|

“We are not virgins. We really need to become naive again,” says Ronan Bouroullec. He and his brother, Erwan, have been working together for ten years. This is not a fact they are celebrating. “Maybe after ten years we are a bit lost now,” he confesses, and the more he talks, the clearer it becomes that the brothers are getting restless. They want to exercise new muscles – before the atrophy sets in. None of this is obvious from the outside. What we see is the most talented furniture designers of their generation, doted on by a design world that hangs on each new product with the brothers’ imprimatur. We see a pair of latterday Eameses, tuning their work to the shifting ground of the 21st-century flexiscape – an ambiguous world of room dividers, live-work fuzziness and walls of seaweed. We see an output that is rural yet urbane, arthouse yet occasionally mass market, full of charm yet serious. It takes two to pull off such contradictions. Are they bored of the medium scale, and, if so, will they move down to product design or up to architecture, or somewhere else altogether? A few minutes’ walk from Oscar Niemeyer’s Communist Party Headquarters, in a courtyard in the Belleville district of Paris that serves as Chinatown, is the Bouroullecs’ studio. It’s bright and calm, and has a productive air. The walls are pinned with semi-abstract drawings in coloured felt-tip pen and the worktables are piled with books. One pile is just architecture, topped with a monograph of Australian Glenn Murcutt – not an obvious point of reference but, it turns out, Ronan’s favourite architect. The first question an interviewer wants to ask a pair of brothers is how they work together. In Objectified, Gary Hustwit’s recent documentary feature about design, they describe themselves as a fox (Ronan) and a hedgehog (Erwan), using the philosopher Isaiah Berlin’s categorisation of intellectuals. The description promised an interesting insight into their work. According to Berlin, foxes (Mozart, Shakespeare, Picasso) know many things, but hedgehogs (Dostoevsky, Proust, Giacometti) know one big thing. “Ah, we didn’t know that,” says Erwan. It was a throwaway remark from “Mr Fehlbaum”, head of Vitra and their patron-in-chief, and it simply stuck. “Maybe we are a bit different in terms of psychological approach,” says Ronan, stepping in to describe how Erwan fights with Vitra’s technical director of 40 years. “In general I would arrive after the fight …” – to play good cop, he implies – “but sometimes he’s the bad cop, sometimes I am.” And what are these dustups about? All eyes shift to Erwan. “You need to be sure the work goes in the right direction and not get lost,” replies Erwan. “You need a certain approach which is more linked to pleasure, to desire, that makes you drive the project to something that is a little bit higher. We need to feed it with a lot of desire for the ‘other one’.”

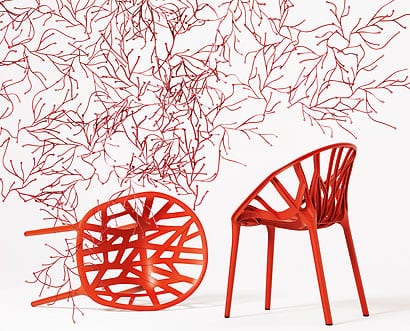

Vegetal Chair for Vitra, 2009, and some Algues screen segments, also for Vitra, 2004 (image: Paul Tahon/R&E Bouroullec) Ronan, 38, is sprightly and sketches the same chair over and over when he’s not talking. Erwan, who is five years younger, is otherworldly and will twirl his beard or bend a paperclip out of shape as he talks. Neither brother likes to be interrupted by the other but often one will pick up seamlessly where the other left off. What is it that makes the Bouroullecs interesting? Why, when Erwan refers to a “higher” furniture, does that sound like a compelling aspiration and not pretentious guff? When the brothers started out they were promising designers in a late-Nineties aesthetic of retro-futurism cornered by the likes of Marc Newson and Michael Young – think of the Cloud shelving for Cappellini or their first major success, the Joyn office system for Vitra. Since then they have become much more distinctive. Their work is instantly recognisable yet unpredictable. Inevitably, this comes from their approach: they are willing to push an idea to its seemingly impractical or absurd conclusion. Take Algue, a screen system made of dozens (or hundreds) of plastic coral-like branches that clip together to create a wall of seaweed. It’s more decorative installation than barrier. Who on earth is going to bother dividing their space up that way, you might think. Yet Vitra has sold more than 3 million of them. A connective network of dendritic veins, it is the screen analogy of the internet age as much as Prouvé’s chairs were analogues for the early years of flight. If there is an overriding theme to the Bouroullecs’ work, it is freedom – our freedom, to use their products the way we want to. The Joyn furniture system was aimed at the hot-desking, flexitime generation. The whole point was its adaptability. Since then their modular screen and furniture systems have articulated a culture of temporary solutions for nomadic lives. “The idea of flexibility is certainly, for me, one of the only big differences with the history of the last 100 years,” says Ronan. “The fact that you and me will have about ten different flats in only a few years … Adaptability is maybe the most important thing for the evolution of furniture.” To that end, the brothers go to great lengths to avoid their furniture being prescriptive. Erwan talks about trying to remove any signs “that could give the user the impression that you will not behave properly with the furniture”. This room to manoeuvre is central to their idea of comfort. It is why, for instance, the uniformity of the seats on the Paris Metro goes against everything they believe in (“so many different bodies, so many different ways of behaving”). One of their quirks is that they always insist on making chairs with arms – arms, specifically, that curl out of the backrest. “It just means that you can move inside the chair,” says Erwan, and as he does so he squirms slightly in his Vegetal chair, levering himself into a more comfortable position.

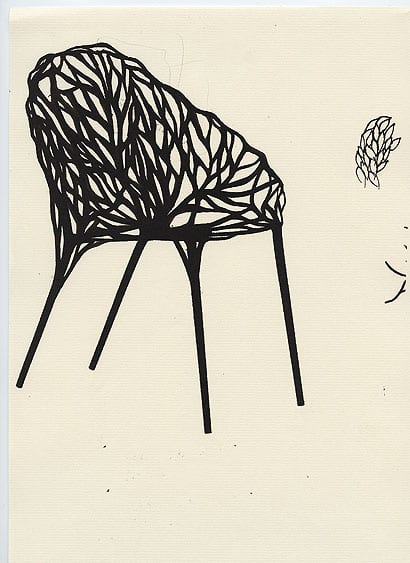

Vegetal chair for Vitra (working drawings), 2009 (image: Paul Tahon/R&E Bouroullec) There is a price to pay for this kind of single-mindedness. “It’s a nightmare in terms of royalties,” says Ronan. Armchairs don’t sell well because they take up more space and don’t fit neatly under tables. But commercialism will not dent the brothers’ definition of comfort. They are inflexible so that we can be flexible. And their manufacturers let them have their way. “For me,” says Erwan, “and this is what masters like the Eameses learned us, it’s really important that the furniture supports a certain need for freedom that people have. If you’re in the wrong position then of course your brain doesn’t feel free at all.” Erwan likes to describe their work as furniture “haute couture” – in other words privileged enough to exist as research or cultural statement as much as commercial product. He describes the screens as “hyper-positions: in a way a bit too extreme to become something totally real”. This is testament to the high esteem in which their manufacturers hold them. Most of their work has been for Vitra, which hardly ever gives them a brief or a deadline. Instead, ideas emerge through daily dialogue – more like a think tank than a design practice – and can take years to realise. This is why the Bouroullecs have become assiduous documenters of every stage of their working process. The Vegetal chair, again for Vitra, took four years to produce and as well as a chair has resulted in a book of drawings and maquettes. “Most of our projects exist more in pictures than in reality,” says Ronan. Flicking through the pages, you can see why they would document the research for the Vegetal chair: their tantalising drawings suggest wonderful potential. The injection-moulded finished product is inevitably an anticlimax, rather more solid than their imaginations desired. But they don’t just document for posterity’s sake, but to explain their work. “I think it’s getting more and more important to explain to the customer where things come from,” says Erwan, just back from a trip to the courtyard to smoke one of his Marlboro Golds. Computer-aided design, car design, everything is “becoming really unreal”, design as magic trick. Erwan would like to see design take a tip from organic food, with the provenance meticulously labelled. “The customer likes to know what he’s buying.” The organic – or, rather, nature – is another obvious presence in the Bouroullecs’ work. Room dividers that are algae, clouds or rocks, lamps with bell flower heads (the Blacklight for Galerie Kreo). There is a rural quality to all this – a naivety, almost, that sets them apart from the urbanity of many of their peers. The brothers grew up in the countryside, in Brittany, but they’re not sure how much weight to ascribe to that. “When you are French it’s a little bit difficult to explain,” says Erwan, “because the French design story has been revolving around art deco and decoration, and when you come after [Philippe] Starck, who has been using this old craft tradition, and when you are making just the opposite, everyone asks you ‘Is it because you were not born in Paris?'” He chuckles and gives it more thought. “It’s true that we have been exposed to the countryside, and I can imagine it has been imposing in the back of my mind a desire for this rough quality.”

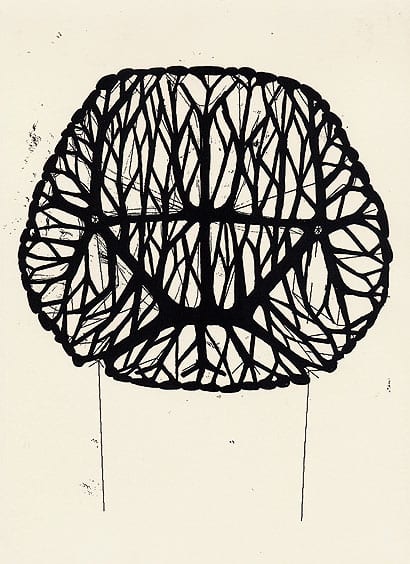

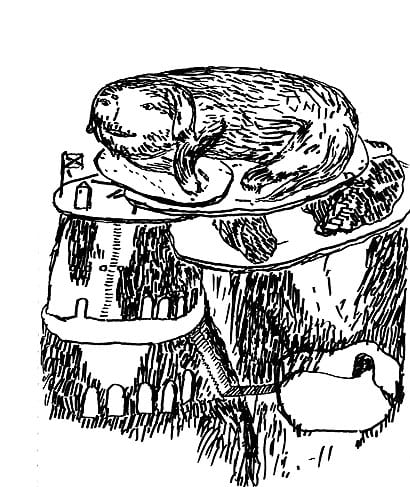

Vegetal chair for Vitra (working drawings), 2009 (image: Paul Tahon/R&E Bouroullec) This “rough quality” can be seen in the Steelwood chair. It’s an elegant rendition of something that might have been knocked together in a farm: wooden legs and a seat held together by a steel frame, like a shovel blade fixed to its shaft. This rural pragmatism explains why Ronan is such a fan of Glenn Murcutt – simple, efficient structures for the vast Australian countryside, not overly refined. “I dislike the very snobbish way of designing,” he says. The brothers’ own foray into architecture, a floating house in 2006, speaks directly to Ronan’s instincts. He needs to escape the city regularly, bolting off to his farm on the Brittany coast or a riverside fisherman’s hut an hour from Paris. “I need to be near the sea, near the water. Erwan is younger than me, and stronger.” Both brothers were influenced by the land art of the 1960s – the first book Ronan ever bought was about Donald Judd’s desert sculptures in Marfa, Texas. He admires sensual modernists like Alvar Aalto and Charlotte Perriand, and the highest quality he can attribute to something is subtlety (“Sometimes [people] are very disappointed when we do a really good work because it is too subtle”). Erwan, meanwhile, actually studied as an artist rather than a designer and was heavily influenced by the American minimalists. His drawings, some of which are pinned to the walls, range from neatly abstract lozenge shapes to fantastical sketches of animals. One of these (which the brothers sent to icon as an impromptu manifesto two years ago) depicts a city taking shape around a sleeping dog. “I’m reading a lot of science fiction books and also fantasies from the Middle Ages, and there are a lot of magical animals that arise in these stories,” says Erwan. “I had this idea of a gigantic animal that would sleep and the city would grow onto the animal, of course respecting it, trying to keep the animal alive. Now we are no more surrounded by animals.” “Just pigeons,” smiles Ronan. “And foxes,” adds his brother.

Triple Blacklight for Galerie Kreo, 2008 (image: Paul Tahon/R&E Bouroullec) Being French, the brothers are easily drawn into literary references. “Since months and months we have been trying to find what could be a good easy chair for outdoors – this is huge work. It’s like for a writer to find a certain character. One of my favourite books is The Idiot of Dostoevsky, when you think of how subtle Myshkin is,” says Ronan of the book’s fragile hero. “Sometimes a chair has to be like that, you need to be very subtle and delicate and this delicacy is something very complicated to find.” Looking at his brother, it’s all too tempting to recognise the qualities of a Dostoevsky character, one of his holy fools, a dreamer whose deep eye sockets lend him a slightly tortured soulfulness. As rain starts to fleck the windows and a Eurostar back to London beckons, we return to the topic of what next. It’s clear that the brothers feel they are at the end of one cycle and the beginning of another. In the last year they have started experimenting with new clients like Established & Sons and Japan Brand. But a new challenge is not as simple as a new client. “We have worked for ten years in [furniture] and now we are in a difficult period because it was easier to do a quick chair a couple of years ago,” says Ronan, rather cryptically. “I think in ten years we will be playing in a lot of different playgrounds. I am sure some new question will arrive.”

Ronan, and a Joyn desk divider

Ronan, with working drawings on the wall

Joyn office system for Vitra, 2002

Erwan’s drawing of the dog town

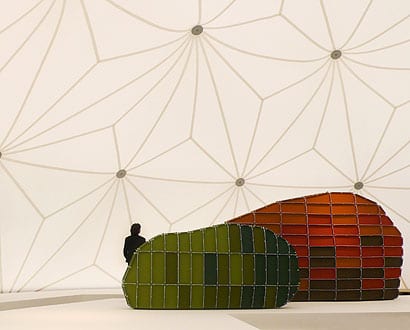

Rocs room dividers for Vitra, 2006 |

Portrait Ola Rindal

Words Justin McGuirk |

|

|

||

|

Floating House, for artists in residence of CNEAI, 2006 (image: Paul Tahon/R&E Bouroullec) |

||