It was designed to withstand German torpedos and has stood up to pretty much everything that’s been thrown at it since, from hamburgers to cheap imitations. By Lia Forslund

Wilton C. Dinges, engineer and factory owner, arrived early, yet the room was already filled with generals and military officials. Dinges and the military buyers were meeting for the first time in a hotel in downtown Chicago. Introduced as the owner of the Electrical Machine and Equipment Company, or Emeco, a metal workshop from Pennsylvania, Dinges stood before these figures of federal power with only an aluminium chair in his hand.

The year was 1944, and the men remarked on the lightness of the chair. ‘It would be perfect for the new submarine we’ve just acquired, but will it last on a navy ship?’ Dinges guaranteed that it would be impossible to break the chair, adding that it would indeed be non-corrosive and torpedo-proof. The men laughed and looked at the lightweight chair before them. ‘Let me demonstrate,’ said Dignes, ‘I will throw this chair out of the window, only to return it to you in perfect condition.’ The men could not believe what they saw. The chair fell eight floors before hitting the concrete pavement. It was brought back without a scratch. The government contract for the 1006 Navy chairs was signed that same day, specified as being for a chair capable of withstanding fire, weather, war and sailors.

Making an aluminium chair is easy; the great challenge is making it last. In 1940s America, the public collected used aluminium for the metal factories on the East Coast to up-cycle into military equipment. The ethos applied was circular, taking something discarded and making it stronger. In recycled aluminium terms, that entailed anodising, bathing and baking the used metal using thermal treatment until it became three times stronger than steel. Real events bring out certain and sometimes pure interests. Dinges used an unprecedented amount of engineering and craftsmanship for a single chair, hand-making a design object in no fewer than 77 difficult steps. Nearly every treatment was a separate skill with rigorous complexity: cutting, forming, welding, grinding, heat-treating, finishing, baking and polishing. However, the belief in longevity was linked to American pride at the time, intensified by the war. Dinges’ masterpiece was ordered in the hundreds of thousands, shipped by a train that went straight into the factory, and distributed to every American institution, from police stations and prisons to bars, diners and hospitals.

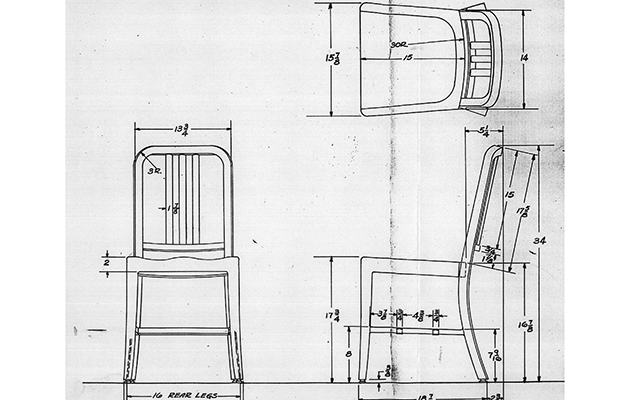

The Navy chair is not a record of functionality so much as a record of resilience. With a simple silhouette, tapered legs, three vertical bars in the backrest and an ergonomically moulded seat, the chair became a design icon—simultaneously invisible and present. Over time, it came to represent America as one of the most frequently used scenography props, featured in hundreds of films and television series. This is part of the journey of the Navy chair, which made it respected at home and abroad.

Every icon has its followers; sometimes this leads to third-party interpretations, sometimes to counterfeit appropriations. During the 2000s, the Navy chair became widely used in restaurants and bars, partly because of its guarantee of lasting 150 years in public use. The quality control of the chair was in fact so strict that it included a hamburger stress test, in which a warm burger was smudged on the seat to test resilience to acid. Inferior copies soon started to flood the market. In a fast-food restaurant at Las Vegas airport, a person was injured after a fake chair broke. To the customer, the chair looked authentic. These incidents became problematic, and prompted proactive counter-measures from Emeco.

In autumn 2012, the exploitation of the Navy chair silhouette reached a turning point. An American furniture company called Restoration Hardware was sued for what the judge ruled as ‘willful and flagrant infringement of Emeco’s trade dress’ when selling a near-identical ‘Naval Chair’. It was the first in a series of settlements, several with mass market brands including Ikea and Target.

For such infringement claims to be upheld in a US court, the plaintiff needs to prove their object’s inherently distinctive cultural meaning. The Emeco chair – featured in books and museum collections, well known around the world, stands for a belief in something that will last. A moment in history when a metal engineer rigorously composed a chair with military precision has become a symbol of mid-century American spirit. It also stands for a belief in circularity, encouraging people to perceive design in terms of recycling improvement. If only more chairs could take an eight-floor fall and last a lifetime.