|

|

||

|

The Shanghai-based duo reflect on why so many Chinese designers succumb to greed and explain why they’ve put the seven deadly sins in a Cabinet of Curiosities As they embark on their second decade in practice, Rossana Hu and Lyndon Neri have resolved to become more critical and provocative. We met the founders of Shanghai-based architecture and design firm Neri & Hu at Spazio Rossana Orlandi in Milan, where they were showing the Cabinet of Curiosity: a cupboard containing items representing the seven sins. The collection included a mirror, a dagger, an abacus, a sake set, tableware, a candle holder and scales. ICON: Lyndon, in 2010 you said architecture in China was “lost”. Do you still believe that? LYNDON NERI: The problem in China is that developers are greedy. The most talented designers tend to design phones and cars, because that’s where the money is. It’s a dangerous phenomenon – China can’t continue this route of trying to be bigger and faster than America. This approach, if not stopped, will have colossal effects. ROSSANA HU: I believe architects all over the world are lost. Traditional modes of production are no longer as valid and technology can replace architects in many ways. The way we experience space is also different, so the role of the architect needs to be questioned. Architects should take on new value in how they innovate in producing architecture.

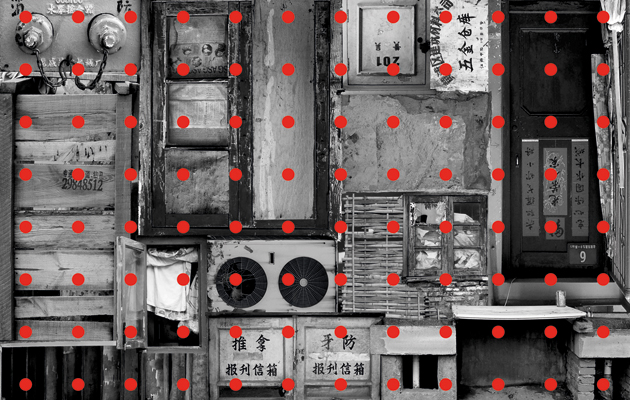

Top Neri & Hu’s wooden Cabinet of Curiosity for Stellarworks ICON: In the past you’ve expressed an interest in “local flavours”. How do you maintain this as your practice becomes increasingly international? LN: It’s definitely a challenge, because we became known for projects in Shanghai, such as Rethinking the Split House. But, although some of the aesthetic sensibilities of these may be Chinese, they deal with global issues such as sustainability, old and new, public and private. ICON: How do your product designs relate to your architectural work? LN: A lot of our products start out as a need in one of our architecture projects – they are part of a story within a project we’re working on. RH: We like to see the different scales we work on as a breath of freshness. If you’re working on the same thing for a long time, you lose perspective. During a day at work, sometimes we’re talking about an entire city and at other times we’re developing a pen, graphics or a chair. ICON: You’ve launched several products this year, for international names such as Lema and Moooi. How do you address the needs of each brand while maintaining your own style? RH: We study what each brand means and draw out its essence, then we try to see how it matches our personality. It’s the marriage of these two things that brings about something new. For example, for our printed carpet for Moooi we took photos of Shanghai mailboxes and streetsigns and superimposed vibrant graphics on top. The red polka dot, for example, is Moooi – fun, modern, loud – but behind it is us: Shanghai.

The confessions of visitors in sealed envelopes were contained in the cabinet ICON: Rossana, you recently challenged the idea of design always having to make you feel good, saying that it could instead be uncomfortable or unsettling. Could you expand on this? RH: It’s about defining what “good” is. Such terms no longer carry the value they used to, so we need to challenge their use. I like to talk about design as making a statement. What is the designer’s intention? What is your problem and how do you resolve it? For us, critiquing design is no longer just based on aesthetics – our culture is much more complex. LN: The typology of a home, office or museum is so fixed that even designers don’t think twice. At our Das Haus installation in Cologne earlier this year, we challenged the premise of what a home is and people felt uncomfortable – they would say, “that’s not really a dining room, it’s extremely tight and tall”. But why not? [Through this process] we start asking ourselves what we really need. In China, people want bigger houses and a long driveway, but you’re not even using that land – it’s an insane and dangerous tradition. ICON: Tell me about your Cabinet of Curiosity installation. RH: A “cabinet of curiosity” was how people used to display objects in the 18th century – items from their travels, things they were obsessed with. Today, people are most curious about others’ secrets – those inner thoughts you can’t reveal to anybody. The objects in the cabinet each relate to one of seven deadly sins – there are two pieces made in Japanese Arita ceramics, items designed by us, as well as found objects. ICON: You’ve been practicing for ten years. What does the next decade hold? RH: Definitely not bigger projects, but ones that point to how to resolve some of the problems in our cities, homes, products. LN: It’s time for us to be really critical. We’re starting to question programmes and business models – how do you work with developers, with internet companies, the sharing community? Perhaps we won’t design objects any more – perhaps we’ll design infrastructures. This article first appeared in Icon 147: Sins. Lyndon Neri will be speaking on 26 September 2015 at 100% Design during London Design Festival |

Words Debika Ray

Above: For Moooi’s photorealistic series of carpets, the designers superimposed vibrant graphics onto photos from Shanghai’s streets |

|

|

||

|

Gluttony was represented by a tableware set in Japanese Arita porcelain |

||