What if fashion could capture carbon instead of being a major contributor to the world’s emissions? Post Carbon Lab designer DJ Lin explains the studio’s research into algae-based textiles

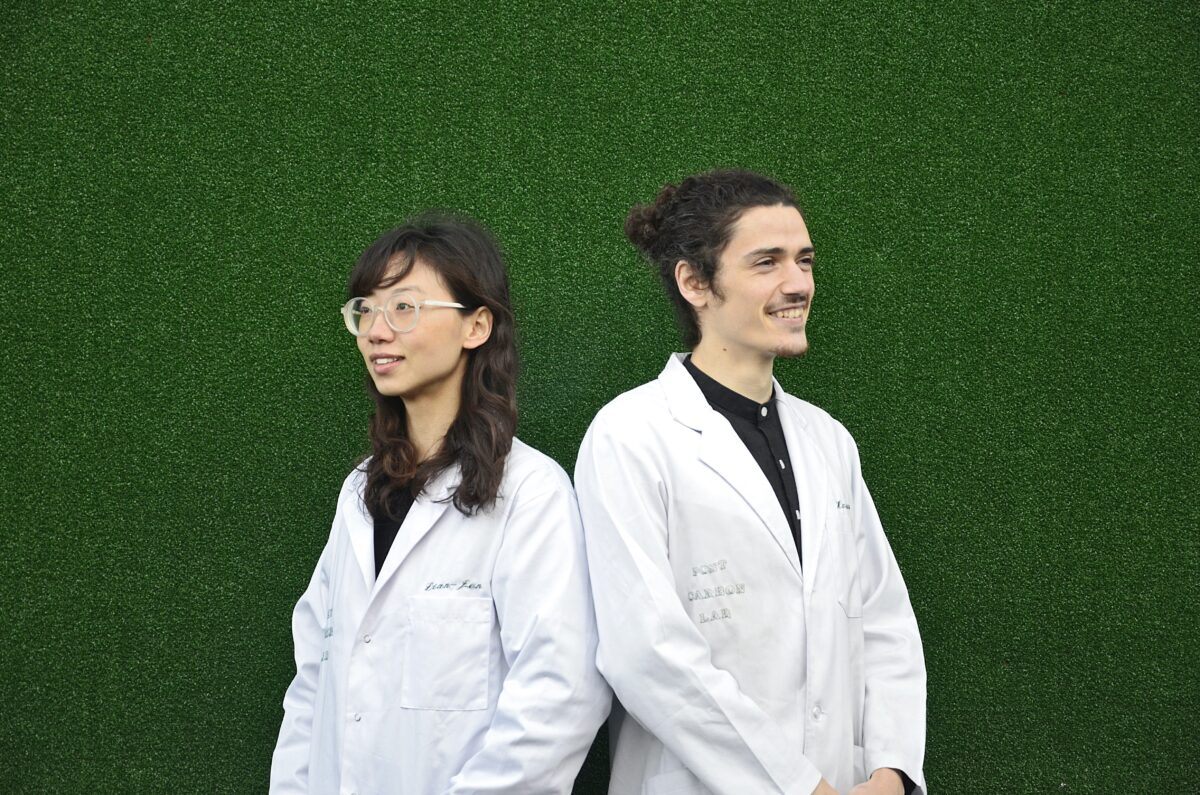

Photography courtesy of Post Carbon Lab

Photography courtesy of Post Carbon Lab

Words by Flo Wales Bonner

While the fashion industry continues to be among the world’s most polluting, a growing number of projects and organisations are emerging to help mitigate – or even reverse – its harmful effects.

One area of exploration is carbon-capturing clothing, in which textiles are activated with microbial treatments and coatings derived from algae in order to actively draw carbon from the air during wear and in turn produce oxygen.

In recent years, designers including Charlotte McCurdy from the US and Canadian-Iranian Roya Aghighi have made headlines after creating clothing using algae-based textiles.

Photography courtesy of Post Carbon Lab

Photography courtesy of Post Carbon Lab

But one of the pre-eminent forces working in the area is London-based transdisciplinary design lab, research studio and social enterprise Post Carbon Lab.

It was co-founded in 2020 by Taiwanese Dian-Jen (DJ) Lin, a designer who has been experimenting with photosynthetic textiles since 2014, and Belgian architecture graduate Hannes Hulstaert, who uses his training to construct the lab’s facilities from salvaged and recycled materials.

Post Carbon Lab regularly collaborates with organisations in the fashion space – recently creating garments for Alexander McQueen line McQ and Pakistani brand Azgard9 – but, says Lin, it is currently exploring leads from companies in sectors ranging from interiors to product design to cars. She told us more about the company’s future-forward work.

How were you inspired to enter the world of sustainability?

When I was working with famous high street and luxury fashion brands around a decade ago, there was no consideration for sustainability. We were using some pretty drastic methods to destroy samples and accessories on a seasonal basis.

And then on top of that, if you were to visit the suppliers, they wouldn’t be working in the finest conditions – eating their lunch in front of the sewing machine, surrounded by industrial fumes. It was just obvious to me that nobody involved in the industry I was exposed to at the time was happy; there was no care for mental health, people were overworked.

That changed things for me. I started working to find an answer to the question: what is the ecological role of fashion and what is the social role of fashion? All modern human civilisations wear some sort of covering so garments, clothing are omnipresent.

And we know that the textile industry contributes to 10% of humanity’s carbon emissions as well as 20% of the world’s water pollution. So I thought, what if that impact could be reversed and could be contributing to something regenerative and positive? That’s where things started.

Photography courtesy of Post Carbon Lab

Photography courtesy of Post Carbon Lab

How did you move from that realisation to working with algae?

There’s a whole subculture of people doing textile farming, and from 2014, while still working in fashion, I started experimenting with all different kinds of photosynthetic organisms like lichen, seeds and plants, as a hobby.

Then in 2017, I had the chance to work with the Natural History Museum, exploring the most fundamental photosynthetic microorganisms. The further you move down the tree of life, the lesser an organism’s maintenance and demand for a complex, nutritious environment becomes.

So we started working with blue-green algae in that way, because it proved to be much, much easier to work with than the other organisms. That’s where the research and development around its potential with photosynthetic textiles began.

How do the textile applications you create work?

Basically, we embed microorganisms into the fibres of textiles, which then gives them photosynthetic properties. But for the treated pieces to stay photosynthetic, they require air and moisture.

It forms a symbiosis: you feed the plants, the garments, and then the plants contribute their fresh oxygen back to you, so if you were to wear it or have it in your domestic environment, it would be able to mitigate your carbon footprint.

As a rough guideline we say that on the surface area of a lightweight, small-to-medium-sized cotton jersey T-shirt, the photosynthetic properties are similar to those of a young tree.

Photography courtesy of Post Carbon Lab

Photography courtesy of Post Carbon Lab

Can you explain the concept of regenerative sustainability activism that guides Post Carbon Lab’s work?

What ‘sustainable’ tends to mean is just that we’re able to continue doing what we want to do to the planet and for it to still be manageably convenient. But then over the past couple of years, people have started talking about the regenerative element, asking: what about the wrongs that we’ve done in the past?

Regenerative sustainability touches on that, where we’re pursuing more than reaching just zero [carbon], and moving towards restoring and replenishing.

So the concept of regenerative sustainability activism explores the actions we can take to embed this ideology into a broader context that’s going to maybe unconsciously influence people’s behaviour and buying decisions or allow them to reframe their current relationship with fashion – for instance by wearing clothes with a photosynthetic coating.

How have you seen fast fashion influence people’s relationship with their clothing?

I was in Oxford Circus, where there’s a really big Primark. I saw a woman carrying maybe six of their big paper shopping bags. It was a rainy day, and she didn’t have an umbrella.

She was walking down the street and one of the bags fell on the floor, soaked in the rain. She was like, ‘oh, okay’, and just kept on walking. She didn’t bother to pick anything up. That’s our mentality with fashion at the moment.

Fast fashion tells us that whatever we want, we get, and then we do whatever we want with it. It’s problematic. I think a lot of the businesses trying to be more sustainable don’t necessarily address the consumption issue.

Photography courtesy of Post Carbon Lab

Photography courtesy of Post Carbon Lab

On that topic, talk to me about your project Design Nudges for Sustainable Consumption, where you redesigned plastic water bottles to encourage more conscious buying decisions.

For this project, we looked at PET-bottled water, and how, in places like Europe and the UK where tap water is drinkable, what’s the point of it? It’s just contributing to more plastic consumption.

So we made several different hacks to the graphic design surrounding a classic bottle of water, to investigate – along with a neuroscientist and a psychology consultant – which type of sustainability communication would work best in terms of encouraging people not to buy things.

Our favourite design is one with an entirely black bottle with a thermochromic coloration. You have to use your body heat to warm it up in order to see the label and tell whether you’re buying orange juice, bottled water, soy sauce, or whatever.

You’re actually embodying your heat onto the packaging, you see your hand print on the bottle, and it’s our way to kind of nudge users to interact with the object in an almost intimate way and take time to decide, do I really need it?

What other projects are you inspired by in the carbon-capturing space?

I think trees get a little bit too much credit for photosynthesis – 80% of our oxygen is actually provided by the ocean’s photosynthetic plants and planktons.

But many of these organisms that are meant to do the carbon-capturing job for us can’t because the ocean has simply become too polluted, warm or acidic for them.

So there are groups and initiatives – including one called Project Seagrass – that are restoring them, farming aquatic plants in smart ways and applying permaculture methods to the ocean world. It’s fascinating.

Photography courtesy of Post Carbon Lab

Photography courtesy of Post Carbon Lab

What’s your dream for the future?

To take Post Carbon Lab to a completely different cultural context, and franchise in India or other countries that are the direct receivers of the impacts of climate change. We’d love to work with local enterprises and contribute to the betterment of the local microclimate.

As to my broader vision, it would be for us all to take care of our own carbon calculations on a daily basis. So when you’re at work you’re like, okay, I’ve been working on a laptop for five hours today. That means this much carbon footprint, and it’s my responsibility to mitigate that through any means that I can.

I’d also like to see that when a product is launched in, say, a high street store, its carbon footprint is reflected in the price point. That’s my ideal vision. Of a future where everybody’s own little carbon mess is managed.

Get a curated collection of design and architecture news in your inbox by signing up to our ICON Weekly newsletter