For the Off-White founder, everything creative was political. Here we publish our interview with the late design polymath from Spring 2021

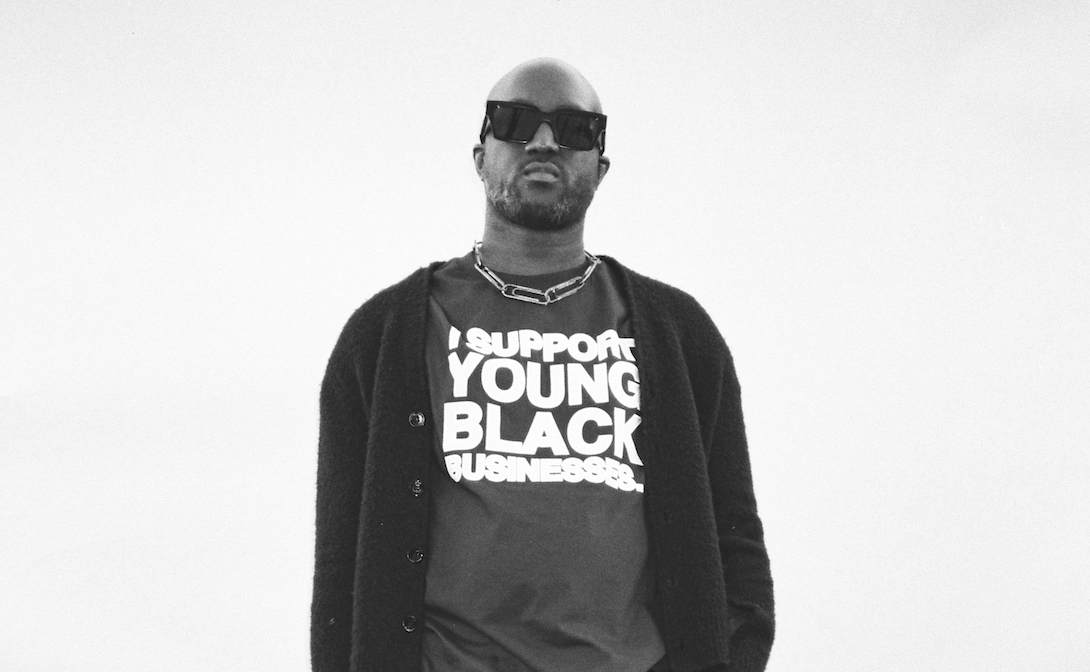

Abloh wearing his brand’s ‘I Support Young Black Businesses’ T-shirt. Photograph: Alessio Segala

Abloh wearing his brand’s ‘I Support Young Black Businesses’ T-shirt. Photograph: Alessio Segala

Words by Flo Wales Bonner

This is an archival piece from Spring 2021

More often than not, when preparing to interview a significant cultural figure, one is sent a semi-apologetic email beforehand from a PR representative, asking that the questions be sent in advance (occasionally even accompanied by a list of no-go topics). I receive no such request ahead of speaking to Virgil Abloh. This surprises me, but perhaps it shouldn’t – this is, after all, a man whose practice revolves around self-expression on a very public scale.

Self-expression that enjoys multiple outlets, given that 40-year-old Abloh is the epitome of the contemporary polymath – a figure with fingers in so many pies, whether it’s running his cultish fashion label Off-White, helming the menswear collections at Louis Vuitton, collaborating on art and design projects with companies as diverse as IKEA, Mercedes-Benz and Nike, having a mid-career retrospective at Chicago’s Museum of Contemporary Art or moonlighting as a DJ – all the while maintaining a social media following of more than six million.

Figures of Speech, Abloh’s solo show at Chicago’s Museum of Contemporary Art in 2019. Photograph: MCA

Figures of Speech, Abloh’s solo show at Chicago’s Museum of Contemporary Art in 2019. Photograph: MCA

The Illinois native is suitably open and expressive when he talks to me on a Zoom call from Chicago one winter morning. We fall straight into an animated conversation about his architectural background – he studied the subject at the Illinois Institute of Technology (IIT) in the early 2000s following a bachelor’s degree in engineering.

‘I’m an advocate for architecture school,’ he enthuses. ‘Some people would think it’s just about building buildings in the style of buildings, but the practice of architecture is a way of thinking.’ One, he says, that incorporates certain distinct elements – amassing extensive research (something he is famous for pursuing almost obsessively), defining a scope and ‘designing into a brief’ – which he applies to every project he works on.

As for making the slightly unorthodox leap from architecture to designing clothes, it was a stint dabbling in fashion design on the side while studying at IIT – creating T-shirts for a print shop in Chicago – which drew him into the orbit of, and ultimately a close friendship with, rapper Kanye West, with whom he famously embarked on an internship at Fendi in 2009.

Off-White pieces at the Figures of Speech show. Photograph: MCA

Off-White pieces at the Figures of Speech show. Photograph: MCA

Following this placement with the storied Italian fashion house – and numerous projects with West, including designing some of his album covers – it took just three short years for Abloh to strike out on his own, first with a brand producing modified deadstock Ralph Lauren clothing under the name Pyrex Vision, and then in 2013 with Off-White, the label that propelled him to stardom.

Abloh’s architectural training provided another boon for him in the chance to study the work of Rem Koolhaas and OMA – huge influences, he says, that revealed to him the possibility to ‘combine sociopolitical thinking with design’.

A keen sense of sociopolitical awareness certainly characterises the phenomenon that is Off-White. The brand is known – in addition to its liberal use of shapes and symbols redolent of signage one might commonly see on the street, including black and yellow hazard stripes – for its trademark of adorning anything from T-shirts to tulle dresses with words and phrases captured in speech marks.

These statements, at once decorative and provocative, are sometimes tongue-in-cheek (a wallet emblazoned with the words “For Money”) and sometimes not so (a T-shirt saying I Support Young Black Businesses featured in his autumn/winter 2020 collection), but make each piece a form of commentary on capitalist society in its own right.

Off-White’s own brand of sociopolitical thinking – its bold, often playful voice set among the po-faced seriousness of much of the luxury fashion world – might go some way to explaining its incredible popularity, particularly with millennials. The respected Lyst Index, a quarterly report that analyses the behaviour of millions of shoppers, has repeatedly ranked Off-White as the world’s hottest brand.

And Off-White’s star shows no sign of waning, not least because with its cult status has come the opportunity for countless collaborations, which Abloh moves through at an indefatigable pace. These come from all corners of the design world.

A recent collaboration with Mercedes-Benz saw Abloh redesign the iconic G-Class vehicle, adding, among other typically Off-White details, bold yellow text to its newly enlarged tyres, and eye-catching red safety belts. A 2019 range of Off-White furniture for IKEA – that Abloh once described as an exercise in ‘democratic design’ – featured items including a thick-pile green rug emblazoned with the words “Wet Grass”, and a minimalistic white clock with “Temporary” written on its surface.

Abloh has even had the opportunity to collaborate with AMO, research arm of his (now friend) Koolhaas’s OMA, on both the design of his Chicago retrospective Figures of Speech (2019) as well as that of Off-White’s Miami flagship store – an uncluttered concrete space intended to encourage people to gather for events. ‘I consider myself a creative,’ he tells me, when I ask if he always planned to move beyond fashion. ‘That means I have an idea for everything.’

Abloh’s prolific work with and through Off-White often toys with questions on the nature of creativity itself. In a 2017 lecture to students at Harvard’s Graduate School of Design, Abloh revealed that he espoused what he calls the ‘3% approach’ – that of ‘editing something 3% from its original form’ to produce something novel. A wildly successful collaboration with Nike released that same year, for instance, saw 10 iconic sneaker silhouettes given just minimal tweaks – a slogan here, some chunkier stitching there.

This approach is something that, over the years, has drawn its fair share of criticism from the press and fashion watchdogs alike – accusations of, at best, a lack of originality, at worst, plagiarism. But Abloh says we only need to look to the readymades of Marcel Duchamp, a hero of his, for a precedent of this kind of approach – of working with extant objects to create something new and radical. ‘I never once tried to claim to be an inventor or superior,’ he tells me. ‘I’m simply telling stories, drawing adjacencies, highlighting things as a part of a creative practice.’

In Project Geländewagen (2020), Abloh collaboratively reimagined the Mercedes-Benz G-Class. Photograph: Bafic

In Project Geländewagen (2020), Abloh collaboratively reimagined the Mercedes-Benz G-Class. Photograph: Bafic

In fact, to claim any work as purely original in this day and age borders on hubristic, he suggests: ‘Ultimately, it’s just like saying, “Hey, I am next to divine, I created something; if I wasn’t on earth this wouldn’t have existed.” You know, that taps more into humanity’s desire to, in a way, seem superior to the system as a whole.’

Abloh has been artistic director of menswear at Louis Vuitton since 2018, and his appointment there was a significant one. As the child of Ghanaian immigrant parents, he became the first person of African descent to hold the position at the historic French fashion house. His Louis Vuitton collections hew closely to the brand’s signatures – including its classical tailoring – while also bringing a modern flair, including streetwear-inspired silhouettes, plus timely nods to current social issues (his latest collection, made in what he described as a ‘year of reckoning’, featured an all-black team of collaborators and touched on themes of race and his own Ghanaian heritage).

Though largely well received, his work at Louis Vuitton, too, often faces intense scrutiny – natural, to some extent, given he has responsibility for such a pre-eminent luxury brand, but sometimes, it would seem, as a result of something uglier. But criticism, he says, is par for the course when you’re a black designer in a traditionally white world: ‘It comes with the territory, it’s kind of like paying tax.’

Abloh photographed by Bogdan Plakov

Abloh photographed by Bogdan Plakov

Abloh talks regularly about the barriers he had to overcome in order to break into the design world (sometimes literally, as he recalls being refused entry to fashion week shows with Kanye West). Even when Off-White started to gain serious traction, Abloh was faced with constant reminders that he didn’t fit in, not least being told on a regular basis that he didn’t ‘look like a designer’, something he says he’s been told ‘I can’t tell you how many times’.

Along with the bias – unconscious or otherwise – that Abloh faces from within the institution, it’s clear that being such an influential black public figure comes with another set of challenges. In summer 2020, he was criticised for expressing concern at the looting of Chicago shops by Black Lives Matter protesters and later revealing on Instagram that he had donated just $50 to a protesters’ bail fund (he countered the criticism by stating that he had in fact donated over $20,000 to related causes overall).

Does the pressure to represent weigh heavily on him, I ask? ‘It’s not even a weight on me, it’s a weight on all of us of black descent,’ he says. ‘Obviously I don’t think it’s unfair, you know – it’s warranted,’ he says of being taken to account over the donation, but, he adds, ‘we that are oppressed still have the weight of education, communication, and can equally be sort of brought down by things that are untrue, just sensationalism.’

A desire to present his own narrative without the distortion that can come hand in hand with media representation is also, it seems, part of the reason that Off-White is what it is. ‘The advocacy work that I do doesn’t get the same impression on the algorithm as a pair of sneakers,’ he explains. (Most recently, Abloh set up the “Post-Modern” Scholarship Fund to foster inclusion within fashion.) ‘So I’ve embedded my advocacy within the design, within the product.’

Despite the vulnerability to attack that comes from inhabiting his exposed position, Abloh shows no signs of slowing his activity. When we speak, his second homewares collection for Off-White has only recently hit the shelves (the brand’s debut “Home” range launched in summer 2019, while its first furniture collection was launched in 2016). Released in partnership with luxury retailer 1stDibs, it sees over 80 ‘familiar items’, as Abloh describes them, given an Off-White spin.

There’s a classic black comb updated with whimsical Swiss-cheese-like hole detailing (these so-called ‘meteor’ holes are an Off-White trademark, and found on other homeware items including a new stationery range). An Escher-esque design of overlapping graphic arrows (another motif that will be familiar to fans of the brand) appears on wallpaper and a cylindrical stool.

When we speak, Abloh’s immersed in preparation for Off-White’s next fashion collection, as well as that for Louis Vuitton (‘the biggest, most ambitious one to date – with each one I try to move the needle forward’). With so many balls in the air, I ask if it’d be fair to describe him as restless. ‘At certain points in my life, I’ve been like, I’m fucked up,’ he laughs. ‘But then I rationalise that when you say names like Karl Lagerfeld, when you say names like Steve Jobs [or] Michael Jordan, their practice is their life and their life is their practice.’

Adamant that his work is not driven by ego, Abloh says it’s a desire to encourage participation from a new generation of creatives of colour that pushes him forward. ‘I’m here to be an inspiration to kids that were like me, are like me, that didn’t believe that design was for them. That starts and ends my design mission.’

Despite his own successes, Abloh says that so much still needs to change in the design world: ‘This is generational work, nothing could have happened in my lifetime that is enough.’ But for now, all he can do is keep doing what he’s doing. ‘I’m a son of two African parents who came to America to give their children opportunity. I could easily be the kid in Accra, Ghana, with limited means, without the access,’ he says. ‘So the fact that I have it, the privilege that I have – every day I wake up and think, what can be done?’

This is an archival piece from Spring 2021