Photograph courtesy NASA

Photograph courtesy NASA

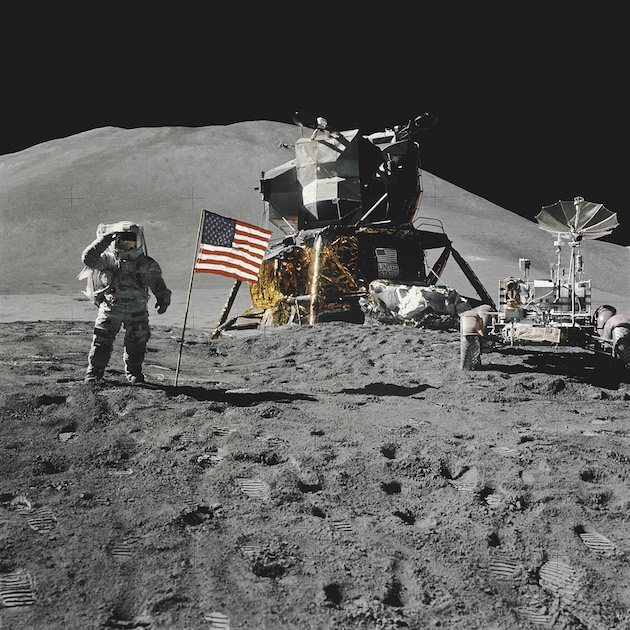

Neil Armstrong’s ‘giant leap’ came from the step of an awkward alien spacecraft that was at home on neither Earth nor moon, writes Matthew Ponsford

Looking down the barrel of his homemade telescope in 1609, Galileo was the first to confirm that the moon was not smooth, but pocked with craters and the scars of celestial collisions. The only exceptions, he thought, were the dark, shadowy areas he named ‘Maria’ because they looked like calm seas.

Neil Armstrong, hurtling sideways over the so-called Sea of Tranquillity 360 years later, could be forgiven for not dwelling on his second Galilean moment, seeing with his own eyes that those seas were not so placid after all. In 1969, at the culmination of the decade-long race to the moon, Armstrong’s view through the miniature windscreen in the Apollo Lunar Module – known as the Moon Lander – showed a landscape littered with gigantic boulders. With the sea’s hard grey face looming toward him, Armstrong had 20 seconds to decide whether to land or abort the mission, with the expectant world watching his every move.

BBC space reporter Reg Turnill listened on, terror-stricken, a quarter of a million miles away in Cape Canaveral, Florida, where he was thinking about the landing craft’s four strange, awkward legs. He pictured them catching atop a boulder and toppling it head over heels, condemning both Armstrong and his co-pilot, Buzz Aldrin, to become the first people to die in the coldness of outer space.

‘I never thought they could land that thing,’ Turnill told Rolling Stone writer Andrew Smith in his book Moondust: In Search of the Men Who Fell to Earth. As Aldrin shouted out alarm signals, warning that the ship’s computer was overloaded, Turnill knew for sure he would soon be reporting their deaths. Improbably, with 10 seconds of fuel to spare, Armstrong – unspeaking – touched the quadruped down between a boulder and crater and, he claims (even more implausibly), only then took a moment to think of something memorable to say as he disembarked.

When the first humans stepped out onto another world, they emerged from a 23ft gold-leaf insect on crooked aluminium stilts. The bug, as its engineers christened it, was incapable of flying on Earth, and had never been flown before Armstrong’s landing. A pure alien craft with walls barely thicker than a soda can, it was designed with a life expectancy of a little under two days in limbo. No Apollo lander would ever return to Earth. The Moon Lander was always intended to drift off into space, as the astronauts redocked with the command capsule that had orbited round the dark side of the moon with Michael Collins (the mission’s often forgotten man) and crawled back into a more robust capsule for atmospheric re-entry.

The Moon Lander was not supposed to exist. When the Apollo programme began, NASA first hoped, naturally enough, for a spacecraft that would go there and propel itself back. Instead, since calculations indicated that this would take too much fuel, in 1962 thoughts turned to a lightweight, disposable go-between. The design was based on a helicopter cockpit created by engineer Thomas J Kelly and his team at Grumman, who had made their name building propeller-driven fighter planes for the US in the Second World War. (Improbably, there were only 25 years between those Spitfire-like propeller planes and the moon landing.)

The result was probably the ugliest bit of early NASA space gear. From its earliest days, NASA, which celebrates its 60th anniversary on 1 October, has been a wellspring for era-spanning design inspiration, despite giving short shrift to aesthetics. Ralph Morse’s Life magazine images of the Armstrong family at home in 1960s Houston were one of two extreme poles of space-age style – the astronauts’ military dad aesthetics colliding with the proto-disco glamour of the reflective silver Gemini spacesuits. Later decades continued the hot streak, with the smooth NASA ‘worm’ logo, the Space Shuttle on its giant rust-coloured launcher rocket, and the stately International Space Station.

The Moon Lander, for all its importance, would never fit in. Moondust author Smith describes it as looking ‘as though it was assembled from toothpicks and egg cartons by a class of five-year-olds, then roughly covered in foil by their moms’. At half a century’s distance, the bug is stranger still each time you look at it. Angular and asymmetrical, it is difficult in images to even gauge its scale – for lack of any familiar surroundings from which to extrapolate height – except for when a suited astronaut walks in front of it.

Yet, in its inscrutability, it is the perfect space-age mind-puzzle to exercise the imaginations of wannabe astronauts (primary school me included). Despite its unwanted conception, the bug became the unlikely hero of the Apollo 13 mission – where it acted as a life-raft for three astronauts after the main craft failed – and for the foreseeable future, this oddball will remain the only vehicle to have taken humans to set foot on another world.