|

|

||

|

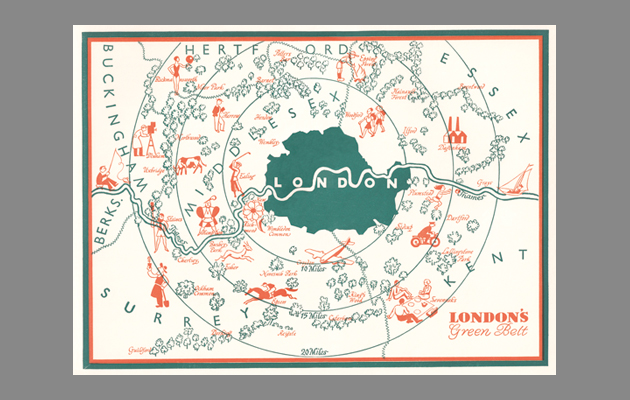

It may not all be publicly accessible, it may not even all be green, but the patchwork of protected land around London is a triumph of the social democratic spirit – the planning equivalent of the NHS In the politically charged debate about development in the UK, the Metropolitan Green Belt (MGB) plays a central role, appearing as either hero or villain depending on where you stand. For many, including the Campaign for the Protection of Rural England and the National Trust, it forms a last bulwark against the destruction of the countryside. For developers and neoliberals it represents an unjustifiable form of market regulation, pushing up land prices and interfering in the immutable laws of supply and demand. What these groups share is an understanding that the MGB represents an extraordinarily powerful piece of legislation that has shaped London and perceptions of the UK since it came into effect 75 years ago. Despite this recognition of its importance, and its iconic role in contemporary British politics, it is easy to miss the fact that the MGB Mapping the MGB – finding out what it actually consists of – is a fascinating process in itself. For a start, it contains a lot that isn’t green. A map of the territory is pockmarked by development, by towns and villages that, although found within its limits, are not actually green belt themselves. Outside these black spots, much of the MGB consists of land that exists somewhere between open countryside and development – in-between places with ambiguous qualities. Ex-industrial sites, airfields, landfill, reservoirs and intensive agriculture further erode the “green-ness” of the green belt. There are also an awful lot of golf courses and other essentially private spaces that fall short of the popular idea of publicly accessible open land. In short, the character of much of the MGB is far from the picture of unspoilt rural bliss that it has become in the pages of the national press. All this is not to say that it doesn’t serve a profound purpose. It has undoubtedly acted as an effective constraint on London’s development and remains a public commitment to preserving land for the common good. Its origins lie in reactions to the new suburban development of the inter-war years. During that period, writers including EM Forster and planners such as Sir Patrick Abercrombie campaigned against what they saw as the oncoming tide of unconstrained sprawl. The resulting legislation allowed councils for the first time to protect land from development by designating it as green belt. In many ways, this legislation was the planning equivalent of the NHS, a critical component of the social democratic project that defined the post-war political consensus. No wonder then that it has become a political flash point, although given the internal contradictions of British politics, the sides are by no means self-evident. Nimbys come in all political colours and both of the main political parties are riven with differences over the issue. The MGB stands as a testament to a state-controlled vision of planning and of how development should occur. It grew out of a belief in the democratic accountability of planning to act on behalf of us all. More than that, it was a bold attempt to map out a future, to say: this is how the world should be. Much more than a restriction, or simply a void where buildings don’t go, the MGB is a heroic piece of design in its own right. |

Words Charles Holland, David Knight and Finn Williams

Image: Kupfer-Sachs, from Fifty Years of L.C.C by SPB Mais (1939), courtesy of John Rogers, www.thelostbyway.com |

|

|

||