It’s not every day a design icon releases something new—especially not 44 years after his death. But in late 2024, the long-shelved PK23 chair by Poul Kjærholm, one of Denmark’s most revered modernists, was quietly introduced by Fritz Hansen to mark the 70th anniversary of his first furniture design. Equal parts minimal and masterful, the PK23 isn’t just a new addition to the canon. It’s a reminder that great design doesn’t expire: it simply waits for the right time to be seen

Photography courtesy of Fritz Hansen

Photography courtesy of Fritz Hansen

Words by Emily Nathan

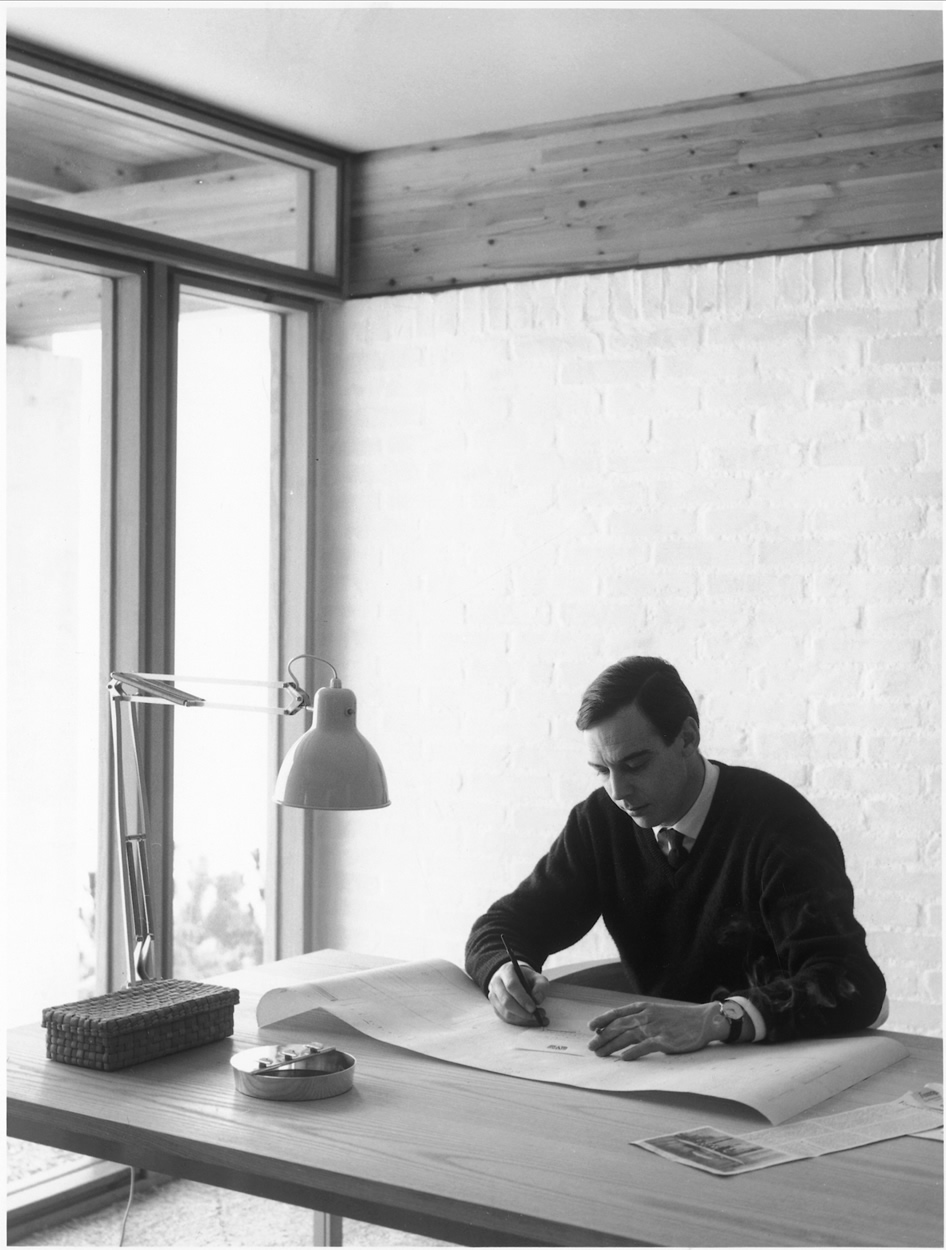

Originally conceived in the late 1970s but never brought to market, the PK23 has a strange and surprising history. It was one of the last designs Kjærholm developed before his untimely death in 1980, just shy of his 50th birthday. After he passed, his long-time collaborator Ejvind Kold Christensen decided he didn’t want to continue without him.

“He realised there wouldn’t be any more designs from Poul… and he didn’t want to go on without his creative partner,” explains Michael Sheridan, an expert in Nordic architecture. Instead, Christensen sold the rights to Fritz Hansen—“bringing Kjærholm home.”

Photography courtesy of Fritz Hansen

Photography courtesy of Fritz Hansen

Known for his minimalist, material-driven approach, Kjaerholm saw furniture not as ornament but as architecture in micro. Where others might chase form or flourish, he sought to reveal the essence of materials: cool steel, warm wood, woven textile. “I’d rather express the character of the materials than my own personality,” he once said. The PK23, with its refined interplay of steel and woven surfaces, is a quiet embodiment of that ethos—restrained, rational, and strikingly human.

At the time of transfer, not everyone at Fritz Hansen saw the vision. “It’s half handicraft,” one design director protested. “It’s too damned expensive. It’s alien to us.” But the board overruled him: Kjærholm’s work was not about production scale; it was about uncompromising quality.

That tension—between industry and intimacy, permanence and impermanence—is what gives the PK23 its quiet gravity. It’s furniture that exists in and of itself, “without style” in Sheridan’s words. And while in today’s culture of branding and signatures, this idea might feel radical, Kjærholm always believed his work should transcend trends, existing on their own terms, like the trees and the sea and the landscape.

Photography courtesy of Fritz Hansen

Photography courtesy of Fritz Hansen

The chair’s release comes at a moment when design culture is once again turning toward authenticity and tactility, and Kjærholm’s work offers all three. His output was limited, precise, and deeply architectural. Every element stood alone but worked together—a philosophy mirrored in his deep connection to the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, where his furniture and architectural thinking helped shape the museum’s identity.

When Louisiana first opened, its founders invited Denmark’s leading designers to be part of the experience—not just to furnish it, but to embed design into its DNA. A Kjærholm sofa still greets visitors in the first gallery, setting the tone for an institution that understands art, architecture, and furniture as one continuous expression. The concert hall chairs he created for the museum are a prime example: designed with an open weave to account for sound absorption, their structure is as much about function as it is about form.

Photography courtesy of Fritz Hansen

Photography courtesy of Fritz Hansen

Such holistic vision extended into Kjærholm’s private life. His family home, a square 15x15m layout with a clean, pine-paneled interior and a view to the sea, remains today just as he designed it, down to the last chair. Almost all the furniture was his, and the space is still inhabited by his son and daughter-in-law. To this day, even small modifications require approval, to preserve the home’s status as a modernist landmark.

Ultimately, the PK23 chair is less a “new” chair than a rediscovery of an unfinished sentence—one that now feels more relevant than ever. It shows us that the future of furniture design isn’t about reinvention, but resonance. And who better to teach that lesson than Kjærholm, who wasn’t designing for fashion, but for permanence.

Get a curated collection of design and architecture news in your inbox by signing up to our ICON Weekly newsletter