Bye Bye Kipling 1986, single channel video featuring live satellite broadcast. Via Electronic Arts Intermix (EAI), New York, and the estate of Nam June Paik

Bye Bye Kipling 1986, single channel video featuring live satellite broadcast. Via Electronic Arts Intermix (EAI), New York, and the estate of Nam June Paik

Nam June Paik began his career by destroying pianos with John Cage before becoming a pioneer of video art. Joe Lloyd explores Paik’s often absurd, but always technologically inquisitive work

All works copyright the estate of Nam June Paik

Some of the most succinct art emerges from happenstance. In 1974, the Korean artist Nam June Paik, looking to fill a gap in a soon-to-open exhibition at New York’s Galeria Bonino, brought in an 18th-century statue of Buddha he had purchased from an antique shop. Hours before the show’s opening, he plonked it down across from a white, plastic, orb-shaped TV. He then placed a camera behind the television, which fed a live recording of the sculpture into the monitor. The Buddha thus sat meditating before his own filmic image. As much as he strove to reach transcendence, he was tethered to the present by his own recorded form.

Self Portrait 2005. Image by Katherine du Tiel

Self Portrait 2005. Image by Katherine du Tiel

This work, prosaically named TV Buddha, became recurrent throughout Paik’s career; at one event in Cologne, Paik even sat in a meditative pose in front of a screen himself. This autumn, the original piece will form part of a retrospective of Paik’s work at Tate Modern. Although ostensibly simple, TV Buddha’s dialogic layout encapsulates the tensions – between technology and humanity, the earthly and the spiritual, East and West – that animated the artist’s entire career. One of the first artists to use video, Paik has numerous lessons to impart to the present day, when technology has intertwined itself with our lives more than ever before.

Read today, Paik’s views are remarkably prescient. ‘Skin has become inadequate in interfacing with reality,’ he wrote. ‘Technology has become the body’s new membrane of existence.’ In 1974, Paik coined the phrase ‘electronic superhighway’ to describe a conduit through which information and shared values could cross cultures. Four years earlier, he had come up with the ‘video common market’, proposing a free sharing of art that seems to anticipate YouTube. Such ideas were undoubtedly forward-looking but also stemmed from the historical moment into which Paik was born, and the creative milieus to which he belonged.

Prepared Piano 1962-63. Arter, Istanbul

Prepared Piano 1962-63. Arter, Istanbul

The genesis of many of his ideas lay in music. Paik was born in 1932 in Seoul, during Korea’s brutal occupation by Japan. His father, a wealthy textile manufacturer, was later discovered to be a collaborator with the regime. Growing up enmeshed in the haute bourgeoisie, Paik was trained as a classical pianist. But he soon broke away from the conservative music of his childhood. When his family fled the country after the outbreak of the Korean War in 1950, he enrolled in an aesthetics course at the University of Tokyo, where he presented his thesis on the composer Arnold Schoenberg. At one early performance, he smashed up the family piano in a gesture of defiance against traditional music.

After graduating in 1956, Paik set off in search of the music of the avant-garde and moved to West Germany for further study. There he befriended John Cage, whose interest in Zen Buddhism kindled Paik’s interest in his own Buddhist background. Not shy from embracing the extreme, Paik repeatedly tried to outdo Cage. While the composer would prepare pianos with small objects to create percussive sounds, Paik would use barbed wire or glue down the keys. A performance in 1960 saw him stop playing Chopin and start assaulting the piano, before charging into the audience, mutilating Cage’s clothes with a comically large pair of scissors, and dumping a bottle of shampoo over his head. Two years later, with Zen for Head (1962), he dipped his own crown into a bucket of ink and tomato sauce and drew a slippery calligraphic line with it, in a messy burlesque of his East Asian identity.

Still from Good Morning Mr Orwell 1984. Via Electronic Arts Intermix (EAI), New York

Still from Good Morning Mr Orwell 1984. Via Electronic Arts Intermix (EAI), New York

That same year, Paik was invited into the experimental art community Fluxus by its maestro, George Maciunas. In 1963, he mounted his first exhibition, Exposition of Music – Electronic Television, at Galerie Parnass in Wuppertal. Paik filled the gallery, which was based in its owner’s luxurious villa, with absurdist pieces. One attendee, a then-unknown Joseph Beuys, wrecked yet another piano and earned Paik’s lifelong friendship. The hallway featured the head of a just-killed ox, while a mannequin head was suspended upside-down above the toilet, so that those sitting on it would touch it with their own face.

It was here that Paik began to deploy the technology that became his hallmark. Thirteen televisions were strewn around the villa. By placing them in a gallery, he transformed what were everyday consumer electronics into objects that encouraged scrutiny and contemplation. He also welcomed accident: one of the television sets had arrived defective so it only displayed a single line of electrons, compressing the material it broadcast into a thin, abstract column of light. Paik decided to keep this defective set in the exhibition, naming it Zen for TV (1963). It would become one of his most famous statements.

Charlotte Moorman, Paik’s collaborator, with TV Cello and TV Eyeglasses 1971. Photo from the Peter Wenzel Collection

Charlotte Moorman, Paik’s collaborator, with TV Cello and TV Eyeglasses 1971. Photo from the Peter Wenzel Collection

‘People were starting to have these technologically complex black boxes in their house, and they didn’t really know how it worked,’ says Valentina Ravaglia, assistant curator of the Tate Modern show. ‘And he wanted to demystify them and break them apart and play with them, so that they would be more familiar with technology rather than enthralled by it.’ As an avid reader of the early information theorist Marshall McLuhan, it was clear to Paik that mass media was becoming the dominant form of his age – and could be a tool for making a new form of artwork.

In 1964, partially motivated by the relative cheapness of technology, he moved to New York, where he remained for the rest of his life, though with numerous international forays. During one such jaunt to Japan, he collaborated with the engineer Shuya Abe on the Paik-Abe Video Synthesizer (1969), a device that allowed Paik to edit multiple video images in real time. From here on, he was able to employ televisions in increasingly complex and madcap ways. A partnership with the radical cellist Charlotte Moorman, which lasted until her death in 1991, resulted in works that stretched the capabilities of the medium ever further. In TV Bra for Living Sculpture (1969), Moorman wore two screens as a bra, with the images transformed by her playing; TV Cello (1971) saw her play a ‘cello’ made from three TVs, which showed images of herself and other cellists performing when played with her bow. Humanity and machine were brought closer together.

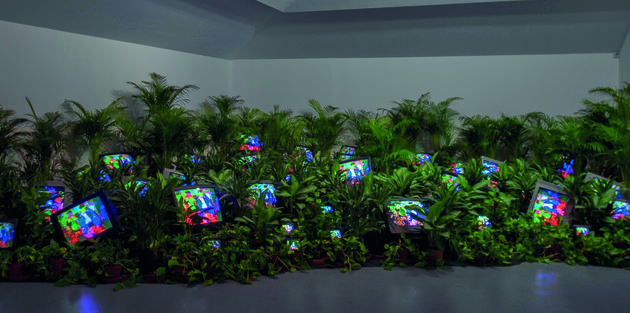

Installation view of TV Garden 1974-1977. Via Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen, Düsseldorf

Installation view of TV Garden 1974-1977. Via Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen, Düsseldorf

Television was not Paik’s only technological interest, though a mid-1960s research trip to the influential Bell Labs in New Jersey turned him off digital technology. ‘There were too many rules,’ explains Ravaglia. ‘Coding in the 1960s was a heavy-going affair. The type of processes that were needed for a computer program to run were too regimented for his taste.’ Robotics proved a better fit: in 1964 he and Abe worked together on Robot K456, a cluttered, ugly assemblage that originally featured breasts and a penis. Using radio signals, Paik could command it to fart out baked beans as it walked around, startling passers-by. ‘He wanted the image of the pathetic robot to allow people to understand the human side of technology,’ says Ravaglia. In 1982, Robot K456 even faced a human expiration, as Paik deliberately walked it into the path of a moving car outside the Whitney (thankfully it survived, though it is now too fragile to operate). He later made numerous robots from televisions, a series of delightfully ludicrous man-machines.

Three Eggs 1975-1982. Via Tate. Presented by the Hakuta Family to the Tate Americas Foundation

Three Eggs 1975-1982. Via Tate. Presented by the Hakuta Family to the Tate Americas Foundation

By drawing on the comic and the accidental in human existence, Paik hoped to democratise art and technology. Television provided this unifying medium. His 1973 film Global Groove juxtaposed avant-garde performance with appropriated TV commercials. This desire was perhaps taken to its furthest extreme by his turn to satellite broadcast. Beginning with Good Morning Mr Orwell — its name a rebuttal to the novelist’s dystopian predictions – aired on New Year’s Day 1984, he spliced live and pre-recorded footage of art and pop performances that were broadcast in various cities around world; an estimated 25 million people caught the programme. Later broadcasts saw his reach grow further, and, by melding avant-garde imagery with popular music, he had a hand in the rise of the music video.

Given today’s fears around surveillance, digital freedom, political manipulation and deep-fakes, Paik’s apparent optimism around media technology can seem a little confounding. He was conscious of its moral ambiguities in his own time. ‘He was very aware that the majority of technologies he used originated in military research,’ says Ravaglia. ‘But rather than point out the problems, he would be proactive and take these technologies from those who would use them for hegemonic ends and instead use them for peaceful purposes.’ Of all Paik’s lessons, perhaps this one – to take the potential tools of oppression and empower them for good – is the most resonant today. That; and that robots are hilarious.

The original version of this article appeared in Icon 197, the digital issue. Read more about digital waste here and how design is helping mitigate the problem of technological overload