|

|

||

|

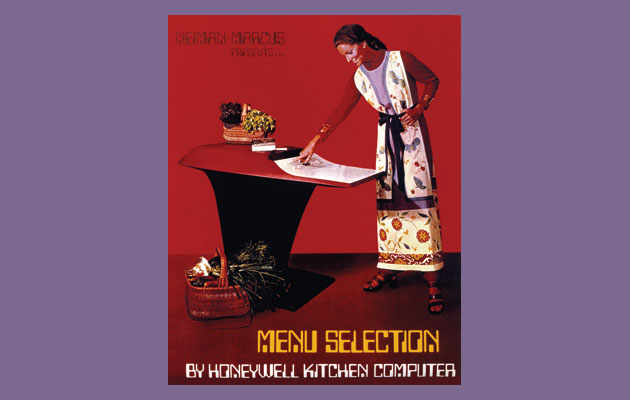

Is it worth sacrificing control of our lives just so the fridge can order in some more preserved lemons when we run out, asks Edwin Heathcote? There are some things that always seem to be about a decade away. Virtual reality, commercial space travel, artificial intelligence and so on. And then there are some things that seem like they ought to be closer. But somehow aren’t. Such as the Internet of Things. Anyone who has ever been unable to get online, then encountered an instruction to go online to find the solution, might understand my profound misgivings about networked technologies as the future platform for everyday existence. Last week my laptop packed up. I was unable to do anything at all. On the other hand, my heating still worked. And so did my retro-looking – but actually just old – LED radio alarm clock. And the fridge. Admittedly the clock on the cooker has gone funny, flickering green indications of some tech/existential breakdown. But generally, it all works. But will it once the Internet of Things takes a hold of everything? Currently, I have light switches, most of them probably dating from the 1970s or 1980s. These are simple mechanical/electrical devices that I understand. If they stop working, I can fix them. If they become digital devices they are lost to me. This is, of course, exactly what the corporations want. It is not enough for them to know everything about your life (from acute sensors able to detect temperature variations indicative of intercourse occurring in a room, to insurance premiums rising as forbidden foodstuffs leave the fridge), the Internet of Things also represents an astonishing leap for planned obsolescence. Soon, each jump in technology will see us needing to replace everything, from the cooker and the car to the switches and the clock. The idea, of course, is that all your devices will be able to talk to each other. Your fridge will let you know that you’ve run out of preserved lemons and stick it on your internet shopping list. So that the previous jar that it took you three and a half years to finish will be replaced instantly. I’m happy doing my own shopping; I don’t want to entrust my diet to my fridge. We’re told that our heating will programme itself according to our rhythms. I’ve spent my adult life avoiding any kind of regular activity. I like the chaos. And I like setting my own temperature. It will be more efficient, more sustainable. Will it? Once everything is electronic and needs to be kept going all day? The sci-fi dystopia side of all this is the corporate surveillance. The Internet of Things is, of course, what corporate commercial culture wants more than anything. It will finally tie you into your internet provider, your supermarket, your choice of brand for appliances (as none of the brands will be able to actually communicate with each other – think of the useless old phone and laptop chargers you have in a drawer, each one just different enough to the next). Resilience is not based on everything being dependent on everything else – on one system, one programme or one corporation. Quite the opposite. Worse, the Internet of Things and its corporate overseers will be able to see which room you are using, what you are doing in it, how many showers you take, how long you take in the shower. They will be able to switch everything off if they don’t like what you’re doing. Or report it. Your house will spy on you, becoming not a refuge but a snitch. The Internet of Things is a system. I don’t want to live in a system, I want to live in a home. I can turn my heating up when it’s cold and I’ll realise that I’m running out of milk without my fridge telling me. I hope the Internet of Things will always be a decade away. |

Words Edwin Heathcote

Image: Volker Steger/Science Photo Library |

|

|

||