Lucienne Day in 1951.- ©Robin & Lucienne Day Foundation/photo: Studio Briggs

Lucienne Day in 1951.- ©Robin & Lucienne Day Foundation/photo: Studio Briggs

The enduring appeal of Lucienne Day’s post-war textiles owes as much to her organic, abstract graphics, as to her belief in affordable design for all, writes Icon editor Priya Khanchandani

Lucienne Day was Britain’s foremost textile designer during the post-war period. Her highly original textile designs included dress and furnishing fabrics, wallpapers, carpets and silk mosaics, featuring images of delicately expressed elements from nature such as flowers, plants, herbs and trees. Her aesthetic was clearly influenced by the abstract forms found in the work of painters such as Kandinsky, Miró and Klee.

Day grew up in the suburbs of London and studied at Croydon School of Art where she became acquainted with the Bauhaus and Swedish modernism. She went on to train as a textile designer at the Royal College of Art in 1937, following which she met her husband, the furniture designer Robin Day, also an RCA alum. To mark a decade since her death on 30th January 2010, and the anniversary of her birth on 5th January 1917, Icon looks back on her life through this selection of salient moments from her career.

Royal College of Art Diploma Show

Day’s contribution to the 1940 RCA Diploma Show – ©Robin & Lucienne Day Foundation

Day’s contribution to the 1940 RCA Diploma Show – ©Robin & Lucienne Day Foundation

A screen-printed linen inspired by a Chinese sculpture in the Victoria and Albert Museum was one of the pieces Day exhibited in her RCA Diploma Show in 1940. It featured a tile-like repeated pattern of equine heads that switch direction row by row, alternating with the horses’ bridles. She hand-block printed and screen printed the fabrics and displayed them on a stand designed by her husband, Robin Day, who also designed the accompanying chair, upholstered with her fabric.

Calyx screen-printed furnishing fabric

This ground-breaking fabric, designed as a furnishing textile for Heal’s in 1951, became Day’s most famous work. It created a radical new aesthetic in textile pattern. The irregular web of cups is exemplary of Day’s innovative representation of nature’s shapes and forms. The original colours were yellow, orange, black and white on an olive background. The pattern was screen printed on linen and became so successful that it won the gold medal at the Milan Triennale and the international award of the American Institute of Decorators.

The Festival of Britain

Day’s Calyx screen-printed fabric was designed for Heal’s and exhibited at the Festival of Britain – ©Robin & Lucienne Day Foundation

Day’s Calyx screen-printed fabric was designed for Heal’s and exhibited at the Festival of Britain – ©Robin & Lucienne Day Foundation

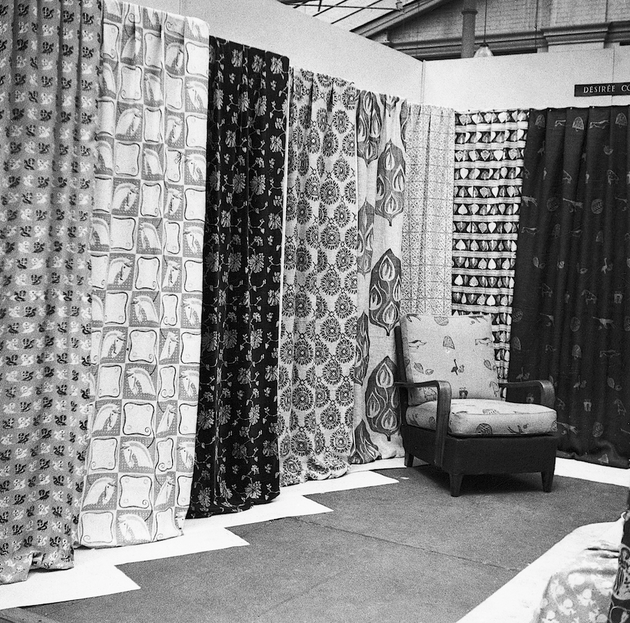

Day exhibited her textiles and wallpapers at the Homes and Gardens Pavilion of the Festival of Britain in 1951, where she collaborated with Cole & Son and John Line & Son. The aesthetic of this work reflected the post-war optimism of the time, with punchy colours and innovative, floating patterns and shapes. Calyx drew the most attention and went on to become a best-seller, outperforming the modest expectations initially set by Heal’s.

Heal’s commissions

Like her husband Robin Day, Lucienne believed in high-volume industrial production as a way to make good design accessible to consumers. She commented that she went into industrial design because she wanted people to ‘have good things at reasonable price.’ In the 1950s and 1960s she created a collection of up to six new designs a year for Heal’s alone. Overall, she went on to provide around 70 patterns for the brand. Calyx remains in production to this day.

John Lewis Partnership

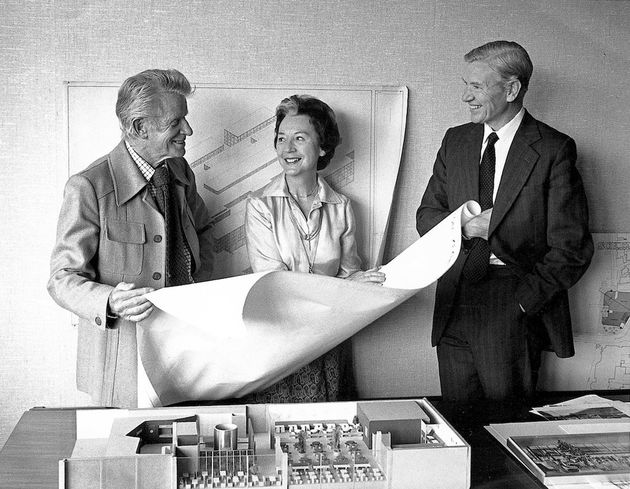

The Days worked as design consultants for John Lewis Partnership – ©Robin & Lucienne Day Foundation/photo: Trevor Fry

The Days worked as design consultants for John Lewis Partnership – ©Robin & Lucienne Day Foundation/photo: Trevor Fry

As joint design consultants for the John Lewis Partnership between 1962 and 1987, Lucienne and Robin Day played a key role in overseeing the introduction of a new house style. Much more than just a logo, this wide-ranging corporate identity affected every aspect of visual presentation, from colour schemes in buildings to packaging and price tags, which were codified in a new company design manual.

Silk mosaics

Aspects of the Sun silk mosaic (1990), Lucienne Day – ©Robin & Lucienne Day Foundation

Aspects of the Sun silk mosaic (1990), Lucienne Day – ©Robin & Lucienne Day Foundation

The main exception to Day’s commitment to reasonably priced design was the one-off silk mosaic compositions she focused on from the ‘80s onwards, which she described as being ‘more elitist.’ These intricate pieces used an innovative construction technique derived from patchwork, composed of 1cm squares and strips of silk. She justified this work on the basis of ‘staying creative’ and remarked that if she had continued working on printed textiles only, she wouldn’t have been able to deliver as successfully because, as she put it, ‘I was getting bored.’