Vorticism was a short-lived radical art movement in Britain that celebrated urbanity and the age of the machine.

Vorticism was a British avant-garde group formed in London in 1914 with the aim of creating art that captured the energy of the modern world. Vorticists were known to be England’s first avant-garde artisitc movement. The movement’s artists and writers praised machine-made products and celebrated urbanism, and flourished very briefly in England.

The movement was formed by artist and writer Wyndham Lewis in 1914, and was partially inspired by the Cubism of continental Europe. It also shared some characteristics with Futurism, though Lewis himself condemned of the Futurists and insisted that Vorticism offered an alternative vision.

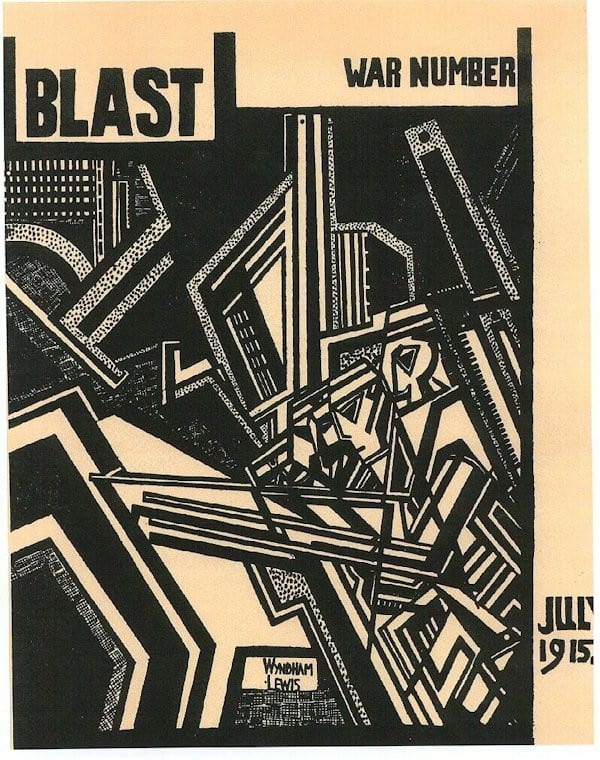

Vorticist art was defined by bold colours, harsh lines and sharp angles, and pivoted around a fascination with the age of the machine. The style of the art produced was geometric, close to abstract in form, and like the Cubists presented reality as fragmented.

The name was given to the group by one of its members, the American poet Ezra Pound. Lewis explained that the name was inspired by the idea of looking into the centre of a whirlpool – the vortex – where the energy was most concentrated.

The movement began when Lewis founded the Rebel Art Centre as a meeting place for artists in March 1914, London. He wanted the centre to be an experimental space where artists could discuss their ideas. It closed after a few months due to intenral disputes.

Lewis published a confrontational manifesto in the movement’s magazine Blast, where he criticised the decadence of British art and culture and advocated for an aesthetic that would more accurately reflect the present day. ‘The New Vortex,’ he wrote, ‘plunges to the heart of the Present – we produce a New Living Abstraction’.

Blast outlined the Vorticist rejection of British traditions, moving away from traditional rural landscapes and nudes in favour of innovation and urbanisation. The magazine’s design epitmised this modernity. Its cover was bright pink, and featured nothing but its name written in bold and diagonally orientated.

Only two editions of the magazine were published, the first in June 1914 just before the First World War broke out. The second, more solemn issue, subtitled ‘War Number,’ was published in July 1915. After its release, the first Vorticist exhibition was held in June 1915 in the Dore Gallery, London.

Other artists involved with the group were the paitnings Lawrence Atkinson, Cuthbert Hamilton, William Roberts, Edward Wadsworth, and the sculptors Sir Jacob Epstein and Henri Gaudier-Brzeska. Vorticism was one of the few avant-garde movements from the early 20th century that included women artists, among them Jessica Dismorr and Helen Saunders.

The first world war brought Vorticism to a premature end. Many of its artists were drafted to the frontlines, and several killed in action. Afterwards, Lewis attempted to revive it with Group X, but in Britain the terrible experiences of war brought a rejection of the avant-guard in favour of ‘the Return to Order,’ a revival of conservative art.

After years of neglect, a retrospective exhibition was held at the Tate Gallery in 1956, named Wyndham Lewis and Vorticism. The placing of Lewis alone at the apex of the movement angered other artists who had been involved and felt under-represented.

Though Voritcism was brief, it has been recognised as important for its contribution to modernism in Britain. More recent exhibitions, such as The Vorticists: Manifesto for the Modern World at Tate Britain in 2011, has done much place it in context, and establish the Vorticists’ position as harbringers of a modern aesthetic across media.