|

|

||

|

An energetic new generation of South African designers is finding a global audience for the country’s local design scenes, from Cape Town’s Woodstock district to the bustle of Johannesburg Studio visits help you understand the voice of a city,” says Evan Snyderman, one half of R & Company, a New York-based design art gallery. Snyderman and his partner Zesty Meyers exhibited at Cape Town’s inaugural Guild Design Fair this February, and, since it was their first visit to South Africa, they made time to scope out local makers and studios. “There’s a palpable energy and a real drive for designers to express themselves here,” says Meyers. “It feels like South Africa is on the brink of having a moment.” If you have been there recently, you’ll agree. Design Indaba, now in its 19th year, has people queuing around the block to get in. The Cape Town Art Fair, now in its second year, showcased 34 leading South African galleries, including heavyweights Stevenson, Goodman and Everard Read. Artist Brett Murray, whose painting of President Zuma exposing his genitals (entitled The Spear) brought him fame and notoriety in 2012, was signing books. Throughout 2014, as Cape Town celebrates its status as World Design Capital, studios and workshops across the city are pulling out all the stops.

Corner chair and pedestal, Gregor Jenkin and William Kentridge

Migrant Migrate, Gregor Jenkin The city’s creative heartbeat is Woodstock. A decade ago, it was a no-go zone, occupied by insalubrious characters and run-down industrial buildings. Entrepreneurs, artists and ahead-of-the-curve thinkers moved in and have turned derelict plots into enviable studio spaces. Every Saturday, the buzzing Neighbourhoods market takes place at the Old Biscuit Mill, a 19th-century former biscuit factory. Andile Dyalvane and Zizipho Poswa run their gallery, Imiso Ceramics, here. “I’ve been based in Woodstock since 2006 and have seen the area change,” says Dyalvane. “Those who remain: the Rainbow Tavern next door with weatherworn, crutch-armed street roamers attracted to its blearing drunken outbursts; those who sell knick-knacks, smokes, factory-reject socks and dish cloths. And those who come and go: the branded delivery vehicles; the sightings of trendy, eclectic 20-somethings armed with lattes.”

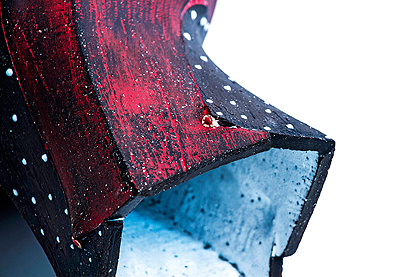

Studio Session (detail), Imiso Ceramics

Studio Session, Imiso Ceramics Dyalvane constantly draws inspiration from his city; last year his Docks table, produced in a limited edition of five for South Africa’s leading design art gallery, Southern Guild, was inspired by the view from his studio. “Docks started off representing the containers being loaded on and off the ships parked at the docks. I used to watch them every day.” For Imiso, his clay pots, decorated with markings inspired by ukuchaza (tribal scarification) are signature pieces, alongside Poswa’s Pinch bowls, which first got them noticed at Design Indaba in 2007. “Perspectives are broadening and marketing momentum for new works and proposed collaborations is becoming terribly exciting,” says Dyalvane. Three years ago Charles Haupt and Otto du Plessis moved their foundry, Bronze Age, into a 760sq m space nearby. With a staff of 30, it’s one of the largest foundries in the Cape region. Small bronze bowls and jacaranda skulls carved by its resident sculptor Friday Jibu, limited-edition design art pieces and figurative public artworks (horses, divers, Zulu warriors) are cast on site in wax and sand. “It definitely feels like the right place, right time,” says Haupt. “It’s really exciting to be a South African designer right now. There has been a massive growth in interest for design from my country over the last couple of years, both locally and internationally.”

Quaker chairs, Gregor Jenkin Twenty-six-year-old Laurie Wiid van Heerden was an assistant to sculptor Wim Botha at Bronze Age before striking out on his own in 2010. This summer, he is collaborating with DHK Architects to construct a temporary cork pavilion in Cape Town’s Company Gardens. It will be the first cork structure in South Africa and is a continuation of his experiments in the material dating back to 2012, which resulted in tableware, lighting and furniture. More recently, his 3m-long steel bench in a variety of finishes has resulted in high-octane, local collaborations with the likes of artist Lionel Smit and Ceramic Matters. “The South African design community is quite small and the opportunities are great, but we are still struggling in getting our work out there. I have only recently started doing well with regards to sales and exports. It takes time to build that awareness,” says van Heerden.

Num Num table, Bronze Age

Bronze bowl, Bronze Age Porky Hefer’s studio has been described as “the most beautiful office in the world”. It’s no exaggeration. A former farmhouse turned artist-in-residency in the upscale neighbourhood of Oranjezicht, which nestles between Table Mountain and Lion’s Head, it’s an idyllic spot that any designer would dream of. Prototypes are dotted around on a shady verandah, while Hefer’s Nest hangs from a tree in the lush garden. Since 2009, he has been perfecting its form, which was inspired by the intricate nests of Africa’s weaverbirds. Nest exists in hanging and standing versions in materials ranging from cane to recycled plastic packaging straps and hand-stitched rubber tyres. The most recent incarnation, entitled Bettina Esca, is a hanging version made with leather offcuts. With Southern Guild, it’s now on the international fair circuit, and Hefer is extending the Nest concept to the design of a house near Sossusvlei in Namibia that has four bedrooms, a sunken lounge and a cellar.

Skull Candy, Bronze Age For 16 years, Hefer, who sports a bushy beard and neon trainers, worked as an advertising creative at home and abroad. In 2007, he started his studio, Animal Farm, and set about embracing Africa and its indigenous skills and processes, rather than looking abroad. “Most of us here are designer-makers and marketers and packers and distributors. We make all our designs for our own brands rather than for big manufacturing companies. It’s almost as if Africa missed the big industrial mass-manufacture phase that the northern hemisphere is in. I think we are almost lucky, as it seems the rest of the world is coming back to handmade and crafted.” For furniture maker Gregor Jenkin, collaboration with South African artist William Kentridge in 2007 fast-tracked him into design art circles. Kentridge was also the first patron to buy one of Jenkin’s tables. He now owns three. “I first met Gregor seven years ago at his studio in Johannesburg,” says Kentridge. “He’s the South African designer I’m most interested in. I like his particular clean lines.” Together, the pair created eight tables to accommodate the art film, What Will Come (Has Already Come). Since then, the collaboration has grown to include chairs and a desk which have jagged laser-cut legs formed from paper tear-outs, sent by Kentridge to Jenkin.

Audrey Esca nest, Porky Hefer

Stel, Porky Hefer Personal, rather than business, reasons brought Jenkin to Cape Town three years ago. Dotted around his airy Woodstock studio are functional tables and chairs and conceptual works such as Migrant Migrate – a series of 24 folded and bent metal tables, designed to stand “like a herd of wildebeest”. Cape Town has more designers than any other South African city. Who could fail to enjoy its outstanding natural beauty, sense of space and creative energy? In terms of manufacturing, business and clients, though, Johannesburg leads the way.

LALA drinks cabinet, Pipe planters and Slide table, Dokter and Misses “Jo’burg is fast and rough and full of driven people,” says Adriaan Hugo, one half of Dokter and Misses, which was co-founded with his wife Katy Taplin in 2007. Today, they run Co-op, a studio and showroom in the creative hub of Braamfontein. Their Kassena cabinet, which features bright patterns inspired by the decorated houses of the Kassena people of Ghana, brought them international acclaim last year. Further experiments in pattern and form include the LALA Shwantla cabinet, launched at the Guild Design Fair, and the Veld couch, a two-seater sofa encased in a trellis- like steel cage. Taplin, a graphic designer, takes inspiration from wholly African motifs: “the houses of the Basotho and Ndebele people, burglar bars and trellis work”. The duo is developing a range of furniture with Gone Rural in Swaziland, which will be the transformation of its graphic style into weaving techniques. The limited-edition, artisanal approach appears to be defining South African contemporary design.

Sweat lamp, Dokter and Misses

Veld couch, Dokter and Misses Through Southern Guild, all of these designers travel to major fairs and display the unique qualities of South African design to the world. The gallery’s co-founder, Trevyn McGowan says: “Craft is very old in Africa, but design is very young. Part of the global appeal of contemporary South African and African design is that it is unfettered, imaginative and energetic. The work has an underlying passion, a beat and a pulse. Taking South African design to the world has given us an opportunity to see who we are in this international forum.” Aaron Kohn, director of the Museum of African Design, which opened last October in Johannesburg’s Maboneng Precinct, says: “Good design doesn’t only have to have a £10,000 price tag, and many designers are creating reasonably priced design, too. The challenge is that South Africans still consume imported, rather than local, products. But it is moving faster than it was. There are more design graduates and more manufacturing outlets, so it’s easier to get things made.”

a-001L (heartbeat), Dokter and Misses The spotlight may be shining on Cape Town this year, but to date, it has not been seen as a global design hub. “I think the world sees South African design as an uncharted landscape, something that is very difficult to put into a specific category, as our democratic country is so young and there are so many cultural differences,” says van Heerden. There are many other obstacles to overcome. he nation’s most pressing concern is to tackle the glaring imbalance between extreme privilege and extreme deprivation. Hefer says: “We have fantastic, incredibly talented designers in South Africa, we just need to improve the business side of it. We need to turn it into a sustainable industry that supports its designers so they can grow, inspire and employ. We need the government to help with incentives to get the work to the international markets at a competitive price and we need the brokers to mutually benefit from South African design rather than take advantage of it. Perhaps it’s time for the big design houses of the north to look to Africa for talent rather than just inspiration.” |

Words Emma O’Kelly |

|

|

||

|

LALA Schwantla cabinet, Dokter and Misses |

||