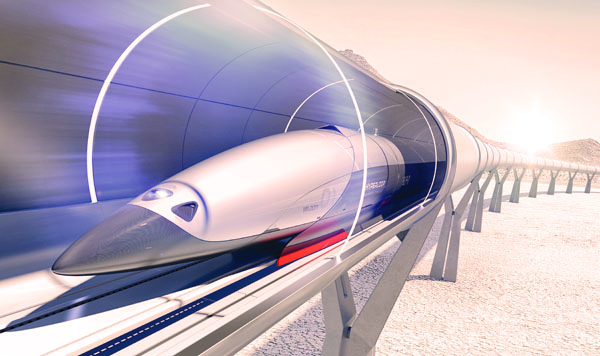

Render of the Hyperloop’s Maglev capsule in its low-pressure tube

From airline interiors to driverless tubes, and now the sleek capsules for Elon Musk’s Hyperloop, Paul Priestman has made it his life’s work to move people more quickly, efficiently and comfortably. Icon spoke to the high priest of global transport design

By John Jervis

With the exception of Jony Ive, Paul Priestman is the most successful British designer at work today. His rise from a single ceramics O-level, via Central St Martins and the Royal College of Art, to his current status as the head honcho of global transport design, has been meteoric, no question. At this year’s London Design Festival, he was anointed with the ‘design innovation’ gong at the British Land Celebration of Design, with accompanying hosannas: ‘From the new Tube for London to airplanes and hotels, his visionary thinking has shaped daily life for millions of people around the world.’

As chairman of London design studio PriestmanGoode, that’s pretty much true. On top of such accolades, he’s also sensible, considered, genial, almost paternal. So much so that, when meeting Priestman at the firm’s offices in Fitzrovia – a location selected for its gilt-edged clients, for whom centrality and style are the norm – my hope is to push a bit, diverting him from rehearsed lines about the pitch of airline seats and into more personal areas, and possibly even elicit some irritation.

We’re here to look at the firm’s capsule designs for Elon Musk’s Hyperloop, launched at this year’s LDF. Priestman met CEO Dirk Ahlborn at a dinner in Dubai two years ago. Ahlborn admired the firm’s back catalogue and, after some flirtation,‘eventually was prepared to pay for us to do some work’. Priestman is attracted by the mixture of uncharted and familiar in Hyperloop. ‘Unlike every other form of transport, it’s a completely controlled environment – there’s no weather, there’s no cows wandering onto tracks – but it’s all existing technology. The Maglev capsule is an aeroplane. All you’re doing is putting it in a reduced atmosphere, reducing friction – it’s equivalent to an aircraft travelling at 38,000ft, with all the pressure tests that requires.’ The result is sleek, glamorous, and looks, to my eyes, a little like Concorde. Priestman goes further: ‘It’s like a spaceship. We didn’t want it to look like a train because it’s not a train, it’s a floating capsule, so it’s got an autonomous feel to it.’

PriestmanGoode’s pre-eminence in the airline market is acknowledged, progressing from interiors for Virgin in the late 1990s, via much admired work on the Airbus 380, to any number of national carriers: Swissair, Emirates, Lufthansa, Thai, United, Qatar, Air France. Much of this work is handled by co-directors Luke Hawes and Nigel Goode – Priestman’s heart really lies in trains. And, despite the visceral thrill he still gets from their exteriors – their split lines and contours – he can be equally evangelical about advances inside. Talking about the new private sleeping pods on Austria’s ÖBB ‘Nightjet’ service, he enthuses, ‘I was interested in what we’re going to do about overcrowding on existing systems. These might get people to travel off-peak, but also stop them crowding into hotels to stay overnight before meetings by getting them to sleep on a train instead.’

This is design-thinking stripped of intellectual flimflam. Similarly, his Scooter for Life for the Design Museum was not just a pleasant mock-up featuring an overly glamorous granny, but a genuine, joined-up effort to make scootering palatable and practical for an ageing demographic, escaping the stigma of mobility scooters and encouraging fitness. And ‘if people can travel further to stations and bus stops, you don’t need to build so many, and you don’t clog up the network’.

Despite his stake in the Elon Musk dream (and his own Tesla is ‘absolutely brilliant, absolutely amazing’), he is far from a future of travel fantasist. Driverless cars? ‘Everyone is hyping them, but Mr Whatshisname in his old Jag, are you going to tell him not to drive his car? Guys in America, in Texas, when they hear us talking about the end of the car, they just laugh … The car I have drives itself, it keeps itself in the lane, but I still take up as much space, and that’s the problem. Until we get to the point where people are sharing properly, it’s not going to solve anything.’

I ask him why the car industry seems so insular, so unengaged with the wider design world, and he replies, ‘I think it’s finally beginning to wake up, but cars are still designed for personal ownership, not for shared use, and I think they’re stuck in that rut. And the adverts you see on TV are a complete fallacy – driving through streets with no cars, parking outside the restaurant and wandering in … If you did an advert for public transport like that you’d be strung up.’

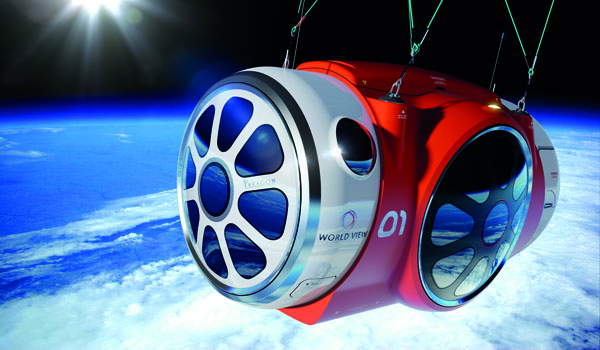

Render of World View capsule, to be lifted by helium balloon into space, designed for Paragon in 2013

He’s canny as well as talented. Priestman must be one of the few outsiders to rise to become creative director of a Chinese firm, the rolling-stock manufacturer CRRC Sifang in Qingdao: ‘I’ve been to the same hotel there nearly 50 times – it’s a week of my time to get there and back, so that’s a whole year of my life.’

For once, he sounds slightly weary. He first visited China as a student in the late 1980s, and finds the disappearance of the ‘sea of bicycles’ sad, but ‘I’ve always loved the people, and their ethos about putting friendship before business.’ He praises the quality of the executives – ‘They’ve worked their way through a company, and have to reapply for their jobs every four years’ – contrasting this to experiences here, where ‘the guy at the top is totally out of touch and seems to do nothing at all’. However, PriestmanGoode’s magnificent designs for China’s new high-speed train are downplayed in the firm’s publicity: ‘The one thing they are sensitive about is that this train is an image of modern China, and for us as British designers to jump up and down and say we designed it would be unhelpful. This is used by the Chinese government, and they’re very proud of it – rightly so.’ The deterioration of the human-rights situation doesn’t get a mention.

When asked how the design industry has changed over his career, he is frank: ‘It will be interesting to see what happens to design consultancy in the future, given the demise of product design – products are devalued, they have become disposable … When I started off, we would have people phoning up and saying, “Could you design a washing machine for us please?” Now retailers travel to a place in the Far East, look at all the designs, and say, “I’ll have a bit of that one, and a bit of this”, and it will cost them nothing.’

With firms such as Apple and Samsung keeping design firmly in-house, he’s been lucky, and prescient, to end up in transport – and he still loves it, even if progress can be ‘ridiculously slow’. His frustration that, two years on, the firm’s high-density Horizon seating for trains, funded by the Department for Transport, has yet to reach production is palpable: ‘Everybody loves it, everybody wants it, we just need one car on a train somewhere to try it.’

Render of the New Tube for London, designed for Transport for London in 2014

I ask him if he misses the immediacy of his early years in product design. ‘Designing for the Italian furniture industry, that whole glamour: they don’t pay. It’s royalty-based and you’d be very lucky if you make any money. I never wanted to be a furniture maker with a few helpers – the design of expensive objects, it never really grabbed me. I much prefer the problem-solving, the innovating, and also the sheer volume of people who experience what we’re doing every day.’ Even so, he still has a workshop at home where he tinkers at weekends – he’s currently working on a commission for some speakers: ‘The nice thing about product design, it’s about the right size to spin around in your head. Trains are a bit more difficult.’

Despite speaking out repeatedly against Brexit, he is quietly confident about PriestmanGoode’s future prospects. They’ve just had their best year ever, and became an employee-owned company in April last year. This decision, Priestman says, ‘just makes me feel good. And anyway, if someone had bought us, and I’d had a finance director plonked next to me, I wouldn’t have lasted five minutes.’ As to that irritation I hoped to elicit, no luck. I’m reduced to asking him what makes him lose his rag: ‘I’m very protective of my designers, I don’t like being messed around, or people taking advantage of us.’ Yes, he really is that much of a gentleman. Before leaving, he takes me out to admire the glazed bricks of the office’s restored Victorian light well, which reaches six storeys up to the bright September sky above. His pleasure in the space – its concept and workmanship – is touching. ‘It’s fantastic, these glazed bricks are lovely. They were clever, weren’t they? It’s just reflective to get the light down.’ It’s a simple space and a simple idea, but it’s beautiful. For Priestman, this is design.

Article by John Jervis