbone UP, various Fitbits, the Nike+ FuelBand and so on. All these devices promise to connect your physical activity to the digital. They gather information by monitoring your movements and pass this to your phone, which in turn uploads it to servers where the data is processed. Then data flows back to you, feedback, messages of encouragement, stats on how far you walked, how vigorous your activity has been, how many flights of steps you climbed, calories burnt. Along with phone-based fitness apps such as Nike+ and Strava, your entire daily performance – diet, sleep patterns, movements – can now be logged by combinations of motion sensors, accelerometers and GPS chips. Every action generates a record, building up an archive that maps your lifestyle and, often, your fitness regime. The logic of all this self-metrification, all this data gathering, is to improve yourself. It’s behavioural science strapped to your wrist. These devices help you to set goals, nudge you towards completing them, remind you, and reward you with a bewildering amount of virtual medals and cups, so even the feeblest of effort can fill your virtual trophy cabinet.

Nike+ FuelBand Soon though, you’re hooked – competing with your personal best, with friends you’ve linked to, with strangers who might run the same routes. And this is the idea: that the constant digital monitoring and feedback pushes you towards a better version of yourself. But it’s a form of better that is, in its own way, pure ideology. It’s an idea of lifestyle defined not just by healthy living (which is its own ideology) but also by marketing. As soon as you strap the tracker on, you’re hard-wired (or at least bluetooth-tethered) to a corporate image of humanity, to an (often) West Coast idea of living. Our newly metricised existences are ones in which big data intersects with ordinary life, always updated, continuously cross-referenced. But as much as they may aim to change us, trackers have another purpose. As we welcome them in to the privacy of our own lives, we grant access to data that would not have previously been available. As our data is shared, it becomes a resource for other kinds of study. The data collected by Jawbone from UP users, for example, is sliced and diced by its data science team. They have mapped the South Napa Earthquake, the strongest in Northern California for 25 years, through the sleep patterns of its users. We could think of this as suggesting how diffuse personal technology transforms us into information-gathering nodes: people as seismographs. The data is sociological too. Jawbone’s wonks have looked at global patterns of sleep through the company’s user-generated data. Tokyo apparently is worst off, with an average of five hours 44 minutes, while the longest sleepers are in Melbourne (six hours 58 minutes). Or bedtime – the latest is in Moscow at 12:46am, the earliest in Brisbane at 10:57pm. Or steps taken per day – the most by the citizens of Stockholm (8,876), the least in São Paulo (6,254).

These may just be curiosities but they begin to point to how the indexing of the individual opens up new ways of understanding lifestyle, culture and much more. Just as trackers hope to nudge individual behaviour, perhaps too the big data sets will start to reform our habitats as well as our habits. These forms of data are already finding ways in the wider systems of politics and economics. In 2013, BP America provided 14,000 employees, 4,000 retirees and 6,000 spouses with Fitbit trackers. The scheme allowed the company to monitor its employees’ lifestyles. And in turn share this information with its health insurance provider. The shift from integrating trackers into corporate “wellness” programmes towards sharing the data with healthcare providers will impact on what health and healthcare might actually be. Modelled on America’s strange and brutal health system, all this digitisation suggests an entirely consumerised provision of care.

Fitbit health tracker Equally, the idea of the patient as an active partner in their own health may sound sensible, but we can guess that behind every carrot (juice) dangled in front of us is an equally substantial stick. In other words, are we willingly strapping on electronic tags, devices that police our behaviour and penalise us for any deviation? The future of wearable technology is hinted at when Cook, in his keynote presentation, says you can barely tell where the software stops and the hardware begins. I think he means more than that. Cook might wax lyrical about Apple‘s seamless industrial design merging the digital and the physical. But wearable technology goes further. Styled as watches and bracelets, they are everyday objects rather than specialist tech devices. They begin to merge the digital world with that of fashion, clothes, jewellery, of hundreds of years of relationship between humans and their things. And, as Apple CEOs like to say, one more thing: they begin to dissolve the boundary between our own bodies and the network.

iPhone 6 and iPhone 6 Plus The dream of wearability is the diffusion of digital culture into the fabric of everyday life. Allied to the ever-impending Internet of Things – a universe of always-connected things endlessly updating their status – it’s a vision of society that maps the basic diagram of the internet into the whole world. Machine sentience everywhere, everything linked in – what the techno-optimists argue is a virtuous circle of data connectivity. We already, if we so choose, generate vast quantities of personal data. From credit scores to location data, from our reading speed to our networks of friends and families. From the smart city to the inner workings of our biology, the flows of capital, goods, even the own blood within our veins can now be routed in an ecstasy of monitoring. It is an algorithmic utopia of ever increasing efficiency, speed, health and smoothness.

Samsung Gear S smart watch Everything talking to everything else. And above this silent machine chatter, our own selves steered by mild prompts from our kindly devices. This then is the dream. Your data-enabled shoes talk to your home’s heating system which adjusts according to walking speed, dampness of pavement and so on. Your heart rate alerts your fridge to your likely snack demands; this in turn communicates with a supermarket delivery system. All of this is mitigated against the social sentiments expressed on your Facebook feed, which alerts your doctor if, say, your intake of Ben & Jerry’s is on the rise. Consumerism, mood, motion and biometrics all blended seamlessly into one. Much more than simply a route to a functioning cardiovascular system and a trim waistline, trackers and their ilk are about inventing a new idea of what it means to have a human body in the 21st century. They embed an idea – an ideology even – about lifestyle and behaviour within our own corporeal self. They are moral devices, whose unstated narratives are those of health and youth, the blissful states of energy, freedom, self-reliance and self-fulfilment. In place of more traditional (and explicit) ideologies of politics or religion, we now bury within sci-fi matt-rubber bracelets or stainless steel and sapphire crystal more invisible values: the Californian Ideology plugged right into our own physiology. This article was first published in Icon’s November 2014 issue: Sport, under the headline “Every move you make”. Buy back issues or subscribe to the magazine for more like this. In his DM25 talk at the Design Museum, in association with Icon, Jonathan Ive discussed the development of the Apple Watch |

Words Sam Jacob

Images: Jawbone; Justin Sullivan/Getty Images; FitBit; Samsung; Nike |

|

|

||

Apple chief executive Tim Cook launches the Apple Watch in September 2014