|

|

||

|

The artist has been given the run of Chatsworth House and its 18th-century collections for two shows exploring the use of ornament as power. John Jervis met him in the lead up to their opening at his home in Kent “I think the charm of Deal is …” Pablo Bronstein begins, then peters out. Certainly, the town’s allure for a modern artist is hard to decipher, beyond low property prices at the further reaches of Kent’s railway network – there’s a sense of decay, and of lives lived elsewhere. He tries again: “It’s rather charming, and quite odd. It has a reputation for depravity in 18th-century novels – whenever someone goes by Deal they get a headache.” He’s also fond of the genteel remove of its art scene: “It’s really pretty bohemian, and I’m just one more local artist, which I like. I’m the one who doesn’t participate in the open studios each year.” Since moving here three years ago, Bronstein has transformed his slender 1670s house from a beige-dominated holiday cottage to a concoction of dark-panelled walls, elaborate mantelpieces, flush-folding shutters (which he paints over and over to mimic the passage of time) and cupboards pieced together from Georgian remnants. I’m in town to see his progress on two solo shows at Nottingham Contemporary and Chatsworth House, open from July, that explore the latter’s history and collections as part of “The Grand Tour” – a tourism project across Derbyshire and Nottinghamshire harking back to their cultural and economic wealth in the 18th century. The 37-year-old artist was an obvious choice for Nottingham’s director, Alex Farquharson, who coincidentally lives a few doors down the road in Deal. Bronstein’s practice has often explored the era’s proclivity for display, whether in building typologies or tableware, enjoying the obvious parallels with the superficial layering prevalent in the cheap architecture of postmodernism. Nottingham is hosting a loan show chosen by Bronstein from Chatsworth’s rich collections – including works by Frans Hals and Rembrandt, Delft vases, silverware and French and English display furniture – to highlight a period at the end of the 17th century when its interiors were remodelled and major purchases made: “The bulk of the house was rebuilt as a walk-around. And its collections represented a kind of grabbing at the world, a nouveau-riche excitement – the upper classes were captivated by the stuff going on in Europe at the time. I’m interested in the visual representation of power – Chatsworth shows how ornament and objects are employed to give a sense of distance and importance.”

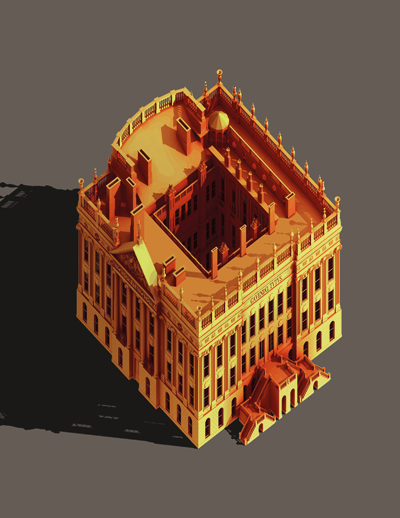

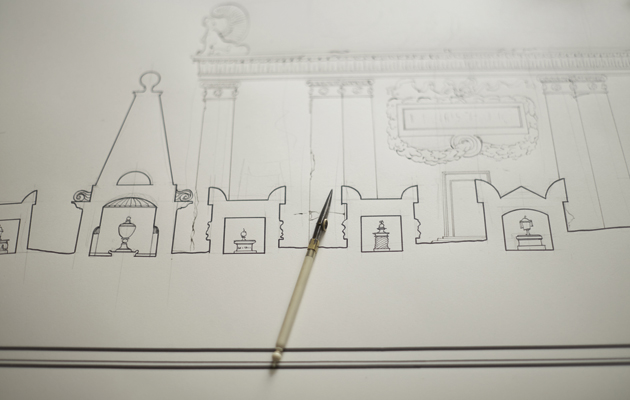

The 3D model of Chatsworth for the exhibition at Nottingham Contemporary The Nottingham display is to culminate with a huge drawing by Bronstein representing Rome’s Via Appia in a state of semi-dereliction in the seventh century, spread across 16 rolls of paper, each two meters long. He’s currently working on a cross-section of a huge vaulted mausoleum; rolled up nearby is a version of Etienne-Louis Boullée’s Cenotaph for Newton. Reference books on 17th-century decoration are scattered artfully around his desk, but he admits, “I tend to just go for it. Hopefully it should end up like a French Academy piece – a lot more cack-handed but sharper and more colourful. Intricacies of form aren’t that important – more important is horizontality, interspersed with a few incidents. The result should be a kind of Ozymandias landscape with fragments of power and authority in the sand, all displayed alongside ghostly fragments borrowed from Chatsworth – Canova’s casts of hands, a couple of column fragments, a huge marble foot.” Bronstein and his assistant are also embarking on a painful SketchUp learning curve to create a rotatable 3D model of Chatsworth. Things are still in progress when I visit, with heads being scratched as to the practicality of statuary on the cornice: “We’re going crazy on mind-numbing details, and it’s far from accurate, but it communicates a certain kind of study of the building. It’ll be cleaned up as a huge motif to be repeated and rotated to make wallpapers for Nottingham.” It’s a trick he recently used in two dimensions for shows at Turin and Houston: “It comes from a desire to obliterate and rework the context entirely – in visual terms at least.”

Pablo Bronstein and the Treasures of Chatsworth installation shot In contrast, Chatsworth is hosting a straightforward retrospective of Bronstein’s drawings. He toyed with ideas of a hard-edged performative work, but felt engagement was more important: “The people who turn up at Chatsworth are very different from the contemporary art world, and I genuinely like that spread. I’m not interested in the intricate games of contemporary art, per se, and think my work could have quite a large appeal, even a double audience. They will enjoy the abstraction, and will get into the ruins, the nitty gritty, the fantasy and fakery of it. The rest is fun for the art crowd, but that’s not why I make the work.” When we meet, Bronstein is undergoing a fit of indecision, debating whether to go down a colour or black-and-white route for his Via Appia drawings. The result is a rehang of his picture collection: on the floor beside me is a 17th-century Dutch painting of a church interior that, to his obvious satisfaction, once belonged to the architect Albert Richardson (1880–1964), famous for sporting Georgian clothes. Browsing auctions for such decorative treats is a source of both procrastination and pleasure: “The house is a mess and a money pit, but it’s a joy having an endless sprawl and not having to limit yourself on what you buy.” As we choose from three gaudy replica wallpapers for the spare bedroom (“My parents are going to hate staying here now”), he admits that there is “a touch of the natural contrarian” in both his decor and his artistic practice: “If the rest of the art world were in houses like this I’d be in whitewashed industrial buildings. But at the moment I’m one short step away from heavy curtains and swags.” Pablo Bronstein’s exhibitions at Chatsworth House and Nottingham Contamporary run until 20 September |

Words John Jervis

Portrait Julian Anderson

Images: Courtesy of the artist; Andy Keate |

|

|

||

|

Work in progress on the Via Appia drawings and, with Skyla Bridges |

||