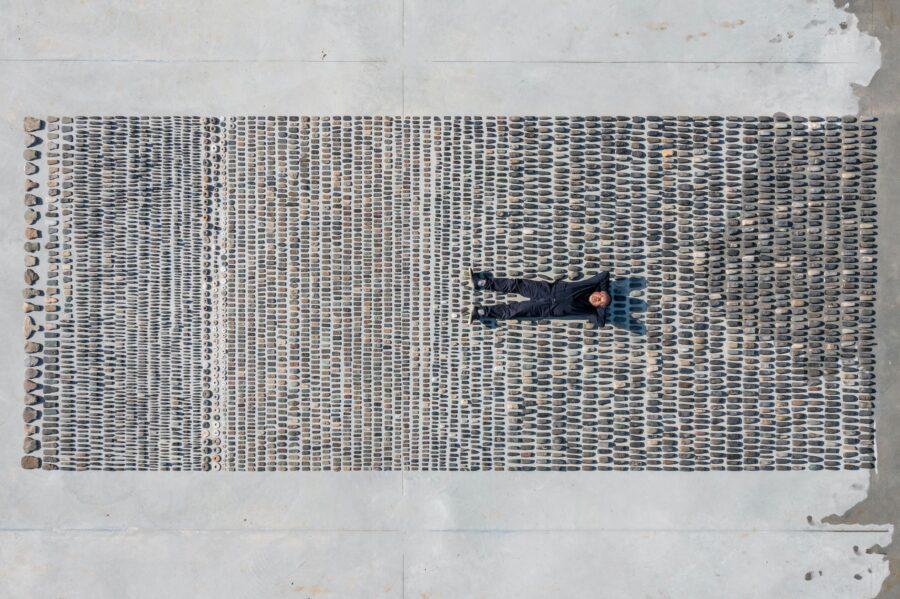

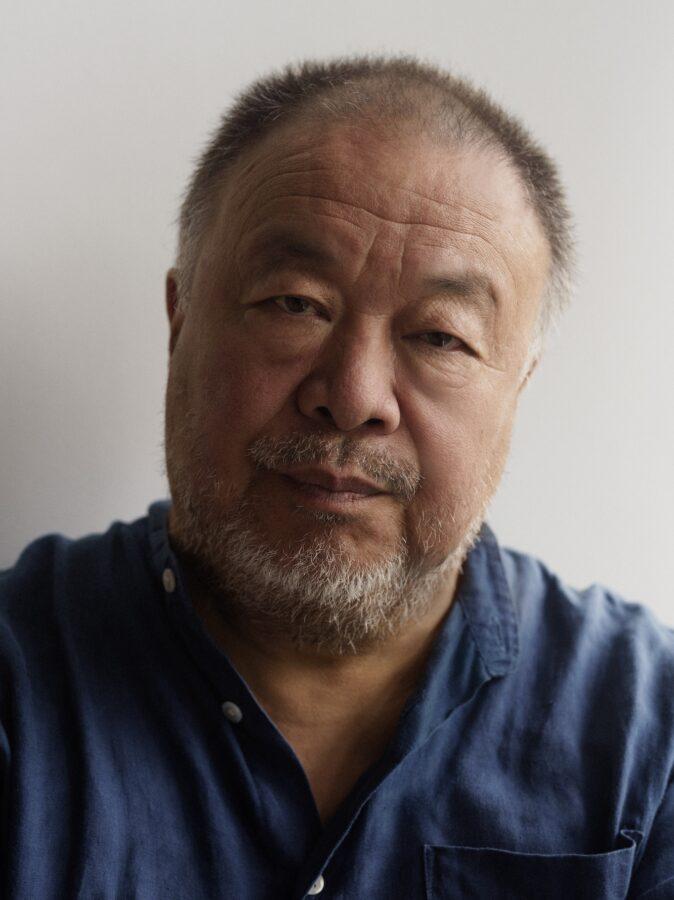

As an artist and activist Ai Weiwei has received global recognition. Now a new London exhibition is taking a closer look at his work through the lens of design

Photography by Ela Bialkowska, OKNO studio, courtesy of Ai Weiwei Studio, Water Lilies

Photography by Ela Bialkowska, OKNO studio, courtesy of Ai Weiwei Studio, Water Lilies

Words by Joe Lloyd

Ai Weiwei is a colossus bestriding world of art. Every year, a cache of museums across the planet exhibit his works old and new. He is a multimedia figure, whose works range from 10-hour films examining the Beijing cityscape to a cover of the surprise 2012 sensation Gangnam Style.

The dreadful injustices of his personal life – which have seen his studio destroyed, him beaten by police, placed under house arrest and later jail on false charges of tax evasion – have helped make him an emblematic figure of our time, and fuelled the idea that artmaking can serve as a form of resistance.

This spring will see the largest UK show of Ai’s work in over eight years. It will feature several of his most significant works, including site-specific ‘fields’ of Song Dynasty porcelain cannonballs, Lego bricks and his smashed-up ceramic sculptures. But instead of being hosted at the Tate Modern, the Hayward or Barbican Art Gallery, Ai’s big London return will take place at the Design Museum.

Photography courtesy of Ai Weiwei Studio

Photography courtesy of Ai Weiwei Studio

‘This major exhibition,’ says the museum, ‘will be the first to present his work as a commentary on design and what it reveals about our changing values.’

One might well wonder about this relationship. It has often been said that the boundaries between art, design and other disciplines are collapsing. Blue-chip artists like Jeff Koons work with fashion labels; design studios like FormaFantasma present exploratory exhibitions at art galleries; the Assemble architecture collective won the Turner Prize, and so on.

The border between art and design has never been that starkly drawn: the greatest sculptor of the Italian baroque, Gian Lorenzo Bernini, was also among its finest architects; Le Corbusier was a better-than-average Cubist painter.

Photography courtesy of Ai Weiwei Studio, Glass Helmet, 2022

Photography courtesy of Ai Weiwei Studio, Glass Helmet, 2022

‘Today,’ said Ai in a 2017 event at Columbia University, ‘I think architects and artists need to work across disciplines and in many different mediums. It’s not so linear anymore.’

A key difference now, however, is in terms of purpose. Artists historically created prestige works with aesthetic rather than functional value, while designers created those lower-status objects and things that were useful to society. But in recent decades, art has taken a social turn, with many practitioners devoting themselves to finding solutions to society’s problems, in a loose alignment with design thinking.

Ai has been at this from the beginning. In the early 2000s, he presented a series of film works investigating living conditions in Beijing. More recently, he has created a number of pieces, including a cinematic feature, that serve to raise awareness of the global refugee crisis.

Photography by Rick Pushinsky for the Design Museum

Photography by Rick Pushinsky for the Design Museum

Ai’s work also abounds with design objects, in particular ceramics. During the Cultural Revolution, antique Chinese objects and furniture were systematically destroyed, following Mao’s dictum that ‘without destruction there can be no construction’. Many of Ai’s early works sought to interrogate this description of traditional objects. Early in his career he acquired a pile of ceramic urns and painted them over with the Coca-Cola logo.

His notorious 1995 performance Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn saw him let an ancient ceramic jar fall and smash; he has since cut up a Ming dynasty table and reconstructed it. But he has also commissioned contemporary artisans to create new versions of traditional furnishings. For his Marble Chair (2008), a replica of his family’s old yokeback armchair was carved from a single block of marble.

The field of design where Ai has truly made his mark is architecture, however. In 1999, he built his own home and studio in Caochangdi, a now-demolished artists’ village in Beijing. Four years later he founded the studio FAKE Design, which gradually became responsible for around 70 projects.

Photography courtesy of Ai Weiwei Studio, Coloured House, 2015

Photography courtesy of Ai Weiwei Studio, Coloured House, 2015

His most prominent architectural achievement came in collaboration with Herzog & de Meuron, with whom he designed the Bird’s Nest Stadium that hosted the 2008 Beijing Olympics. He also worked with the Swiss firm on Ordos 100 – a shelved project that would see 100 young architects each design a villa for a new town in Inner Mongolia – and the 2012 Serpentine Pavilion.

Ai’s projects have slowed and scaled down since his departure from China in 2015, but he still continues to practise: in 2021 he collaborated with the studio Reddymade on a house extension in Salt Point, New York. Few figures today have rendered the borders between disciplines this fluid. Making Sense may mark a key moment in the ever-closer relationship between art and design.

Ai Weiwei: Making Sense runs from 7 April – 30 July 2023 at Design Museum, London

Get a curated collection of design and architecture news in your inbox by signing up to our ICON Weekly newsletter