|

|

||

|

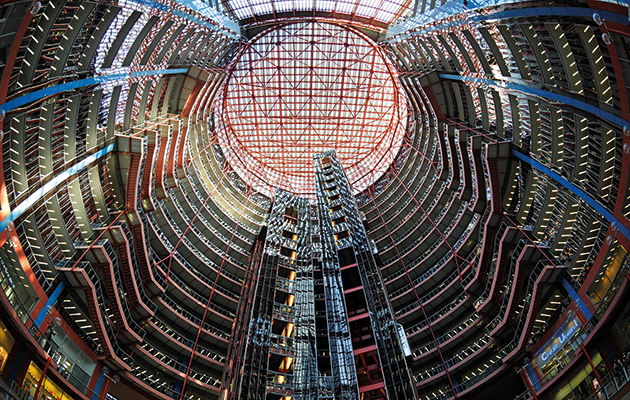

Helmut Jahn’s Chicago showstopper remains one of the most scintillating monuments to the 1980s’ deregulation of style, says Adam Nathaniel Furman The state of Illinois Center by Helmut Jahn, opened in 1985, sits in Chicago’s downtown like an all-singing, all-dancing, strobe-lit carnival float gate-crashing a funeral. It takes up an entire city bloc, is 17 floors high, is mirrored, scalloped, canted, coloured, decorated, striped and historicised. It’s about as subtle as an exploding meteorite. It revels in its shininess, and it flaunts its singularity. It is easy to forget just how exciting the opening-up of architecture was around this time. Like the markets, style was deregulated, decoupled from the stale dogmas of a ubiquitous and super-boring modernism. Philip Johnson stuck a gigantic Chippendale split pediment on top of a skyscraper; Michael Graves put colourful ribbons and cartoon colours on a government building in Portland; Stanley Tigerman built a house in the shape of a conjoined ejaculating penis and vagina. This was an era in which those architects who were willing to accept this brave new world of aesthetic liberty were free to design as they wished, to forge a ‘style’ of their own, and sometimes in the process become one of the new breed of world-famous, celebrity architects. And no one was better at it than Helmut Jahn. Philip Johnson made the cover of Time, but Jahn was on the cover of GQ. Graves built projects that looked like giant Lego sets, Johnson built towers that appealed to the polo-necked Hamptons set, but it was Jahn who forged a look that was to best represent the contradictions, paradoxes and obscene pleasures of the time. The dapper Bavarian, with his Versace suits and trademark hat, was referred to as ‘Flash Gordon’ and, living up to the moniker, he brazenly and often brilliantly smashed together high-tech, modernism, historically referential postmodernism, pop, googie and art deco, with a flair unmatched by any other architect. It was rare for all these to be present in one design, yet the epic scale and public nature of the Illinois Center was his chance to do just that, and he went all-out, producing one of the most spectacular and inscrutable buildings of the period. The full-height atrium is floored in stone paving reminiscent of Michelangelo’s Campidoglio; the atrium walls look as if the Centre Pompidou, replete with its high-tech paraphernalia and primary colours – has been turned inside out and crossed with Piranesi’s Carceri d’invenzione. This is a visually saturated, theatrical interior in the grandest manner, open to all: it is mad, futurist pomo, for the people. The Center’s external volume is treated as one huge sculpted shape, sliced at odd angles by the site’s edges, reflective and curved like a consumer electronics product blown up to impossible proportions, then clad in a decorative, stripey version of the curtain wall. This seductive alien object, known by locals as the Star Wars Building, sits on an abstracted classical colonnade of pink and grey granite that used to extend out around the plaza in front, decaying as it did so into a ready-made ruin, crumbling into the city as if the classical could not exist without the hyper-modern. With the wisdom of the crowd, Star Wars is an apt comparison: a mass-market media product in which the future became the same as the ancient past (a long time ago, in a galaxy far, far away). Jahn’s Illinois Center managed to rediscover the excitement of the future, something very much lost in the march of sub-Miesian tombstones, while incorporating the romance of a glamorous American past, all orchestrated with a virtuosity and ease that made the building instantly consumable. The Center is now in danger of being sold by state governor Bruce Rauner. If this happens, it would, in all likelihood, be demolished. Much architecture of the period was obscure, glib or, as Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown proudly proclaimed, ugly and ordinary. Despite technical failings (the client cut costs and used single glazing, turning it into an oven for half the year), the Center is none of those things, and stands as a monument to the virtues of hyperactive expression, wilfulness, joy and virtuosity over the usual cerebral restraint and hermetic smoothness of high architecture. Flash Gordon’s Star Wars Building still sparkles and scintillates, and should continue to do so long into the strange and exciting futures that its bizarre design has always hinted at. |

Words Adam Nathaniel Furman |

|

|

||