|

|

||

|

The walnut-coloured launch bobs gently at the lake’s edge. The water is almost perfectly still and the morning clouds have lifted to reveal an encircling ring of mountains. It is an impossibly beautiful setting for an unlikely event. I am testing a speedboat or, at least, being taken out on one for something called a sea trial. We aren’t at sea and the boat has been out on this lake many times before; I am not going to argue with the terminology. The day before, my mode of transport had been a red bus trundling through the streets of east London. Tomorrow it will be again, but for today I can indulge any lingering fantasies I may entertain about being George Clooney and imagine a life spent escorting glamorous friends across the lakes of northern Italy. I slip off my shoes and step on to the launch. It would be nice to think that I did this with a certain élan, a casual sense of having done it countless times before. But no, I fluff it, taking a lunge at the boat and slightly losing my balance in the process. There is something about stepping on to a speedboat that makes you very self-conscious. It is one of those things that carries with it an almost unshakeable sense of privilege and luxury. The moment that comes so heavily overcoded with expectation that it has an air of unreality about it, as if it is not really happening. I don’t normally seek out “luxury” experiences. Glossy magazines featuring yachts and expensive watches are more likely to make me nauseous than envious. But it would be churlish not to be impressed by the sleekly beautiful object about to whisk me across the water’s surface. It is fast but in an unostentatious way, its twin V8 engines burbling away without ever being overly strained as we pick up speed away from the quay. The boat I am on is an Iseo, made by the famous Italian company Riva. It is named after the lake we are sailing on, which has been home to the Riva boatyard since 1842. Riva are renowned for their polished mahogany-hulled launches, sublimely crafted objects indelibly associated with Hollywood legends such as Brigitte Bardot and Anita Ekberg. The faces of these stars line the private museum of historic boats hidden away in a nondescript building at the back of Riva’s factory. In a single, windowless room, about 20 boats are arranged chronologically from the earliest, most basic launches through to the iconic boats of the 1960s and 70s with their Cadillac-like interiors and airliner-inspired fold-down drinks trays.

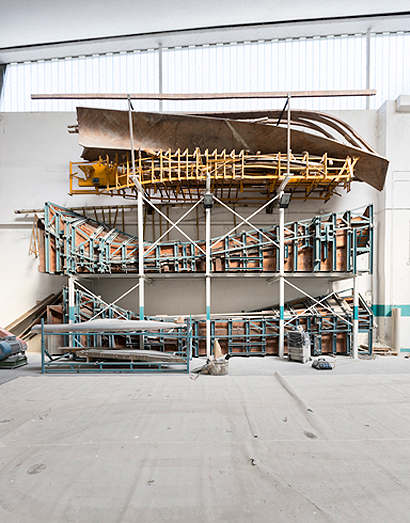

The Iseo is made not of mahogany but of fibreglass, as all Riva’s boats have been since the mid 1990s. It does have a mahogany panel at the front though to recreate the look of the famous prow as it dips up and down over the water. It was built across the road from the museum in the impeccably clean factory on the shores of the lake. At the front of the building, a boardroom cantilevers out over the lake like a Bond villain’s HQ. Inside it, pieces of boats are displayed like artworks, shell-like air intakes made of cast aluminium and shapely chrome holders for the famous Riva flag. The boats are assembled rather than constructed here now. Their fibreglass hulls and Yanmar engines are made elsewhere and put together by Riva along with the finishes, electronic circuitry and upholstery. As the boats move along the production line they acquire more and more protective layers of cardboard and foam. Towards the end they take on a strange patchwork appearance – highly engineered machines that have been roughly covered in the cheapest of materials. Wandering around the factory I come across the disused jig once used for bending the original timber hulls. It is a remarkable piece of equipment in its own right, indicative of a different period in the company’s history. Pietro Riva started Riva in 1842 as a repair shop before he began to construct his own boats. In the pre-Second World War era, it grew rapidly on the back of success in powerboat racing and record breaking. Its most famous years though were the 1950s and 60s, when it was synonymous with Pietro’s grandson Carlo Riva and the legendary Aquarama. Even if you know nothing whatsoever about boats – and until this visit neither did I – you are probably familiar with the Aquarama. It is the quintessential Italian speedboat, a teardrop-shaped launch made from lacquered mahogany inlaid with thin strips of blond maple wood. Its wraparound windscreen, edged in glossy white plastic, and aquamarine interior somehow manage to combine 60s grooviness with a restrained, classical elegance.

Carlo Riva sold the company in 1969, initially to US fibreglass company Whittaker. It is now owned by the Ferretti Group, although the Riva family still maintains the maintenance business located next door. Ferretti has picked up the pace of development again and launched a number of new boats as well as instigating collaborations with brands such as Gucci. The current range of boats spans from the relatively piddling 27ft-long Iseo to the monstrous 115ft Athena. The largest boat made at the Lake Iseo yard though is the 52ft Rivale. Riva’s ocean-going yachts are made at the company’s sister factory in La Spezia on the Tyrrhenian coast, where they are built to order and launched straight into the sea. There are plans for an even larger boat, a 122ft metal-hulled affair, that reflects the ever-increasing appetites of the super-rich. Unfortunately, I didn’t get to go on any of Riva’s larger boats. I would have liked to because, apart from this being pretty much my only chance, it would have been intriguing to experience a form of design intended for so few people. The cost and exclusivity of the current generation of super-yachts is both compelling and shocking, something that you want to experience simply because it might tell you something profound, if unsettling, about the modern world. The notion of luxury embodied by a brand such as Riva is worth unpicking. The current crop of boats is designed by Officina Italiana Design, but in recent years it has also worked with other celebrity designers. In 2010, Australian Marc Newson produced a variation of Riva’s Aquariva, available as a limited edition of just 22 and marketed exclusively through the Gagosian gallery. Newson’s design was in many ways a more accurate and stylish interpretation of the classic Aquarama than Riva’s own, but the way in which it was marketed as a piece of art is another thing altogether. The elision of high culture with luxury occurs in a mutually reinforcing atmosphere. Ultra-expensive brands like to align themselves with fine art to suggest that their appreciation is about something more than money. Simply being expensive is not enough. It is important that the owners of such things are admired for exercising their taste and sophistication as much as their financial muscle. Hence the constant use of words like discernment and connoisseur in the marketing of luxury goods. At the same time, artists and designers seem to go a little weak at the knees when catapulted into the world of the super-rich.

Brands such as Riva exist in a kind of eco-system of their own. They are a form of currency acceptable only in certain, exclusive places and this includes Art Basel at Miami Beach where Newson’s Aquariva was launched. Newson may have positioned his boat as a limited edition artwork but he did at least design one. The same can’t be said of the German artist Christian Jankowski, who merely displayed an Aquariva alongside a scale model of a mega-yacht made by CRN, another Italian boat builder, at the 2011 Frieze Art Fair. Jankowski offered visitors to Frieze the chance to buy the boats either at their normal list price or as pieces of art – titled The Finest Art on Water – at greatly inflated prices. The suggestion that even a hyper-luxury object such as the Aquariva can be made more valuable simply through the application of an artist’s signature was clearly intended as a satirical comment on the venality of the art market. But Jankowski’s somewhat shopworn point relies on there being some kind of friction or clash between the worlds of luxury goods and high culture. In fact, as the presence of all those super-yachts moored at the Venice Art Biennale testifies, the two worlds are already closely joined. Jankowski seems merely a complicit part of this process, at best a court jester aware of the absurdities. The concept of the Duchampian ready-made has surely passed the point of no return here; a self-regarding wink to cover up the most shameless of ideas. Bearing this mind, Norman Foster’s recent design for a limited edition super-yacht for the company YachtPlus doesn’t seem that different to Jankowski’s conceptual joke. Foster no doubt took the actual task of boat-designing reasonably seriously but, once again, the point is the bestowing of a signature high-cultural brand on to an already ultra-expensive product.

The appeal of this world for artists and designers is not particularly hard to fathom. Suggesting that Foster has somehow lost sight of his true path in designing a luxury yacht reminds me of the old joke about footballer George Best. Coming across the former maestro lounging on a hotel bed surrounded by glamorous supermodels and oodles of cash, the earnest sports reporter asks: “Where did it all go wrong George?” Leafing through the publicity material from my trip I am struck by the following question: why is the sight of a speedboat gliding over the water considered so luxurious? What exactly is the quotient of glamour in this overly familiar image? It seems on the face of it a slightly redundant question. Undoubtedly, it has something to do with the lack of utility involved. It’s not that speedboats aren’t functional exactly, more that the particular function they perform is unnecessary. A trip on a speedboat fulfils nothing other than itself. It’s not a journey that ever needs to take place. The point of the small speed launch is of course to go ashore from your much bigger yacht anchored off the coast. In that sense it is simply a way to move from one luxury scenario to another in the most glamorous way possible. It moves the very rich from one bubble of wealth to another. It is therefore perhaps the essence of surplus value and the ultimate commodity fetish object. Its desirability is in inverse proportion to its usefulness. Skipping over the water’s surface, I feel both exhilarated and heavily weighed down by expectation. It is a heady experience but in a funny sort of way it isn’t mine. I am there and at the same time I’m not, lost in a welter of heavily scripted images. At the end of it, the thin, weightless bubble of luxury bursts. The boat comes to rest and after a short while leaves nothing in its wake.

|

Image Gianluca Giannone

Words Charles Holland |

|

|

||