|

|

||

|

The ‘Kagan look’ took mid-century modern design and added organic forms, a sense of joy – and even comfort. No wonder he is so often overlooked, says John Jervis Vladimir Kagan is not what today’s prim cultists expect of mid-century modern design. Not for Kagan mean layers of plywood on spindly steel legs: his furniture rejoices in rich walnut, deep upholstery and sensuous shape, but also, most importantly, in space. His quantity and invention could be overwhelming, and thus his quality variable, but Kagan’s ability to balance taut structure with generous form was unrivalled. Kagan, who died last year, wasn’t some doctrinaire modernist hired by brands to design new chairs via an endless process of refinement. Kagan was the brand, and he needed to work fast. The son of a successful Jewish cabinetmaker who had fled Germany in 1938, Kagan produced designs for the family workshop in Manhattan from his teens while studying architecture at Columbia at night – one of his signature pieces, the encircling Barrel chair of 1947, was created when he was just 20. His knowledge of craftsmanship was key, exemplified by intricate detailing and complex upholstery, but also by his grasp of the possibilities and limitations of traditional materials when put to avant-garde purposes. Early work drew on his father’s Bauhaus interests and on folk art, incorporating tiles by Russian and Dutch artists, repoussé work and linen-fold details. But he swiftly embraced technology: stylish cocktail bars hid radios and TVs behind sliding tambour doors.

Kagan’s Ondine chair (1958) in leather on a walnut base The family workshop gave him freedom to experiment, leading to the increasingly expressive forms that encapsulated the Kagan look in the 1950s. His famous ‘tri-symmetric’ legs for chairs, chaise longues and coffee tables, based on studies of tree roots, have a graceful sculptural presence that brings Isamu Noguchi to mind. Yet, thanks to Kagan’s knowledge of upholstery and anatomy, his biomorphic furniture offered the comfort that industrial designers often eschewed. Kagan, just as ardent in his belief that form followed function, created modern design you could actually sit on. His 57th Street showroom became the go-to place for wealthy clients: Marilyn Monroe, Gary Cooper, Frank Sinatra and Andy Warhol all went Kagan. His sofas were iconic, particular the armless Serpentine, a bulbous three-and-a-half metre apostrophe designed to sit in the centre of the room. He explored alternative materials, from polyurethane to wrought iron, but it was his experiments with PlexiGlas in the 1960s that stuck. Thick slabs were used for desks or daybeds, and gave an eye-catching floating base to his modular, multilevel Omnibus sofa, an unusually angular affair that successfully updated the Kagan brand. High-profile interior commissions followed, both corporate and domestic, with rotating conversation pits or bespoke desks with built-in computers. He experimented with portable furniture to suit itinerant lifestyles and created outlandish, high-tech ‘houses of the future’ for Monsanto at Disneyland and General Electric at the 1967 World’s Fair. Yet Kagan never found fashion in Europe, despite brushing against post-modernism in the 1970s. He considered Italian modernism overly ornate, and Memphis as hype (a mistake, he later admitted). He admired Finn Juhl and Hans Wegner deeply, but when he proposed manufacturing in Denmark in the 1950s, his work proved too intricate to replicate.

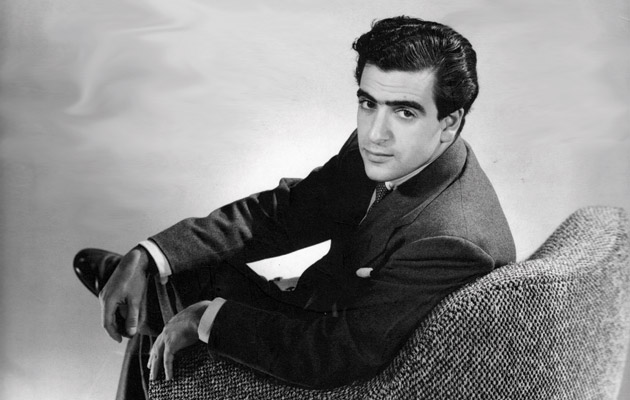

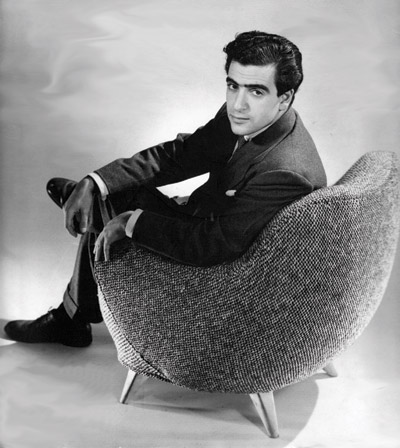

Kagan sitting on his Barrel chair (1947) in the early 1950s And criticism from cognoscenti that his furniture had more in common with fashion than design hurt. He tried paring back, for instance with the Japanese simplicity of his Cubist dining chair, but found this invited copyists that a small firm could ill afford. In reality, however, Kagan had identified a vigorous alternative market that recoiled from the dominance of industrial purity at exorbitant price tags. Walking round the mid-century displays at the Pinakothek der Moderne in Munich last month, I was hit by an overwhelming sense of tedium – the inclusion of just one of Kagan’s pieces in place of yet another lifeless shelving system would have improved things infinitely. As a latterday friend and ally, Zaha Hadid, who died one week before him, wrote: ‘While the works of his contemporaries are definitive, finite and frozen, you experience a wonderful sense of liberation in the nonlinear, organic forms of Vladimir’s collections.’ Amen to that. |

Words John Jervis |

|

|

||