|

|

||

|

Part investor, part industry-navigator, Map Project Office helps crowdfunded ideas to become a reality. Could this be a model for other studios to follow, asks Will Wiles? First things first – where does the name come from? ‘We were looking for a short name that was very different to Barber & Osgerby,’ says Jon Marshall, design director of Map. ‘Clients were coming to us saying they wanted to use design as a tool to get somewhere, but they didn’t know the route,’ he continues, perhaps sensing that his first answer lacked a little mystique. ‘We think we have a process that allows clients to get to where they need to go, [a process] that’s strategic. That’s what I usually tell people.’ Given that, it’s very apt that one of Map’s most high-profile recent projects was a tool to get somewhere. Beeline is a navigation device for cyclists. GPS-enabled smartphone maps have, of course, revolutionised the way we find our way around cities, but they have their limitations when you’re on a bike. You need special kit for your handlebars, or you have to stop and fish the phone out of your pocket; they can distract attention from the road, and the information isn’t presented in the most digestible way. Beeline is a compass-like object that attaches to the handlebars with an attractive silicone strap. Once a destination is entered via an accompanying app, all it shows you is the distance, and a nice big directional arrow. You can choose your route yourself, and it will keep you going in roughly the right direction. So Beeline could be looked at as the perfect metaphor for the studio that created it. But it’s more than that. The way it came about is exemplary of a new business model for design studios – one that could set a new direction for many similar companies, and for the industry as a whole. Map is in the uncharted areas between design, manufacturing and entrepreneurship, and what it is finding there is fascinating. Barber & Osgerby, the industry-leading studio of British designers Ed Barber and Jay Osgerby, has spawned a couple of subsidiary brands. Universal Design Studio, for instance, is the company’s architecture arm. And Map, founded in 2012, is the consultancy arm – but that simple description hides some of the ways it has evolved. As Barber & Osgerby grew, it found it was taking on more work advising large technology clients, such as Sony and Google. These companies, with their own large, experienced design teams, were very different to clients such as Vitra, to whom the studio was more accustomed. ‘They were demanding a more collaborative approach,’ Marshall says, ‘and often demanding something more strategic that didn’t necessarily end in a product, but could be seeded into their in-house design team. Which is quite different from the very authored work that Ed and Jay do.’ Map was set up as a ‘white label’ within Barber & Osgerby to handle this work, ‘an outward-facing brand even though as a studio we operate as a single group’. |

Words Will Wiles

Photography Felicity McCabe

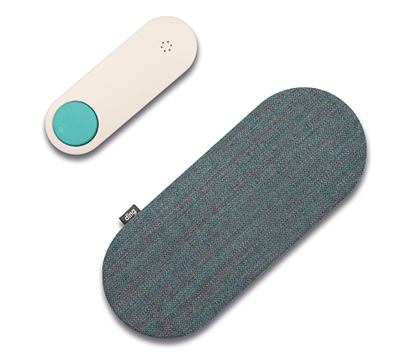

Above: The BleepBleeps Suzy Snooze – a combined baby monitor, night light and sleep trainer |

|

|

||

|

The Beeline bicycle compass, for which Map designed the compact casing |

||

|

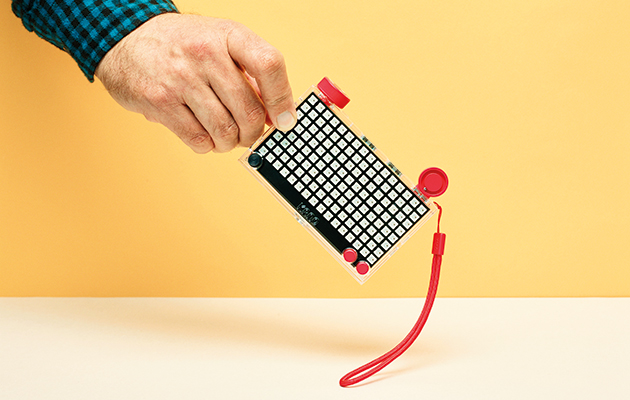

A lot of this work is speculative, ‘trying to shape how people will use technology in the future’. And it is all secret, all very, very secret. Beyond a few vague and general statements about concerns common to several companies – voice commands and artificial intelligence, for instance – Marshall can’t give any details. But this is just half of what Map does. The studio’s grounding in consultancy and working with established teams in large corporations has made it a specialist in collaboration. This has led to projects such as Sabi, a range of bathroom accessories aimed at older people. Fittings such as handles that help people with less mobility to get out of the tub generally have a utilitarian, medical appearance that comes with a degree of stigma. Sabi escapes that – Map worked with a biomechanical engineer to come up with a completely different profile, a sleek black ring. That kind of collaboration will be familiar to most design studios, but Map involves itself more intimately with some companies. That is what has led to Ding, a wireless doorbell. The door-mounted button is a white-and-blue lozenge with a distinct Barber & Osgerby parentage. More innovative is the chime, the bit that makes the noise, which resembles a chic speaker. This is ‘traditionally a white box with some holes in it to let the sound out,’ says Marshall, ‘[but] in this case it has had as much attention as the doorbell, if not more, in order to feel like something that goes in your home that you can put on a shelf in its own right. It’s simple and blends in, but also has a personality.’ But it is Ding’s background that makes it really fascinating. The idea came from two designers called John Nussey and Avril O’Neil, and it was funded on Kickstarter, the crowdfunding website for entrepreneurs. And it is not the only Kickstarter project Map has been involved in: Marshall estimates that they have had a hand in ‘seven or eight’, all developing ideas that originated outside the studio. Beeline was another, as was Map’s highest-profile project to date. Kano, a build-your-own computer kit for children, was a Kickstarter darling, raising $1.5 million and selling more than 100,000 units. Kano kits went on sale in Toys R Us for the first time for Christmas 2016.

The simple but sleek smartphone-enabled Ding doorbell and chime It is surely unusual for a well-established design consultancy with a client base of corporate titans to involve itself with so many embryonic companies. In part, the situation came about by happy accident – the studio was founded just as London’s hardware start-up scene was becoming established. But these clients are tiny, often no more than their founders, a fundraising website, and an idea. What does Map do for such companies? ‘It depends on who the founders are,’ Marshall says. ‘Some founders are really strong on the business side but have no technical knowledge … sometimes they are strong technically but have no business knowledge. What we try to do is get them from A to B. We have a lot of experience with manufacturing, we have experience with the digital side, particularly with industrial design.’ Which sounds like a fantastically valuable service for the lucky start-ups – but what does Map get out of it? There’s a fee, of course – necessarily lower than Google pays. To compensate, Map takes a ‘usually … very tiny’ stake in the business, either as a profit-sharing agreement or directly as equity. Then the firm finesses the product and helps bring it to market. So in essence, they are not too different to investors, putting expertise and experience into a company rather than money. This could be considered a novel form of venture capital – venture design? Venture realisation? Marshall bridles a little at the comparison. ‘I wouldn’t define it that way myself,’ he says. ‘[This is] a bit different to design firms like Frog or Ideo that do have a venture arm that makes cash investments in businesses, whereas what we do is more of a partnership.’ The model is better known in San Francisco, he notes, where companies such as Ammunition have been doing it for a decade. Clients come to Map, rather than the studio seeking them out, and they work together as a single team. |

||

|

Kano 2 Pixel Kit, a programmable LED grid designed to reflect the technology within |

||

|

Marshall stresses that the studio’s knack for bringing products to market doesn’t come from entrepreneurial cunning but from healthy design fundamentals. ‘The process is very make-focused,’ he says. ‘We have a workshop, we 3D-print things, we make things out of card. There’s a passion for making that extends throughout the studio. And for Map specifically, that extends beyond making for design to manufacturing. So we’re always trying to go to factories with clients and understand what the machine looks like, using that to influence the design process.’ Nevertheless, there’s undeniably a venturesome aspect to it, an element of risk unusual in a designer-client relationship. Kickstarter has seen some high-profile failures in recent years, with popular projects horribly delayed or simply failing to appear. Map’s business exposure is of course limited by its meat-and-drink work with technology companies. Still, they must be careful about who to partner with – how do they make that decision? ‘We don’t have a checklist but we’d definitely look at the people,’ says Marshall. ‘For me the first priority is, do we want to work with these people? Do we believe that the founders of this company will be able to launch this thing and bring it to market? So there’s a reputational thing. The second thing would be, is it a good idea? If we believe in it, it makes it a lot easier.’ Then come practical concerns, such as timing, and whether the studio has capacity – eight people work for Map full time, a total at present bolstered to 12 by freelancers and paid interns. Nevertheless, it’s an intriguing glimpse of a new and evolving direction for design studios: part industrial designer, part consultant, part investor. In the past, design was looked upon as a source of innovation. Designers could look upon a future in which they are also purveyors of practical expertise in a world bursting with ideas. |

||

|

The Seeker, a hand-held navigation device developed with creative agency AKQA |

||