|

Peter Marigold is looking for a tree. We are on Hampstead Heath, north London, and he is searching for the fallen tree that has provided material for his designs for the past four years. But it’s gone, finally removed by the council. Maybe it’s just as well. “I’m actually not that much of a fan of wood,” says Marigold. It’s a strange thing for the 34-year-old designer to say because so much of his short career has been spent working with wood. And not simply as a material – wood’s unique properties have generated the form of many of his pieces, from the split branches of the Split boxes to the thin-sliced eucalyptus of the Thin Slice cabinet. It even creeps into projects that don’t use it as a material, such as Pied de Biche, a metal shelving unit – with feet reshaped to resemble carved wood. So, if he’s not a big fan of wood, why all the wood? “It’s just so easy to work with compared to metal or plastic,” Marigold says. “And I live next to this huge source of materials – if I lived next to a scrap yard I’d probably be more into metal.” It’s a laid-back thing to say, and Marigold comes across as being a pretty laid-back guy. But this relaxed demeanour is coupled with a restless drive and a demanding work ethic. Marigold says he works 12-hour days six or seven days a week. In just three years, he has become a prolific presence on the London design scene, one of a new generation of designer-makers poised to become major figures. Newly named as one of the 2009 Design Miami Designers of the Future, after his trip to the park with icon he was heading to Art Basel to build an installation alongside his fellow winners – Raw-Edges, Nacho Carbonell and Tomáš Gabzdil Libertiny. Marigold came to design only recently. He graduated from London’s Royal College of Art in 2006, winning acclaim for an ingenious wedge-shaped shelving system so simple that it was hard to believe no one had thought of it already. But before the RCA, he had spent a decade as a sculptor and set-builder.

Tan mirror, 2008 (image: Luke Hayes) The designer is strikingly dismissive about his time as a sculptor. To him, it’s an aberration, a false start, not part of his background. “When I was a kid, I really wanted to do product design,” he says when we settle in a Hampstead pub after the walk. “I just got lost along the way, and was pushed to go into sculpture.” The RCA was the best thing that ever happened to him, he says, freeing him from fine art. With that in mind, it’s not surprising that he has spent his time since graduating in the company of his former classmates, as part of the loose design collective Okay Studio. The reasons for Marigold’s disillusionment with art throw light on him as a designer. “What I see in a lot of art is people trying to make ‘art’ instead of trying to make things that interest them,” he says. For Marigold, the conceptual dimension of art was cluttering his work – craft, by contrast, offered simplicity and honesty. But that has more to do with Marigold as a person than art as a pursuit – he has an intensity and a nervous energy about him, and says he can be quite obsessive in his work. Ideas stick with him, and you can see how he might easily find himself bogged down in brooding on conceptual details. So he strives to escape from that trap. Talking with Marigold, the key words are “direct” and “immediate”. His entire practice as a designer is an effort to remove all obstacles between an idea and its physical reality – to get something out in the world as quickly as possible. His ultimate ambition appears to be to design almost purely on instinct: “I’m extremely fatalistic, and I’m quite interested in how your body and your brain are creating things without you having control over them.” It’s this fixation that has led him to use wood so often – “it’s just so immediate” – and what gives much of his work a quality of honesty and rawness. Marigold’s SUM shelving units, produced by British furniture maker SCP, have the lingering aesthetic of the fruit & veg boxes that inspired the project. Like the Thin Slice dresser and the Yield screen for Libby Sellers, from a distance they look like they might give you a splinter. (They won’t.) And those are the finished pieces, ready for gallery or furniture store. The experimental work is even more stripped down. One of Marigold’s earliest pieces, a student project called Prop, is a stick that is used to prop boxes up out of reach. It’s an idea of inspiring simplicity and purity. And it’s the perfect example of Marigold’s design ethos: to make things that are “good enough”, not over-engineered or over-thought. “If you look at nature, it’s no better than it needs to be,” Marigold says.

Hannah wardrobe from the Palindrome series for Art Basel, with plaster “animal head” to the right, 2009 Nature comes up often when talking with Marigold. A lot of his work is involved with exploring the patterns and laws found in the natural world, revealing order in apparent disorder. The Split series and its offshoots, for instance, exploited the fact that splitting a branch any four ways will still create four corners that add up to 360 degrees. His installation for Art Basel explores symmetry, a phenomenon “we think of as normal and yet it’s completely bizarre.” Part of the installation consists of plaster blobs mounted on mirrors – reflected, they resemble animal heads, like a 3D Rorschach test. The new series of furniture he designed for Basel, called Palindrome, also plays on symmetry. Half of each piece is glass fibre-reinforced acrylic resin formed inside a wooden mould. After this half is made, the mould is dismantled, slightly re-cut and reassembled “inside out” to make the other half. This is Marigold in his element: “I was working immediately with the material, and the pieces are all dictated by the size of the planks of wood that I’m using, they’re quite architectural, blocky pieces and they’ve got wood grain on them … and for me these are my favourite pieces at the moment.” This hands-on relationship with ideas and materials explains Marigold’s long hours. He defines himself as a maker as much as a designer, and says he finds it difficult to delegate. “I’m very edgy about letting other people actually build my stuff,” he says. “When it comes to finished objects, I find I fall out of love with it a bit if I didn’t make it. That’s kind of the curse of making things yourself.” But isn’t delegating to a manufacturer the definition of design? There’s still a lot of sculptor in him. Another characteristic of Marigold’s work is his unusual combination of tenacity and impatience. One of his most appealing traits as a designer is that he sticks with concepts, continually altering and developing them as they recur in different projects – the principles of the Split series of boxes, for instance, have made an appearance in half a dozen Marigold pieces. But once an individual piece has been made real, he wants to move on without finessing the details. “Sometimes I can’t wait to get rid of them, and get them out of the door,” he says. “I’m really not interested in highly finished products.” When a Marigold piece is over-finished, what it gains in craftsmanship it loses in verve. An example is Octave, the first series of one-offs he produced for Libby Sellers when he was signed by her nascent gallery in 2007. The Split principle is here applied to long, thin branches, in theory making a sinuous freestanding shelving unit. But the result isn’t very successful – a ricketiness that could be endearing in a less finished piece becomes uncomfortable when married with fussy details such as the guitar marquetry on the shelves. Subsequent Marigold pieces for Sellers have been able to keep the spontaneity of the designer’s thought processes. Similarly, he is not continually fine-tuning his work with an eye to mass production. “I’m just too busy to bother changing my style to fit a company,” Marigold says. “I think it’s more interesting if a company has the intelligence to say ‘we can change this into something that fits our company’.” This was how it worked with SCP, he says, but he does find it difficult to surrender even part of his total control over an idea.

Octave, one-off for Libby Seller, 2009 But part of his reluctance to tailor work to manufacturers may stem from frustration with the role designers are expected to play. He is gloomy about the prospects faced by young designers – even given his relative success in both the gallery and the factory, it can be difficult for him to make ends meet. And he deplores a culture in which designers are often expected to work for nothing. “Product designers give away ideas for free, and they generate more and more and more, and it’s very insulting,” he complains. “I think the reason there’s so much objection to ‘design art’ is that some companies are actually getting scared that designers are waking up and realising that their stuff is actually worth something to someone.” Where does he see himself in the future? He laughs, and says he doesn’t have any plans beyond fixing his flat, the roof of which is leaking again. Returning from the heath, icon sneaked a look inside the flat, which he shares with his partner and a giant snail called Marvin. It’s a little cluttered, filled with collections of oddities – a wall display of broken wing mirrors, small boxes of natural objects such as crab shells. This hoarding instinct explains another recurring theme of Marigold’s work: his interest in shelving and storage space. “I’m always thinking about putting things on surfaces,” he says. The act of making, for Marigold, is a way of ordering the internal world, as well as the home. It’s that nervous energy again, bubbling away, urgently needing an outlet. Designing a new piece opens “the possibility of taking more of my junk and putting it on shelves”, he explains. “And that represents something about how my mind works, this kind of accumulation of information and junk over time.”

Slip table for Dovetusai, 2009

Pied de Biche for Libby Sellers, 2008

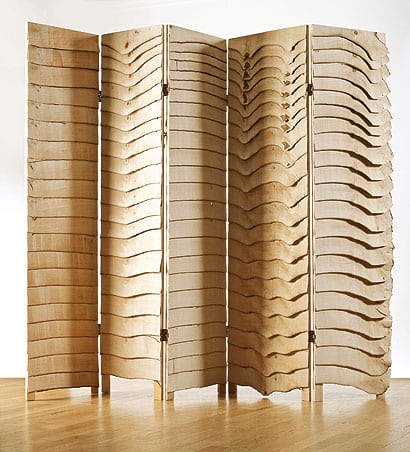

Yield screen for Libby Sellers, 2009 (image: Courtesy Gallery Libby Sellers)

Prop, 2006

Toy shelves, 2009 |

Portrait Jo Metson Scott

Words William Wiles |

|

|