![]()

Maja Ganszyniec quickly emerged as a leading figure in the ‘desert’ of noughties Warsaw design. Now she wants to coax Poland’s prolific but low-value furniture industry out of the wilderness, writes John Jervis

Talking to Maja Ganszyniec, it’s pretty clear why she reached the top – quite apart from design savvy and keen intelligence, she has an evangelical quality that has driven her rapid rise from Warsaw’s turn-of-the-century design scene (‘pretty much a desert’) to founding one of its most admired, and in-demand, studios, Studio Ganszyniec, a few years ago. It’s a startling achievement, yet one achieved under the radar, largely because her career has bypassed media-friendly, maker-type activities for the real deal: mass production.

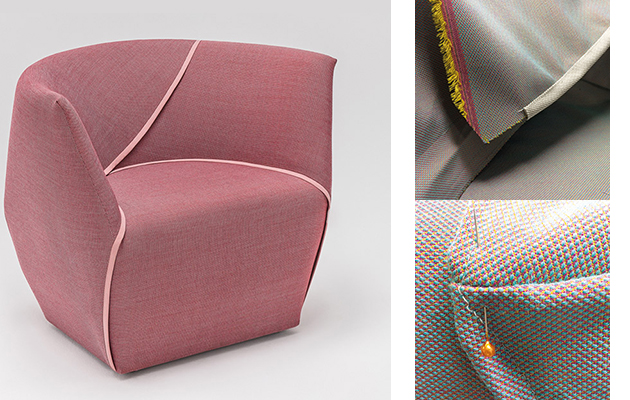

Maja Ganszyniec’s Ume chair for Polish brand Comforty, laucnched in 2016

Maja Ganszyniec’s Ume chair for Polish brand Comforty, laucnched in 2016

The route, inevitably, required leaving the country in 2002, via Atelier Mendini and Luca Scacchetti’s studio in Milan, to Ron Arad’s Design Products programme at the Royal College of Art in London in 2006. She headed back to Warsaw two years later with a couple of other ‘London Poles’ to set up Studio Kompott, just as their peers left the capital in the wake of the financial crash: ‘I was going against the stream and everyone’s saying, “You’re crazy. This is the wrong direction.” It was a pretty naïve decision.’ The ambition was to use the knowledge and skills learned from London and Milan’s contrasting design scenes – concept without manufacturing; manufacturing without concept – in the service of Poland’s enormous furniture industry. The third, fourth or fifth largest in the world, depending on who you talk to, it provides European brands with the quality that consumers often presume is Danish, Swedish or Italian. Transforming its innumerable factories-for-hire into design brands in their own right seemed an obvious and necessary step and offered her a far greater chance of seeing her furniture designs realised than London could possibly provide.

Studio Kompott lasted five years, kicking off the relationship with Ikea that has been vital to Ganszyniec. The Swedish firm has kept inviting her back to develop exciting ranges that focus on rapidly changing lifestyles – she spent the majority of last year at its Älmhult headquarters: ‘It’s kind of got out of control’. I ask if she worries about getting subsumed, or typecast, by this close collaboration. She acknowledges the possibility, but describes the opportunity as ‘almost impossible to turn down – it’s like a giant playground, with a huge amount of freedom, from ideas to materials.’ Small teams brainstorm concepts, consider questions they hope to answer and atmospheres they wish to create, then propose items that respond to their requirements: ‘It’s more important to ensure you produce the right things – the design of products is the last, last thing in the process.’ Not all designers have been so fortunate in their relations with Ikea, but Ganszyniec describes her experience at Älmhult – ‘the way of thinking, the culture’ – as a perfect match, and a lucky one, which has taught her a huge amount.

Comforty’s Ume chair’s efficient design involves just four stitching lines and one fold

Comforty’s Ume chair’s efficient design involves just four stitching lines and one fold

The design and business acumen she gained at Ikea has put Ganszyniec in good stead when pursuing her parallel career as a consultant, which she estimates now takes around 40 per cent of her time. Until recently, she was part of the Touchideas agency, often working on food brands with young entrepreneurs – exploring market niches, evolving names and packaging, refining launch strategies – while she waited for the furniture industry ‘to wake up’. It was not wasted time: ‘The food business is amazing – social changes, cultural changes always happen first in fast-moving consumer goods, and … eventually end up translating into less flexible fields.’ Unfortunately, furniture’s wake-up has been slow: ‘ten times slower than I expected’.

In terms of both design aesthetics and natural resources, Poland has long had much in common with Scandinavia, reinforced by decades of producing Nordic furniture. Ikea started manufacturing here back in 1961 and now uses over 300 Polish suppliers. Polish houses – including Ganszyniec’s childhood home – have been packed with Ikea rejects for generations. Yet, despite this industrial heft, barely a handful of homegrown designs were put into production in the final decades of communism. It was only when pent-up demand was unleashed in 1989 that astute companies seized the opportunity to sell Polish furniture, offering designs that Ganszyniec tactfully describes as basic: ‘These firms grew and grew because they had to furnish a country of 40 million people who couldn’t buy furniture for 30 years. It didn’t matter what it looked like, everybody bought it.’

Little has changed since. A (small) handful of impressive Polish firms have carved niches in the upper reaches of the market. One – Noti – will launch two new series by Ganszyniec this autumn. Another – Comforty – launched her Ume chair in 2016, an impressive feat of textile engineering with three strips of fabric wrapped tightly round its form, joined by just four stitching lines and one fold. She describes it as ‘almost a meditation’. But it is the huge, unfilled gap between the top and bottom ends of the market that Ganszyniec really wants to explore, and the timing seems right. Factory owners, long reluctant to change an approach that has worked well, are now handing their furniture empires to the next generation, and the realisation is dawning that a price-driven strategy will be unsustainable as international competition grows keener.

Maja Ganszyniec Användbar collection for Ikea was launched in 2016

Maja Ganszyniec Användbar collection for Ikea was launched in 2016

Meanwhile the sums that Polish consumers are willing to pay for well-designed furniture are finally rising. ‘People are travelling, they are realising that they want more – something unique, new, different from their neighbour, and something Polish – there’s a huge hunger out there.’ Shaping the future of Polish firms to meet this demand – advising them on marketing, branding, pricing, designs, ranges, online sales and more – is key to Ganszyniec’s practice.

Yet this aspect of her work takes a back seat on her website and, despite her pride in the undertaking (‘I’m growing customers, dressing them in different clothes, helping them escape the price race’), she is reluctant to name names. This reticence is understandable. These are huge, mass-market companies producing cheap products at the lower end of the market. For the time being, there is little glamour or kudos to be found in advising them.

Turning these firms round so that they achieve credibility is a long-term project – ‘five years perhaps’ – necessitating evolution in marketing and mindsets as much as in products. ‘It’s tough sometimes, coming into a meeting and telling people they have to change half of their portfolio – if they don’t they’re going to be dead in five years. You need to workshop with them, try and discover their values, ones they can talk about and believe in … People buy furniture not just because they need it, but because they want to be part of certain cultural expressions. They go for this brand or that brand because of its values, style, materials or philosophy – these are fine tones that you have to appreciate first, and then be very conscious of how to use them.’ There have been some disappointing stumbles along the way, but she is already finding that ‘miracles can happen’.

Only when she can list ten homegrown brands off the top of her head – ‘no one can do it yet’ – will Ganszyniec allow herself to start talking about Polish design in the abstract. Pronouncements of ‘design renaissances’ have tended to focus on contemporary interactions with folk art, resulting in beautiful products that sit well with international aficionados but have little wider reach. In Ganszyniec’s opinion, the perennial craft tag holds the scene back: ‘[The approach] tended to come from designers acting as makers, in part because they couldn’t really go into relationships with Polish brands, as there weren’t any. It was important to understand our roots – where we are, where we come from, our craftsmanship, our materials and colours – but this wasn’t design, it was craft. It was useful as a means to promote Polish design and culture. But it doesn’t really translate into anything modern. Tradition should be a stepping stone, not an end in itself.’

Ganszyniec’s Mellow sofa for Comforty was launched in 2016

Ganszyniec’s Mellow sofa for Comforty was launched in 2016

Developing a unique, ‘Polish’ point of view will take time, particularly given the dominance of Scandinavian design. The process is underway, aided by the success of the new Warsaw Home furniture fair, which has the potential to nurture the growing Central and Eastern European markets, but Ganszyniec feels that it is the sheer quantity and quality of manufacturing that provides the answer.

She offers an unexpected comparison with postwar Warsaw: ‘The city is not pretty – it was destroyed, flattened. This was a tragedy, but I think it was also one of the most positive things that could have happened, because there’s nothing to continue – you can start afresh. I think that’s why Warsaw right now is so vibrant and so exciting and so many things are happening … sometimes it’s easier to build something very futuristic and new on a desert.’

I end by asking if Ganszyniec has any concerns about importing the ethos of international design wholesale into Poland. After all it may not entirely be a blessing – that consumerism and homogeneity could replace older values of frugality and independence. She isn’t fazed: ‘I really hope what’s happening in fashion will not take place in furniture – fast fashion is a terrible, terrible thing. We’ve lost that creative spark, that efficiency that came from past shortages. Upcycling, swapping, recycling is the future, but that’s what we had back then, and we need to find it again.’ That may be an impossible circle to square, but I’m pretty sure that Ganszyniec has a better shot than most.

Subscribe to Icon to be the first to read profiles like this.