Cosmos, Cornell University, Ithaca (2012) – a homage to the astronomer Carl Sagan

Cosmos, Cornell University, Ithaca (2012) – a homage to the astronomer Carl Sagan

London’s bridges set to light up as art project Illuminated River takes place across the capital

This week, the Illuminated River Foundation will launch the creative lighting of 15 bridges across the Thames in London – the biggest single civic illumination project ever undertaken in the capital. The architect Lifschutz Davidson Sandilands (LDS) is collaborating with the celebrated Mexican-American light artist Leo Villareal to create the designs used connected LEDs from Dutch firm Signify, a process described as ‘painting with light’ and which required the biggest single planning application ever made without an act of parliament.

Here, read our profile of Leo Villareal from ICON 185, the November 2018 edition by Jay Merrick:

In November, the Illuminated River Foundation released the detailed designs for the creative lighting of 15 bridges across the Thames in London. The architect Lifschutz Davidson Sandilands (LDS) collaborated with the celebrated Mexican-American light artist Leo Villareal, and the designs were finalised via more than 30 individual planning applications across seven London boroughs.

LDS’s selection of the 51-year-old designer for the commission was as shrewd as the low-key visualisations they presented during the international Illuminated River design competition, whose shortlist included David Adjaye, Sam Jacob, Diller Scofidio + Renfro, Les Éclairagistes Associés, and AL_A. LDS knew that Villareal would not splash the structures with the lighting equivalent of bling. This was clear from his biggest and most important project to date, Bay Lights (2013) in San Francisco, which is claimed to have boosted the Bay area’s economy by $100 million.

Infinite Blooming, a site-specific installation at the Amorepacific Museum of Art, Seoul (2017). Photo by Inki Kang

Infinite Blooming, a site-specific installation at the Amorepacific Museum of Art, Seoul (2017). Photo by Inki Kang

Villareal spangled the superstructure of the western section of the 7.1km Bay Bridge linking San Francisco to Oakland with 25,000 LEDs fixed at 12in intervals, using 60,000 zip-ties. The LEDs, programmed by Villareal’s own software, can radiate 255 different lux levels to create a series of infinitely evolving light patterns.

The Thames bridges are minuscule compared to the Bay Bridge, with its 526ft high towers that carry the traffic decks 220ft above the sea. But the London bridges pose a vastly more complicated series of challenges because of the considerable differences in their architecture and individual histories.

The design process has been an integration of two approaches, according to Alex Lifschutz, co-founder of LDS. ‘Leo thinks from the general to the particular, and we think from the particular to the general. We’ve collaborated with artists before, but not on this epic scale. And he understands a great deal about architecture.’

Villareal’s contribution to the project will be more than artistic. He and his wife, Yvonne Force Villareal, are an established art-world power couple with celebrity status – and occasional fashion spreads – in beau monde publications such as Vogue and Avenue (‘Leo wears a Donners Cashmere Turtleneck Sweater by Theory. Velvet Blazer by Dolce & Gabbana. Faded Five-Pocket Jeans by Ralph Lauren Blue Label’). Which means that Villareal will generate substantial coverage in this particular media stratum when the Illuminated River lighting designs are revealed.

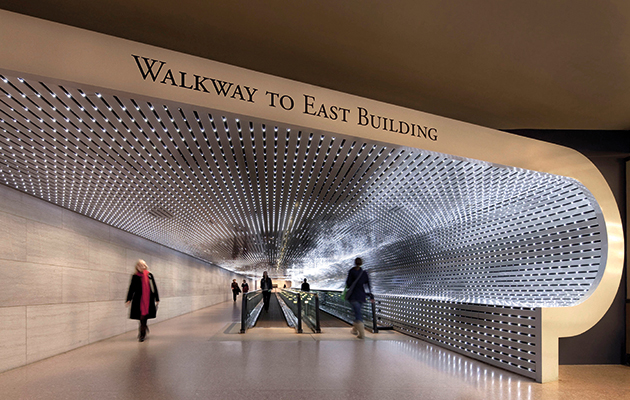

Multiverse, National Gallery of Art, Washington DC (2008): ‘Scintillating and almost trippy’. Photo by James Ewing

Multiverse, National Gallery of Art, Washington DC (2008): ‘Scintillating and almost trippy’. Photo by James Ewing

His installations are, however, implicitly critical of social or cultural elitism. In essence, the pieces express ephemerality, and usually in an environmentally linked way. Villareal is engrossed by concepts of artificial life and emergent behaviour, and sees his installations as living art generated by the digital alchemy of zeros and ones.

In the case of the Bay Bridge, the LED arrays are programmed to react to changes in the tides, weather and traffic flows. In New Zealand, Light Matrix (2016), the illuminated three-storey facade of the Auckland Theatre Company, is programmed to produce what Villareal describes as ‘playful’ effects.

His Volume (2015) and Light Matrix (2016) installations at the Smithsonian Institution and MIT take the form of big hanging sculptures composed of stainless steel rods embedded with LEDs that are programmed to create a cloud of shimmering patterns of light. At the Tampa Museum of Art, Florida, Villareal’s Sky (2010) draped a facade with a 45ft x 300ft aluminium skin covered with LEDs. And the 41,000 LEDs in his Multiverse (2008) installation in the tunnel-like concourse linking the east and west wings of Washington DC’s National Gallery of Art create scintillating, almost trippy effects.

Villareal’s route to art and architectural installations began at Yale College in 1990, where he gained a degree in sculpture and set design, and hung out with artists such as Matthew Barney. He then took a postgraduate degree in interactive telecommunications at New York University, and was an intern at the think tank set up by Microsoft co-founder Paul Allen. The road to Villareal’s LED-lit Damascus also passed through fascinations with the cellular automata systems created by the mathematician John Conway, the raw visual effects in paintings by 19th-century artists including Turner and Whistler, and the late-20th century artworks of Dan Flavin and Mark Rothko, among others.

The decisive moment came in Nevada’s Black Rock desert, during the 1997 Burning Man festival. Villareal rigged up a strobe-light array above his tent so that he could find it more easily in the hippy redux hurly-burly. Four years later, he was exhibiting artworks in Mexico City and Brooklyn. By 2010 his work was being toured in Survey, a substantial travelling exhibition.

Villareal’s installations are driven by sophisticated programming algorithms, ‘physics engines’ that create light patterns which constantly form and re-form in unpredictable ways. There’s a particularly clear insight into his ideas and methods in the way he explains his Auckland installation. ‘My work is really sequencing,’ he says. ‘The Light Matrix was created site-specifically and I sat here night after night programming it and tuning it and adjusting it. I use a lot of physics, and a lot of particle systems, things that you would find in nature, to drive the sequences. They’re all abstract. There are no images and no text. There’s a highly subjective aspect to it. And there’s no beginning, middle and end. It’s all randomised – so, in a way, it lets the viewer off the hook. They haven’t missed anything. There’s nothing to get. But that’s somehow very powerful.’

He sets up certain start-conditions for light patterns, without knowing how they will evolve. ‘And I wait for that one per cent of time when something [visually] compelling occurs, and I capture those moments. It’s really very compositional.’

Sky, an LED-studded aluminium veil for the Tampa Museum of Art, Florida (2010). Photo by James Ewing

Sky, an LED-studded aluminium veil for the Tampa Museum of Art, Florida (2010). Photo by James Ewing

He regards light as physically and psychologically primal: ‘It’s almost like staring into a fire – but it really connects people.’ In the case of the Auckland installation, ‘The next thing you know, people are talking to one another, and you’re connecting people and binding people and creating community. To see that happen is pretty powerful. It’s really exciting to make something which is deeply integrated into the city.’

And he adds: ‘We’re dealing with a lot of information all the time and there’s a real media agenda – you know, messaging and texting all the time. These installations offer a kind of break from that because you get to engage with that same seductive technology – but there’s no message. You can come up with your own track through it.’ Or, in the case of Illuminated River, bridge through it.

This article originally appeared in ICON 185. Subscribe here and never miss an issue