|

Tick tock, tick tock, tick tock. The incessant ticking of the wall clock fills the Paris apartment every time the conversation goes quiet, as if it’s reminding Inga Sempé that time is running out. Tick tock, tick tock, tick tock. The incessant ticking of the wall clock fills the Paris apartment every time the conversation goes quiet, as if it’s reminding Inga Sempé that time is running out. “It is driving Eléonore crazy,” says Sempé, referring to her suffering assistant. “She has even tried to put old chewing gum in it to shut it up.” The Milan furniture fair is less than a month away and the Parisian designer still hasn’t finished her wall clock for French manufacturer Moustache. For some reason the design doesn’t seem to be coming together. The slightly distorted circular shape isn’t quite right and Sempé is experimenting with a pattern for the pendulum, which shows through a cut-out at six o’clock. “I have to be happy with the end result because otherwise I don’t want to present it,” says Sempé, but she doesn’t seem stressed. Instead she carelessly chats the afternoon away as if she has all the time in the world, but it’s all a deception. “In fact I’m hyper stressed but I learned a long time ago to look calm,” says Sempé in her deadpan fashion. “I think I deserve an Oscar, but I don’t sleep at night, all the projects come into my mind when I try to sleep.” Inga Sempé is a designer of extraordinary sensibility. She adds feeling to the driest objects, such as clocks and wall lights, creating visual poetry along the way. Take the totemic Brosse shelves for Edra, from 2003, where the simplest of aluminium structures is given a fringe of the kind of bristles that brooms have, making an almost mythical object where your belongings can hide. Or the recent W103 task light for Wästberg with its elegant inverted clamp held in place by the stem itself. Her pieces are pleasurable to look at without trying to be decorative; they solve problems in an inventive and highly lyrical way. She is like a detective of the everyday, studying and lifting details from the world around her and inserting them into her work. Inga Sempé has been touted as the next big thing for almost a decade (she set up her own practice in 2000 after working for Marc Newson and Andrée Putman), but curiously her name isn’t as widely recognised as those of her contemporaries the Bouroullecs and Konstantin Grcic. In fact, Sempé seems to actively work against that kind of recognition. She doesn’t have a PR machine working for her, she answers her own emails and picks up the phone herself. It doesn’t interest her to be a name or a face of design, she doesn’t care about being in museum collections. “My aim was always to have my objects in the shops, to be part of the movement of life, not in museums,” says Sempé. “Design in this country is not connected to quality of life but the personality of designers. It’s seeing design in a fake way, it’s closer to haute couture.” So can Inga Sempé put them straight? We have just finished lunch at the neighbourhood restaurant. Sempé has kept her coat and scarf on throughout and sits at an angle that doesn’t make her look altogether comfortable, but the conversation flows easily and often strays into personal territory (Sempé loves real life stories and reads a lot of autobiographies in her spare time). The restaurant is tiny with rickety tables and chairs. Old wine bottles line the walls. It has a rough and undesigned quality which goes well with Sempé’s preoccupation with the “everyday”. She studies it with an insatiable appetite – on the street where she lives, in hardware stores. On the way back to her studio she points out the dream location for her practice – a corner shop currently occupied by a cobbler. “I really like daily life, that’s why I would like to have a studio on the street,” muses Sempe. “You open it on Monday morning and close it on Friday evening, like life in a Jacques Demy film. I like to be like everybody else.” Sempé likes to de-dramatise the design profession. It’s as if her reason for being a designer is to break down the pedestals we often put them on. “I’m more like a doctor’s secretary when I work,” she says, describing just how normal her day to day is. But there is nothing doctor-like about her practice; if there once was, it’s now more like a doctor’s surgery gone bad. Her studio is a mess of miniature models, scraps of paper, dusty filing cabinets and mismatched furniture. It’s located in the living room of her apartment, which is almost completely empty of design. There is a dead and undecorated Christmas tree in one corner (it’s March), bare light bulbs hang from stiff wires in the ceiling and a baby stroller blocks the hallway. “I don’t like to buy design objects,” explains Inga. “I prefer the flea market. I have a huge visual culture from the flea market but I have a really low culture of knowing names of designers and companies.” As her home is the setting in which most of her objects are created it’s tempting to make a connection between that and the fact that her designs often take the mundane materials of the every day as their starting point. Paper in the case of the Vapeur lamp for Moustache; simple cotton fabric for the Armoire Suple cabinet, also for Moustache; a duvet for the Ruché sofa for French furniture manufacturer Ligne Roset. The pleated texture of her first two designs for Moustache made them the stand-out pieces at its debut in Milan last year. Again, Sempé managed to solve a problem in an extraordinarily beautiful way. In the case of both Vapeur and Armoire Suple, pleats were the solution to flat-packing pieces in order to make them easier and cheaper to produce and to transport. But they have none of the formulaic look of flatpacks. Unfolded, the pieces take on unexpected and beautiful shapes. “I love the mechanic quality of pleats and I’m fascinated by how pleats completely transform a material and change its shape and texture,” says Sempé. “It has nothing to do with fashion, even if many people want to interpret it in that way.” The samples for the quilted texture of the Ruché sofa are scattered all over the studio and Sempé is still studying them with interest. It reminds me of seeing her a couple of months earlier at the Ligne Roset stand at Parisian furniture fair Maison & Objet. Then she was visibly relieved that the end result and colour had come out almost like she envisaged it. “I’m not too disappointed,” she says, sinking into the softness of the quilted fabric. It’s possibly this critical response that has earned her a reputation as a “difficult” designer, but that doesn’t bother her in the least. “You shouldn’t be afraid of being regarded as a pain in the arse,” says Sempé. “Otherwise you just get swallowed up by manufacturers and PRs.” There is certainly a difficult streak to Sempé. It’s hard to work her out. She can come out with something really provocative while looking demure, she isn’t bothered by long silences and the informal chattiness over lunch is now replaced by a certain awkwardness. It’s difficult to talk to Sempé without feeling self-conscious. “But I’m afraid that I’m not as difficult as I should be. I’m still an angel at work in comparison to how I am in my personal life,” she says.

W103 task light for Wästberg Because of the way that Sempé has set up her studio, her personal life seeps into her daily work. It is, for example, impossible to avoid talking about Sempé’s role as a mother, something that otherwise seldom comes up in interviews. As she clears a chair for me to sit on her two-year old daughter comes in for a quick cuddle and no doubt to check on the foreign visitor. Sempé’s 12-year old son is in school around the corner. “It’s easy to have them around, because I’m easily distracted anyway,” says Sempé. This afternoon the work is interrupted by a phone call from her son’s school. “They would like me to come in and see them,” she says. While she is very open about her children, she doesn’t even mention her partner, Ronan Bouroullec. The only sign of him here is the Steelwood chair the Bouroullecs designed for Magis next to her desk and a magnet with his name on it, stuck to the shade of a black Ikea task light. So how does she get the job done in this domestic setting and what does it involve exactly? In-depth product research is the first step. “Everything looks very boring to me until you start to research around it,” says Sempé. “It’s normally not the object that is boring but the framework around it.” She means the process of making it, of reaching the end result. Even if designing by nature is a collaborative effort, with manufacturers, marketeers and the end user, Sempé sees designing as a solitary pursuit. “I don’t know if I would be happy working with so many people all the time.” In the studio, she has two assistants helping her, she calls them her children and they produce all her miniature models. “Before we got the paper for the Vapeur lamp, Eléonore folded paper all day long,” says Sempé. Sempé doesn’t make models anymore and she only draws by hand when she absolutely has to. “There is nothing pleasurable about drawing for me,” says Sempé. Possibly it’s the side effect of having artist parents (the famous illustrator JJ Sempé and children’s book illustrator Mette Ivers-Sempé) that has made it more of a chore than relaxation. “I only use it as a means of explaining an idea, as a means of communication.” Her artistic parents had very little to do with her decision to become a designer. “It’s funny because my parents must have been part of one of the most cultured communities in the world and still none of them seemed to connect the objects surrounding us to designers. It was as if they had always been there – spoons and bugs in the same drawer.” However, this way of looking at design seems to influence her view of her profession. Her work as a designer is an effort to remove the boundaries between the designer and the public, even to the extent that she wants her studio at street level. So is there an element of wanting to educate people about design and the work of a designer? “Oh no!” exclaims Sempé. “I’m doing this only for myself.”

Moët armchair for Ligne Roset, 2007

Digital and Analogue clock for VIA, 2000

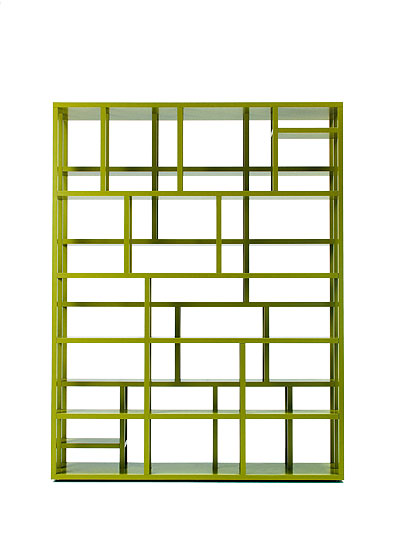

Double Access shelves for David Design, 2008

Suitcase in three parts for VIA, 2007

Prototypes of the Vapeur lamp for moustache |

Image Ola Rindal

Words Johanna Agerman |

|

|

||

|

Brosse shelves for Edra, 2003 |

||