|

|

||

|

A new generation of Polish designers is rejecting the cool minimalism that characterised the post-1989 years and showing a renewed interest in vernacular and traditional crafts. Their textiles and ceramics are defined by colour, decoration and an ability to “think through patterns” Contrary to the popular slogan uttered by Adolf Loos some 100 years ago, ornament is no longer a crime. For years, the apartments of young Polish creatives were dominated by sterile minimalism and a cool, post-industrial aesthetic – a reaction to the kitsch interiors their parents installed during the nascent capitalism of the late 1980s, and to the redevelopment of former industrial buildings in major Polish cities. Now, however, young Poles are once again opening up to more colourful and energetic furnishings. The term “applied arts” evokes aspirations formed during the 1920s and 30s of “applying arts to industry”, which still shape our contemporary notions of product and industrial design to a significant degree. Today, this term may seem awkward and obsolete, but in Poland it is actually quite apt when describing current design tendencies: pattern and illustrations are increasingly prevalent, with designers eager to demonstrate their ability to “think through patterns” – an impulse that extends to those working in both two and three dimensions. The profusion of ornament in contemporary Polish design stems in part from a revival of interest in traditional craft and vernacular cultures. This has been intensified by several exhibitions of modern and postmodern design, such as 2010’s We Want to Be Modern at Warsaw’s National Museum, which presented prototypes made at the Institute of Industrial Design in the 1950s and 60s under the guidance of its legendary founder Wanda Telakowska – she maintained the relationship created before the war between designers and folk craftsmen, and donated the institute’s collection of ceramics, furniture and printed and woven textiles to the museum in 1978.

Butterfly vase, from the Drawn Objects series by Maria Jeglinska Last year’s retrospective of Italian designer Alessandro Mendini in Wroclaw encouraged a further reappraisal of ornament’s role in contemporary design, and coincided with Mendini receiving an honorary degree at Wroclaw University. Thus, metaphorically, postmodernism has reached the banks of both the Odra and Vistula rivers, reinforcing something that could already be felt in the air. Since Poland joined the European Union in 2004, the world has become increasingly accessible to Polish students – the Socrates-Erasmus exchange programme and the Bologna system have boosted mobility, allowing students to continue their education in Eindhoven, Lausanne or London. One of the first designers to profit from those expanded horizons was Tomek Rygalik, who attended both London’s Royal College of Art and New York’s Pratt Institute after graduating from Lodz Polytechnic. Having accepted a post at the Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw, he encouraged his students to follow in his footsteps. In this globalised and densely networked world, a clear definition of national identity within visual culture becomes almost impossible. Irrespective of location, culturally aware individuals tend to follow the same blogs and read the same magazines as their international peers, dealing with the same issues that affect precarious creative classes the world over.

Saucer by Fenek (Agata Klimkowska and Tosia Kilis) There can, however, still be brief moments of collective national consciousness, often enabled by the dissemination of ideas across the internet, just as that same network may cause such moments to dissipate amid the global stock of images and ideas. And such a moment is perhaps visible in the current attitude towards pattern-making in Poland. Oskar Zieta, based in Wroclaw, is one of the most innovative Polish product designers of his generation. Zieta gained a global recognition for inventing the FiDU manufacturing technology and consequently launching the Plopp seating family with Danish company Hay. He is currently developing several collections for Manufaktura Boleslawiec pottery – the company is renowned for the dark blue stoneware that is exported all around the world as a typical Polish folk gift. Zieta has experimented with adding fresh designs to the pottery’s traditional catalogue, with flocks of birds, wood grain and geometrical and linear motifs, all in black and white only – a contrast with the firm’s traditional polka-dot patterns. He has also attempted to enhance manufacturing and decorating processes at a company that still makes all of its products by hand, introducing new technologies while still preserving the final artisanal effect. This example is part of a wider trend in the way established factories, which have been selling the same sorts of goods for decades, are starting to perceive and appreciate design and designers. For several years the Kristoff porcelain factory in Walbrzych has invited fêted designers and illustrators – including product designer Maria Jeglinska, fashion designer Ania Kuczynska and graphic designer Karol Sliwka – to decorate their porcelain, receiving critical and public acclaim. Warsaw-based graphic designer Magdalena Pilka Pilaczynska has produced some of the most celebrated patterns, for instance the Flamingo and Moustache designs – two breakfast sets with retro-looking motifs in light pink, blue and contrasting black, featuring light-hearted inscriptions in French and English.

One of the patterns developed by Oskar Zieta for Manufaktura Boleslawiec

Touch of Blue collection by Marek Cecula and Daga Rogers for Cmielow Following in Kristoff’s footstep is another porcelain factory rooted in Polish design history: Cmielow, best known for the organic forms it produced during the 1950s and 60s. After Marek Cecula – a ceramist based in Poland and New York – initiated Cmielow Design Studio in 2013, the company developed products targeted at younger customers. The Touch of Blue collection, designed by Cecula and his colleague Daga Rogers, is a useful example, representing a contemporary evolution of the company’s classic cobalt-coloured porcelain sets. Traditional cobalt decoration seems to appeal to younger generations too, given a new twist by the likes of Malwina Konopacka and Magdalena Estera Lapinska, two independent illustrators who have been experimenting with ceramics. Konopacka’s recent solo exhibition at the Pies Czy Suka concept store in Warsaw, titled OKO (The Eye), revealed her passion for post-war aesthetics. Ivory ceramic vases with recesses evoking eye sockets were painted with primary colours – red, yellow, blue and black in various constructivist and organic shapes – or meticulously decorated with platinum and gold. In other cases, vases were embellished with more familiar cobalt patterns created using a wide, soft brush, echoing the sort of hand-painted earthenware popular in middle-class households during the Communist period. A similar impetus could be observed in Fenek, the studio established by Agata Klimkowska and Tosia Kilis last year while still studying at the School of Form in Poznan. Their vessels – bowls, plates, cups, but mostly flowerpots – are currently manufactured using the school’s facilities. From a limited colour palette (predominantly cobalt, again), they create patterns that combine the soft, organic styles of the 1950s and 60s with crisp, Memphis-like zig-zags and New Age-esque marbling.

Hand-painted OKO vase by Malwina Konopacka

Shawl by Kasia Skorzynska for Kaaskas This preference for combining illustration with three-dimensional objects such as ceramics or textiles is a leading trend in contemporary decorative arts in Poland. For some practitioners, such as the aforementioned Maria Jeglinska – who explicitly describes her process as “thinking by drawing” – this process has developed its own set of methodologies. Many of Jeglinska’s products, such as her Drawn Objects series (hand-painted, abstract wooden vases), the Goodie stool, manufactured by Cinna, or the recent Little Black outdoor chairs produced by Vox, all originate from drawings and collages that have been made with no prior intention. Poland still lacks an established community of pattern designers – there are as yet no specialist studios in the mould of London’s Patternity or Pattern Foundry. This situation is perplexing when you consider the bold history of Polish printed textile design from the 1950s and 60s, a period during which designers explored traditional folk methods such as stamping and cut-outs. When viewing examples from this era in the warehouses of the National Museum in Warsaw, one is struck by how contemporary they look, even now. However, this legacy may finally be about to escape the museum’s storage units, largely thanks to

Grids textile by Izabela Sroka and Julia Cybis of studio Falbanka Olka and Gosia Osadzinska established their company Paperworks to produce one product: top-quality decorative wrapping papers. These papers are thicker and thus more durable than those commonly available, enabling them to be reused. The patterns, mostly designed by illustrator and graphic designer Olka, range from simple shapes, such as diamonds, fleur-de-lis or anchors, to exotic fauna and flora inspired by John James Audubon’s Birds of America. Paperworks also commissions work by the best Polish illustrators, among them Ola Niepsuj and Katarzyna Bogucka – the space beneath Christmas trees may soon be one of the best places to analyse the strengths of Polish graphic design. In December 2013, Magdalena Heliasz –author of a respected blog about Polish printed matter, Print Control – came up with yet another promotional tool: a series of pattern books simply named WZORY / PATTERNS. The standout contributions in the first issue were works by Jakub Jezierski, with his cacophony of vector shapes, transparencies and gradients. The following issue, due soon, features works by Malgorzata Gurowska, who explores her idealistic, post-humanist approach to design through a set of patterns inspired by cages, mesh, chicken wires and other sorts of barriers. This interest in “undesigned” objects is linked to another important tendency in Polish design – an interest in the vernacular. The trend has taken root in cities such as Wroclaw and Lodz. A case in point is the “type spotting” (or typopolo) movement, which documents the amateur typography and design of commercial and shop signage – again, critiquing remnants of the early years of Polish capitalism has become something of a national pastime. This interest in the aesthetic value of everyday surroundings has resulted in a new design language that combines the abstractly poetic with the socially analytical, as seen in the Grids textiles by Falbanka studio that are being produced in Lodz, the former capital of the Polish textile industry. Similarly, the Polish Bars notebooks by Magdalena Piwowar, published by Centrum Architektury Foundation, draw on sources such as rural fencing, concrete paving blocks, window bars and balcony designs found in Poznan, Tarnow and Sadlowo – you’d struggle to get more site-specific than that!

Warsaw Districts: Wilanow poster by Edgar Bak Another cult graphic designer of the current generation, Edgar Bak, likes things to be less literal. The window bars he found in Wroclaw during the Out of Sth festival in 2012 were subsequently employed as modular, abstract grids, which could be manipulated in manifold ways. Presented in bold black and white, they became purely decorative, without any direct referent. The same could be said about Bak’s posters representing individual districts of Warsaw, which reduce each locale to the starkest possible set of signifiers. With his ability to distil order from chaos, Bak is obsessed with visual arrangement, believing that through his work he contributes to the creation of a reality “that we would all want to live in: international, logical and adequate”. Bak freely admits that his passion for the international modern style – a mainstream visual language, characterised by accessible typography, icons and pictograms – is used as a tool to address the deficit of order in Polish reality.

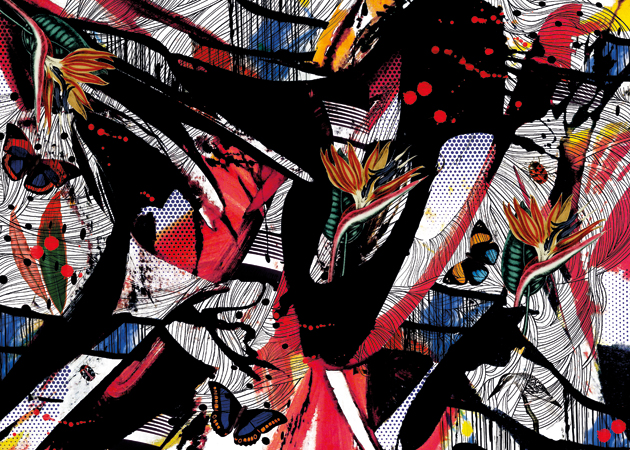

Above and below: Patterns for the Reebok Ventilator by Olka Osadzinska Perhaps, given the increasing homogeneity of global design, it makes sense to conclude with the most cosmopolitan of current tendencies in pattern-making, as popular in Warsaw as in Washington, DC – the post-internet aesthetics of glitch, collage and pastiche. This is most clearly visible in patterns designed specially in the context of fashion. Kasia Skorzynska, a graduate of the Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw and co-founder of clothing brand Kaaskas, makes dresses and shawls from fabrics that she designs herself. These collage-based textiles communicate the diversity of her points of reference. Constructivism, the Bauhaus and classicism collide with the hazy universality of floral prints and ambiguously ethnic motifs. Similarly, Paris-based Filip Nocko creates kaleidoscopic shawls under the name Filip von Polen that feature patterns created with multiplied photographs of typically Polish (or north-eastern European) animals and plants such as roosters, lynxes, foxes, brown bears, blueberries, raspberries or rowans – geographically locatable images that, once subjected to the visual rhetoric of the internet age, repeated, imbricated and decontextualised, are drained of meaning. Even though there may not be a new “Polish design school” in evidence – if such a concept even has meaning – we should at least acknowledge that there are creative individuals from Poland currently making their way through the global design scene, both at home and abroad. The renaissance of interest in the decorative arts is one encouraging indication of this new vitality, but it is only a first step. There are many more to take before we can truly claim that Poland is a well-designed country. This article first appeared in Icon 144: Poland. Click here to read more |

Words Klara Czerniewska

Above: Hand-decorated porcelain fox by Magdalena Estera Lapinska

Images: Turczynska for Culture, Bill Waltzer, Jan Kriwol |

|

|

||

|

|

||