|

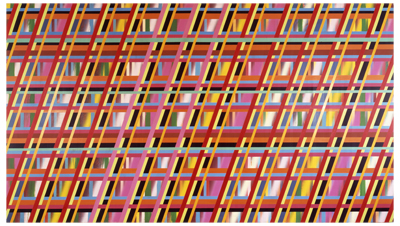

The artist talks about his forthcoming retrospective in China and how Fox News killed plans for his $1m sculpture for Kieran Timberlake’s new US embassy in London Irish-born artist Sean Scully is to have a retrospective at the Himalayas Museum in Shanghai from next month. “It’s gorgeous, a new kind of architecture, very theatrical,” Scully says of Arata Isozaki’s massive “archisculpture”, a neon-gridded box raised on a podium into which are carved a series of rusticated caves. His retrospective there, looking back over a 50-year career and including a new large-scale sculpture called China Piled Up, is being billed as “the first important exhibition in China of a major western abstract artist”. Scully’s work is fundamentally architectonic. Born in 1945, and twice nominated for the Turner prize (in 1989 and 1993), he shot to fame in the early 1970s with a series of hard-edged “Super-grids”, which he describes to me as “computer paintings before computers really existed”. These densely gridded works turn order into anarchy, with endless repetition of lines that culminate in visual overload, an effect intended to simulate the sensory effect of cities. Scully was inspired, he tells me, by Phil Spector’s idea of a Wall of Sound.

Blaze (1971), one of Scully’s “Super-grid” paintings After a visit to Mexico in the early 1980s, where he visited Mayan ruins, Scully’s work became increasingly infected with architecture. He began to challenge the orthodoxy of minimalism; his canvases became patchworks of different striped surfaces, with boxes, sometimes of different depths, that jigsaw together to create checkerboard works of earthy hues.

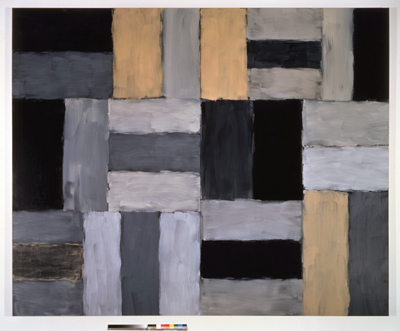

Wall of Light Desert Night, 1999 The late critic Arthur Danto wrote a 2007 essay on the “architectural principles” in Scully’s work, describing the stripes and slabs that interlock in his canvases as “walls of light”. Pursuing this motif, Scully published a series of black and white photographs of the ancient stone walls of Aran, and another on the similarly patchwork facades of the brightly coloured, weathered shanties with which he became fascinated in the Dominican Republic.

Shanty housing in Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic, 2000 His paintings are sometimes punctured, to create the effect of windows, and they explore rhythms of pattern and vibrating colour. “You can see one of my paintings from 200m and you can recognise it’s mine,” Scully says of his signature style. Recently, Scully has become increasingly interested in sculpture, some of which take an architecture scale. Wall of Light Cubed (2007), near the Marquis de Sade’s Chateau in Lacoste, resembles one of his paintings inflated to three dimensions: it’s 4m-high, 8m-wide and 20m-long. The rough-hewn, solid stack of stones from which it’s made are chalk-stripped, reminding me of the marks prisoners scratch on walls to count the days. Of course, de Sade wrote 120 Days of Sodom while imprisoned in his own Bastille.

Wall of Light Cubed, 2007 “When I was young, one of my first jobs was at Woolworths, bailing all the old cardboard boxes,” Scully says, telling me he’s just become conscious of this early influence. “When you look at my sculptures, which are essentially stuff piled up, and look at those packets that come off a bailing machine, there’s a beautiful relationship. A bailed block of cardboard boxes is a monumental sculpture – it’s already made.” Scully was due to create another huge granite block – “a beautiful tower” – for Kieran Timberlake’s new American embassy in London, a similarly Bastille-like building. “If you go around bombing people all over the world you have to build not embassies, but fortresses,” Scully remarks. The project was soon mired in controversy, with Fox News – “right-wing lying bigots, like the National Front”, in Scully’s description – objecting to the $1m commission and accusing the state department of corruption.

Proposal for the US embassy in London As it turns out, the sculpture was too heavy for the site (also the fate of a black stone piece Scully hoped to make for his Shanghai retrospective, to be called Heaven Cubed, because black is apparently the colour associated with the afterlife in China). “My sculptures weigh much more than buildings,” he explains, “because buildings have empty space in them.” Scully has decided to create a “gigantic ceramic painting” instead – a huge tiled mural featuring grids of his trademark stripes, which will no doubt cost less. Scully describes his blank-walled sculptures as “like buildings that have been filled in”. I ask him whether he’d ever like to create a piece of architecture proper. Scully talks with enthusiasm about his favourite living architect Tadao Ando, praising his Church of Light in Japan, with its negative cross on the altar wall, and his Modern Art Museum in Fort Worth, with its floating pavilions. “He was a professional boxer and I was a boxer too,” Scully says. And, of architecture, he adds, “you never know – maybe one day”. Follow the Heart: The Art of Sean Scully 1964-2014, opens at the Shanghai Himalayas Museum on 23 November 2014 to coincide with the Shanghai Biennale, and will travel to Beijing in February 2015 |

Words Christopher Turner |

|

|