|

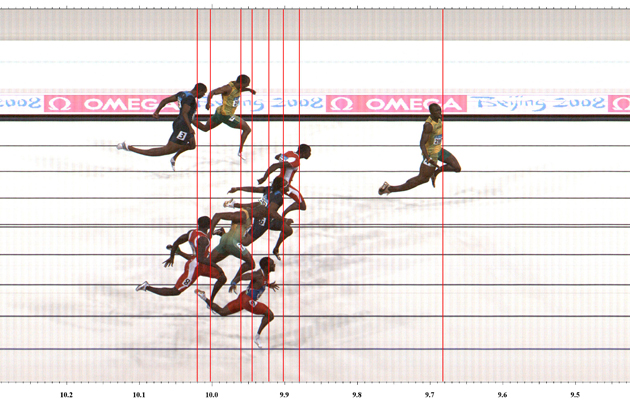

Usain Bolt breaks the world record in the Beijing 2008 Olympic men’s 100m final |

||

|

First used to expose corruption in horse racing, the eerie photographs taken by finish-line cameras have become the defining images of the world’s most dramatic races Usain Bolt left his competitors trailing at the 100m sprint final of the 2008 Olympic Games, setting a new world record of 9.69 seconds. Watching as his foot crossed the line was the camera responsible for providing the photo finish image – indisputable proof of the winner (not that it was needed in Bolt’s case), and of all the competitors’ official finishing times. A photo finish camera works using strip photography – a sensor is fixed on the finish line from a high angle, taking a rapid succession of images through a narrow slit as athletes cross the line. The images are then arranged horizontally: the white background is the finish line’s multiple reproductions. The eerie quality of the image, especially where body parts are shown warped or elongated, is a result of the method. Limbs look longer if they are stationary and appear cut off if they move faster than the film is moving. The objectivity of the method comes down to a mind-bending switch of space and time: where a regular photo shows various location points at one instant, a photo finish shows the same location at various times. The switch means there can be no ambiguity about the position of the racers due to oblique viewing or the error of the naked eye. Despite the high stakes – in cycling, rowing and speed skating too – the photo finish took a while to gain the trust of the sporting world. Eadweard Muybridge, pioneer of motion photography, saw the potential for a camera to determine a race’s winner as early as 1882 in a letter to the journal, Nature. In the 1940s, corruption in horse races motivated development of the first working models, which would have cost a racetrack £2.5m in today’s money. The first Olympic use of the photo finish camera was in London, 1948. Known as the “Magic Eye”, it was the joint effort of Swiss timers Omega and the British Race Finish Recording Company. But the technology failed to catch on, and it took another 20 years for its use to be legitimised. One of the method’s great campaigners was Omega engineer Jean-Pierre Bovay, who was moved to act after the 1960 Rome Olympics, where he observed three different times being manually recorded for the same swimmer. It took until Mexico 1968 for the finish to realise its potential, when the Games switched to being exclusively timed by electronics. Even then, the move was tentative; 45 manual timekeepers were sent to Mexico as back-up. At those Games, photo finish cameras filmed ten new world records and proved popular for being fast as well as accurate, able to develop an image 30 seconds after the result. As athletes get faster and records break, it is hard to imagine relying on human effort to keep up. The accuracy of the photo finish is a continuous work in progress, improving resolution, speed and sensitivity to light. At the 2008 Games, Bolt’s finish was recorded by a camera capable of recording 3,000 images per second compared to the previous 1,000. Bovay, in a short film on show at the Olympic Museum’s Chasing Time exhibition, describes the photo finish as a watershed in sports timing: the only true way to determine a winner that is ethical, objective and free from manipulation. Chasing Time at the Olympic Museum in Lausanne runs until until 18 January 2015 |

Words Riya Patel

Words: Swisstiming; IOC, John Huet |

|

|

||

|

|

||