The clean lines of mid-century modernism and its successors are what we have come to associate with Nordic design. But there is another, more colourful, story that is less often told

Photography by Bukowskis featuring Fredrik Paulsen’s demountable chairs

Photography by Bukowskis featuring Fredrik Paulsen’s demountable chairs

Words by Riya Patel

The early 21st century was defined by the idea that good design must be minimalist. From 1998 it took just nine years for Apple to go from making bulky bubblegum-coloured iMacs to revealing the sleek iPhone – driving a global obsession for the stuff of our lives to be slimmer, smaller and therefore better (at least according to its ruthless marketing).

The reductivism at work in technology and product design would come to influence mainstream tastes in furniture too. The slim legs, sharp angles and clean lines of Nordic mid-century design have made it the dominant force in the home interiors market over the last decades. Associations with simplicity and functionality have made design from this region a seemingly unstoppable global force.

Now, almost a quarter of the way into the century, it seems we’re feeling about for a new expression. Times are uncertain, and while some tread safe ground in clinging to styles from the past, a new set of Nordic designers is looking to put its own spin on the region’s respected design heritage with a more personal approach.

Photography featuring KevinHviid’s BobBench

Photography featuring KevinHviid’s BobBench

The brand of Scandinavian modernism, exported so successfully around the world since the postwar era, is seen as calm, tasteful and dependable. Craft, quality and reduction to essence are values upheld over clashing patterns, colours and shapes that break the mould. Natural light is prized more than anything in the long dark northern winters, meaning ornamentation and clutter are often avoided.

Where Nordic design has historically flirted with maximalism, a once-in-a-generation risk-taker led the way. It took an Austrian, the visionary Josef Frank, to introduce vibrant botanical prints to Swedish interior design firm Svenskt Tenn that railed against puritanical principles and the universality of modernism.

Fleeing growing antisemitism in his home country in the 1930s, he saw standardisation and uniformity as threats, beyond interiors to people themselves. In the wake of his influential designs, others in the region took maximalist risks too: Oiva Toikka’s quirky glass accessories for Finnish brand Iittala in the 1950s, Maija Isola’s unmistakable Unikko (Poppy) print for Finnish design house Marimekko from 1964, and the rebellious prints of Swedish 10-Gruppen in the 1970s.

Thanks to this lineage, textile and accessory designers in the Nordics seem to have been given more licence to be experimental compared to their furniture-making peers. ‘We’re always outsiders,’ says Danish designer Kristine Mandsberg. ‘We’re not architects or industrial designers. We’re always the ones who apply stuff to other people’s work. For us it’s normal to work with colour, ornament and pattern. I can be more liberal with my work because this is what textile designers do.’

Photography Daniel Schriver featuring Kristine Mandsberg’s Woven Foam

Photography Daniel Schriver featuring Kristine Mandsberg’s Woven Foam

Nevertheless, when Mandsberg went to study at London’s Royal College of Art, surrounded by people ‘from all over the world’, she noticed she had subconsciously absorbed the minimalist aesthetic influence of her home country. ‘I was amazed that where I came from was so obvious in my work,’ she says.

Her experience in London led her to a bolder use of colour, seen in interior textile sculptures like Fringe Mountain (2020), made from shaggy strips of nylon jersey in candy pink and yellow, or Woven Foam (2019), experimenting with vivid purples, oranges and pink. ‘I found out that I could be a maximalist with colour. My way of working with it is quite loud, and that’s not what you’d normally see here in Denmark.’

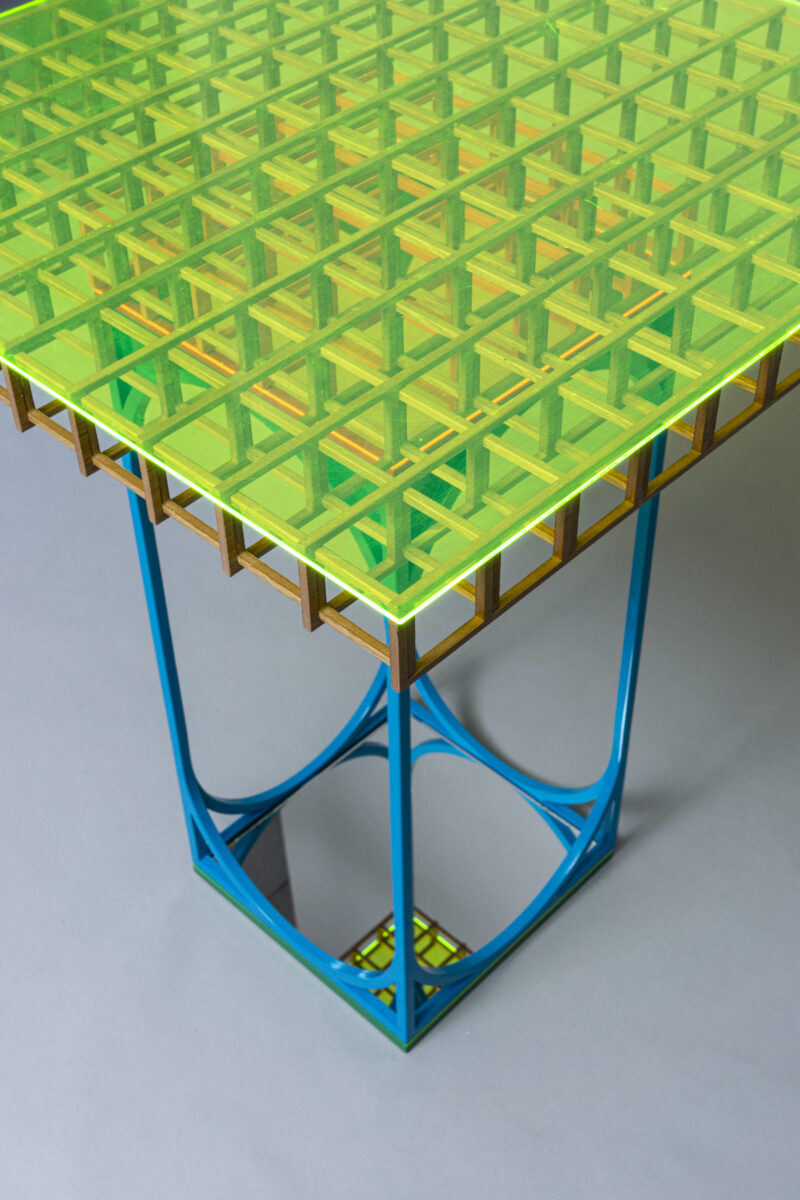

Danish architect and furniture designer Kevin Hviid is also no stranger to vibrant hues. His Copenhagen-based studio’s brightly coloured designs such as Oli Table (2020) and BOB Bench (2016) play on optical illusions and the radical postmodern designs of Memphis. These statement pieces employ a palette of mirror, tubular steel, brass and fluorescent plexiglass – as well as the more usual wood – to depart from the maxim that form should follow function, and instead explore the graphic qualities of furniture.

While Hviid’s style might turn heads among some traditionalists, he has gained national respect for taking Danish craft in a new direction. In 2018 the throne-like Billy Bench was selected for Mindcraft – the Danish Arts Association’s annual showcase at Milan Furniture Fair. Iris, a technicolour swing seat made in collaboration with fashion house Ganni, was among the experimental designs of the Danish Cabinetmakers’ Autumn Exhibition in 2017.

Photography featuring KevinHviid’s Oli Table

Photography featuring KevinHviid’s Oli Table

Talk of ornament and style in architecture and design is a surefire way to spark a debate. Our aesthetic preferences are subjective, highly personal and also likely to change depending on our age, upbringing and cultural influences. Scandinavia’s brand of minimalism has successfully prevailed for so long because it is unlikely to offend. Danish glassblower and designer Alexander Kirkeby knows his work is divisive.

‘If you want a drinking glass to function and not do anything more than that, then the glasses I make are not for you,’ he says. ‘Mine are tactile. They have distorted shapes, so every time you drink from them you have a different experience. That forces you to really think about the object.’ Kirkeby’s inspirations go back to the Renaissance and Baroque periods, with their complex ornamental objects – he loves the level of craft involved and the sense of discovering the minutiae of their details over time.

Kirkeby’s process involves repeating the same ornamental element over and over until it becomes distorted. His side tables for Ukurant – a platform for experimental Danish design started in 2020 – are based on some Renaissance-era silver tables he’d taken an interest in. ‘I could see [the design of the tables] translate into a technical way of blowing glass with layers of decoration. Layers that are built up slowly and almost melt out.’

The Royal Danish Academy of Art graduate is noticing a more expressive approach to design among his generation, many of whom also exhibited with Ukurant. ‘I think it’s a reaction to decades filled with very strict and geometrical design, especially from Denmark as that’s how the world sees us. But not a reaction against it, like it should be destroyed. Coming from a minimalist approach to design can give us something very unique. There is a lot of aesthetic potential in the combination of the two.’

Photography by Sofie Flinth Bredholt featuring Alexander Kirkeby’s glass work

Photography by Sofie Flinth Bredholt featuring Alexander Kirkeby’s glass work

The Royal Danish Academy of Art graduate is noticing a more expressive approach to design among his generation, many of whom also exhibited with Ukurant. ‘I think it’s a reaction to decades filled with very strict and geometrical design, especially from Denmark as that’s how the world sees us. But not a reaction against it, like it should be destroyed. Coming from a minimalist approach to design can give us something very unique. There is a lot of aesthetic potential in the combination of the two.’

Many designers and makers who take a maximalist approach have found a home in the design-art scene of independent galleries, rather than traditional manufacturing. Fredrik Paulsen’s highly individual style often has the Swedish designer labelled as an artist, but he is always quick to correct. ‘I always ask to be called a designer because we somehow need to expand the perception of [the role]. I love working with galleries and manufacturers, I don’t see them as polar opposites.’

While the scene for collectible design was growing strong in London around the mid-2000s, it didn’t exist in Scandinavia until much later. Paulsen started the group platform Örnsbergsauktionen in 2012 to have fun, bring people together and infuse Stockholm with the same energy as London’s independent design scene.

‘I moved into this huge studio out of town and wanted to activate it,’ he says. ‘So we did an auction. We had 1,500 people in a 70 sqm space – it was like a nightclub.’ Running for five years, the event became a fixture in Stockholm’s design scene and kickstarted a culture of pop-up shops and small galleries. These are driven by designers taking the initiative to create and show their own work, rather than wait for a collaboration with a manufacturer.

Photography by Louise Enhörning featuring Fredrik Paulsen’s Mjölkpall

Photography by Louise Enhörning featuring Fredrik Paulsen’s Mjölkpall

Paulsen’s original aesthetic of rainbow colours, paint splatters and raw industrial materials shows more reverence to the DIY punk scene than Swedish modernism. His first loves being skateboarding and clubbing, Paulsen says he never knew about design growing up, and came into it by chance. The outsider stance has helped make his name and introduce new paths for young designers.

From his studio he makes furniture on request, like his dyed and waxed pine Mjölkpall stools, as well as limited-edition work, such as with the Copenhagen-based gallery Etage Projects. Soon he will launch Joy, his own line of direct-to-consumer furniture that is flat-packed and customisable by mixing and matching elements.

Though Paulsen thinks it is important for designers to continue working with manufacturers for overall progress, he is frustrated by the failure of the furniture industry to keep up with the times. ‘How is it possible for designers to earn a living with a 4-5% royalty?’ he asks. ‘Brands talk about sustainability but a designer would have to create stuff to sell in huge quantities to survive. And so designers need to propose things that appeal to everyone.’

Photography by 13 Desserts featuring Fredrik Paulsen’s Azur chair

Photography by 13 Desserts featuring Fredrik Paulsen’s Azur chair

The conservatising effects of the system may be one reason minimalism has been in vogue for so long. Paulsen thinks returning to a pre-industrial way of making furniture would be more advantageous for consumer choice, the environment and designers’ livelihoods. ‘If you make personal work that is not aimed at everyone, but a niche, you can sell it in the hundreds not the thousands,’ he says. ‘And you have a real relationship between product and consumer. You are less likely to change the furniture when it doesn’t suit.’

Could the environmental agenda be the thing that turns manufacturers from minimalist please-all designs to shorter, louder and more bespoke runs? Probably not. Although a more responsible attitude to production would be welcome, the world’s associations of Nordic design with craft, quality and timelessness will ensure it stays in high demand.

The classics will continue to endure as a shorthand to our collective sense of respect to it. Maximalism remains alive in the hands of a few outsiders. But with a flourishing independent design scene across the Nordics, those contrarians and risk-takers are growing in number. They may come to challenge our view of what design from this region could and should be.

This article was originally featured in ICON 207: Spring 2022. Read a digital version of the issue for free here

Get a curated collection of design and architecture news in your inbox by signing up to our ICON Weekly newsletter