|

|

||

|

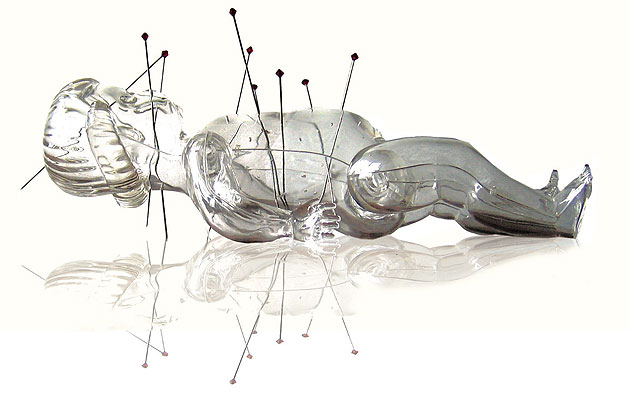

“Contemporary design is still very much a boys’ club,” says Nika Zupanc. “I’m challenging that.” One of the Slovenian designer’s favourite photographs is from Playboy, of design’s leading lights circa 1961. Eero Saarinen, Charles Eames, Harry Bertoia – it’s an all-male group, a collection of dark suits and bald patches. This is the party Zupanc wants to crash. Her weapon is femininity. Her work is a barrage of traditionally “feminine” motifs and objects: dolls, cradles, feather-dusters, frills, bows, flowers. She exhibits in large, stylised doll’s houses. At first glance it’s an onslaught of kitsch. But there’s a political message here, an attack on stereotypes – the question is whether it comes across, or whether it gets drowned out by all the frills and flowers. Zupanc’s earliest work made the message clear. She graduated from the Academy of Fine Arts and Design in Ljubljana, Slovenia’s capital, in 2000. In 2005 she produced a series of malevolent plastic baby dolls. One was pure black with a heart painted on it – not a valentine’s-card heart but a Sacred Heart, with all the blood and thunder of Catholic imagery. Voodoo Doll was pierced by steel needles. It’s passionate, angry stuff, with an obviously ambiguous attitude to femininity and motherhood. After the dolls, she moved to furniture and more functional objects by an appropriate bridge: a cradle. Her first manufactured piece – made under her own brand, La Femme et la Maison, in 2007 – was a feather duster made and packaged like a luxury accessory. It’s typical of Zupanc’s mordant humour. The same year also brought the Maid chair, which has a back shaped like a French maid’s apron, complete with pleated or lace edge. Maid caught the attention of both manufacturer Moroso and the Dutch designer Marcel Wanders, who commissioned Zupanc to work with Moooi. It was Zupanc’s breakthrough – “I was screaming like a teenager,” she says, recalling the moment the email arrived – and a torrent of work followed, a good deal of it following the lead of the Maid chair. The Tailored chair for Moroso has a wasp-waist cinch and the stitching of a corset; the Lolita lamps for Moooi have the bell-shaped curve and lace hem of a child’s dress. We meet in the bar of a Belgrade hotel, a couple of hours after she told the audience at Belgrade Design Week about the 5 O’Clock chairs, her latest piece for Moooi. They are decorated with floral patterns taken from English fine china. Is she concerned that by defining herself through femininity, she risks confining her work to a frilly ghetto and not being taken seriously? “I know I’m walking on the edge by saying that femininity is central to my work, but this is why it’s an intriguing process for me,” Zupanc says. “I am trying to do the opposite. I am trying to take the elements that are considered feminine and to pull them out of the ghetto.” Perhaps uncertain of her English (which is mostly excellent), she speaks carefully and has an earnest air that is quite imposing.

Zupanc’s plan is to take the design language of femininity – the bows, the kitsch, the idioms of dressmaking – and use it in a very rational, functional way. “I try to take these elements to new places,” she says, “to give them a new seriousness. So they could be taken as something that is relevant in the contemporary design.” Take for example the 5 O’Clock chairs. At first glance the floral pattern makes it look like a nostalgic Cath Kidston-style throwback. But ignore the flowers – that black beech frame is sternly modernist, not out of place against the work of the Playboy class of ’61 and Zupanc’s male contemporaries. Or the Modesty sofa, a prim modernist seat with a provocative bow hanging off its back. The bow might seem to be an absurd frippery, but it serves a purpose: the ribbon is threaded through the back of the sofa and is holding the cushions on. If you invest attention in this work, it repays it with interest – there is an appeal to it that raises itself above the trench lines of gender and taste. The wasp-waist of the Tailored chair, the Maid chair’s own “waist” and the neatness of its pleated edges, even that maddening bow at the back of the Modesty sofa – they are obviously more sophisticated, and more attractive, than simple decorative gestures. Zupanc says she carefully weighs the impact her work will have on a man (specifically a man), calling this approach “emotional ergonomics”. She uses the word “seduction”. Would she say that the secret to her design is that it’s sexy? “What I think is more important for me are two things: elegance and a restrained attitude towards those elements,” Zupanc says. “I want to use them but I want to make it painful and very restrained.” Although she does aim to make her products “visually seductive”, she adds: “I think sexiness is a very dangerous word.” It’s not the way she herself would present the work, but she doesn’t reject the description outright: “Maybe you can also see sexiness or something erotic in it but I think you can see that in a lot of things that you adore or like.” If not sexiness, could it be said there’s a note of kinkiness at play here? There’s that tension between seduction and restraint to the point of pain – and some of the pieces have a note of fetishism: the maid’s apron, the corset stitching of the Tailored chair. But Zupanc is surprised by the K-word – “I wouldn’t say that!” – and again says that it’s up for the users to decide. Nevertheless, this emphasis on restraint is clearly important. Zupanc repeatedly brings up, and dismisses, the modernist dictum “form follows function”. But a kind of modernist rigour underwrites her design. Some of Zupanc’s pieces are reminiscent of the limited-edition fantasies of the recent bout of “narrative design” – her giant doll’s houses for Superstudio Piu, for instance, suggest the grandiose whimsy of Studio Job. But although her work is full of storytelling, she rejects the luxury and opulence of narrative design. “I’m actually trying to introduce a quite difficult way of living,” she says. “I’m trying to introduce new values like modesty, strength, attitude – I think these are actually sexy values but in a way they are forgotten.” She gives the example of the Modesty sofa, which is actually not hugely comfortable. “We stop thinking if we are very comfortable all the time.” Discomfort, pain, have been elements in her work since the bayoneted babies, and the intent is political. Zupanc had herself photographed alongside that first collection as a kind of visual manifesto. In the photo, she is glamorously dressed, wearing a tight leather skirt and deadly spike heels – but she is supported by crutches and snarling at the camera in an expression that could be pain or anger. “[I wanted] to explain my attitude towards the constructed, cliched roles of women in society,” she says. “What I was trying to say with this picture was that if you want to play by these rules you are damaged in many senses.” The discomfort, restraint and curious blend of luxurious symbols with ascetic reality – an uncomfortable sofa with a big bow on the back – are an attempt to express what it is to be female. The message is reinforced by the literary references in Zupanc’s work: Gone with the Wind, Lolita, Mrs Dalloway – characters like Virginia Woolf’s Mrs Dalloway “are very good illustrations of the painful situation of the constructed role of a woman in a contemporary society”, says Zupanc. It’s striking, then, that although the words “feminine” and “femininity” litter our conversations, the word “feminist” is absent. Would she call herself a feminist? “No, I am not a feminist, but I believe and fight for the right to express values that do not derive from rationalism, tehnicism, pure utilitarianism and low-key comfort, the ideas that are still dominating design,” she says. “Maybe there is a dimension of feminism in my work. I am in a way in rebellion – this is the thing that drives me on, trying to push things forward or trying to make people think.” |

Words Will Wiles

Image Fulvio Grisoni |

|

|

||

|

|

||