This summer the former Museum of Childhood in Bethnal Green is to reopen as the Young V&A, with a creative focus and a design that children played a part in refining

Photography by GION featuring Heel-less Shoes by Noritaka Tatehana in collaboration with Ryūkо̄bо̄ ©︎ Edo Tokyo Kirari Project and Noritaka Tatehana

Photography by GION featuring Heel-less Shoes by Noritaka Tatehana in collaboration with Ryūkо̄bо̄ ©︎ Edo Tokyo Kirari Project and Noritaka Tatehana

Words by Joe Lloyd

Every year, dozens of major museums shutter for restoration, refurbishment and refreshment. When they reopen, they have an extra wing, or some new galleries carved out of previously under-utilised space, or a larger atrium and clearer wayfinding. Yet they are seldom reimagined.

When the Victoria & Albert Museum reopens its Bethnal Green satellite this July, however, it will do so as an almost completely different institution from that which closed in 2019. It will even have a change of name.

What was once the V&A Museum of Childhood will become the Young V&A – a linguistic shift that suggests a movement from a fixed collection of a historical theme to an active, present-facing institution.

Housed in a pioneering prefabricated iron structure initially erected and used for the V&A itself, the Young V&A is a prominent structure in a patch of east London remarkable for its Victorian architecture.

Photography by Mirko Kuzmanovic and Alamy Stock Photo featuring Paper Cranes at the Children’s Peace Monument to commemorate Sadako Sasaki and thousands of child victims of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima, Japan, 2017

Photography by Mirko Kuzmanovic and Alamy Stock Photo featuring Paper Cranes at the Children’s Peace Monument to commemorate Sadako Sasaki and thousands of child victims of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima, Japan, 2017

The previous Museum of Childhood exhibited a 33,000-strong collection of toys, objects and ephemera created for children. But it displayed them in a traditional manner. Rather than a museum for the young, it sometimes felt like a place for the old to reminisce about their own childhood.

The new Young V&A aims to be the first place of its kind: a museum that encourages design thinking and creativity in children and young people. It has been designed for allcomers between birth and early teen years. V&A director Tristram Hunt calls it ‘a flagship project investing in creativity with and for young people and their futures’.

The museum hopes to foster a new coterie of artists, makers and pioneers among what has already been dubbed Generation Alpha. To create the transformed museum, the V&A collaborated with two design studios: AOC Architecture and De Matos Ryan. AOC, which took the lead on the display design and museum visitor experience, is based a few minutes’ walk north of the museum.

The studio has completed a wide variety of projects involving community engagement, including the Crafts Council Gallery and Walworth Library in London. Active work includes a reimagination of the UK’s National Archives in Kew, the restoration of one of Europe’s oldest purpose-built cinemas in Devon and a new cultural hub in Kent.

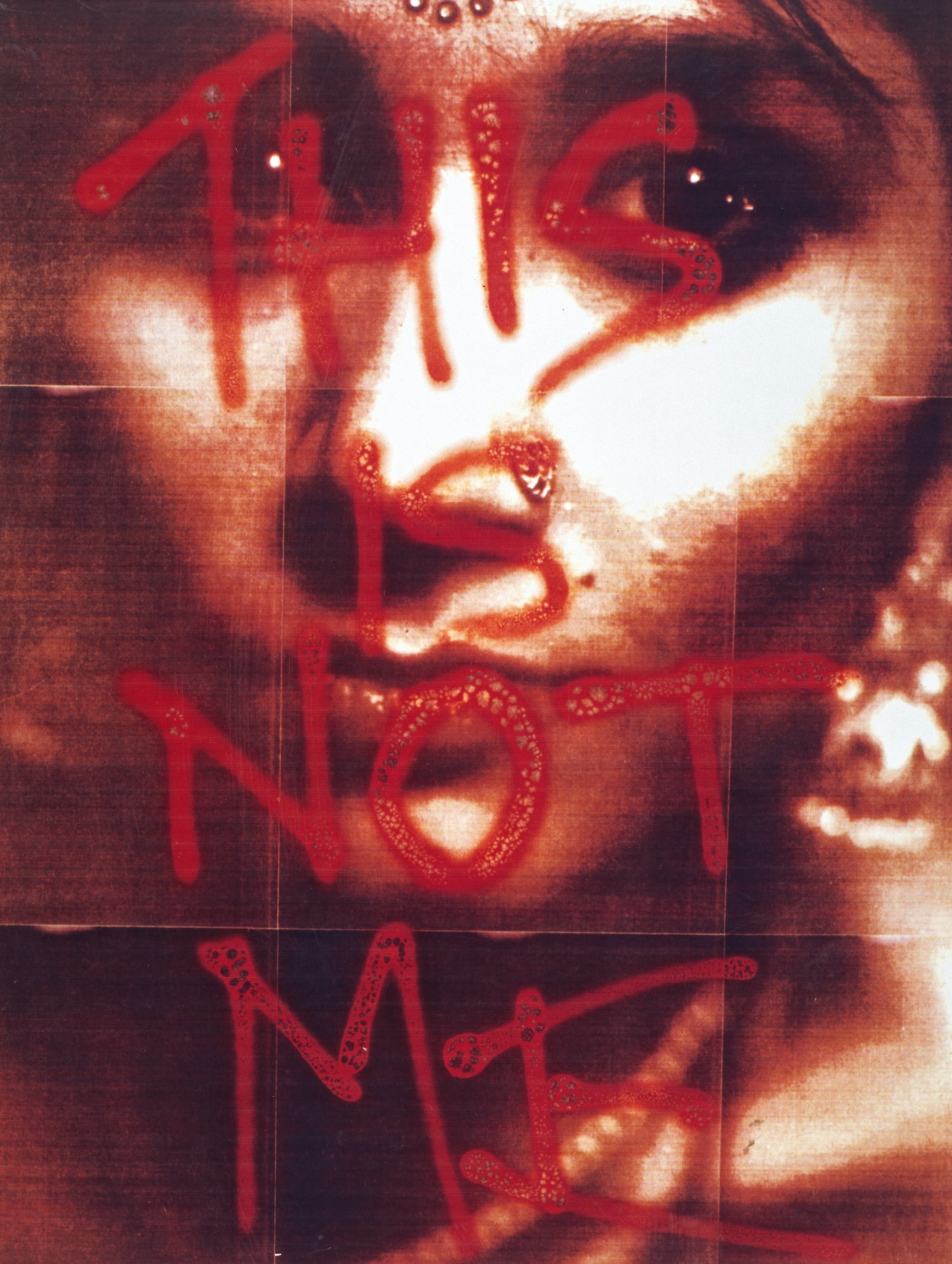

Photography courtesy of Chila Kumari Burman and Victoria and Albert Museum, London featuring This Is Not Me. Self-portrait by Chila Kumari Burman, 1992

Photography courtesy of Chila Kumari Burman and Victoria and Albert Museum, London featuring This Is Not Me. Self-portrait by Chila Kumari Burman, 1992

De Matos Ryan, which designed the new museum’s spatial layout and complete reorganisation including all of the lower ground museum spaces and community learning spaces, similarly has extensive experience with public projects. It has worked on St George’s Concert Hall in Bradford – the oldest building of its type in Britain – Sadler’s Wells and York Theatre Royal.

The practice is currently at work on Wonderlab, a new gallery at the National Railway Museum, York, which seeks to ‘excite, inspire and challenge young minds’. Its work at the V&A includes, among other things, a new accessible entrance, the decluttering of previous interventions and the enhancement of the museum’s outdoor spaces.

The Young V&A took its designers and curators seven years to plan and four to implement, at a cost of £13.5m. ‘Every aspect of Young V&A,’ writes V&A director of learning and national programmes Helen Charman, ‘has been developed with a rigorous eye to childhood developmental theories and practice, interwoven with the expertise of our curatorial, interpretation and learning teams to create experiences that will be social, relevant and inspiring.’

Uniquely, it was designed with the collaboration of its target. Children were consulted at all stages to ensure that the museum appealed and engaged them. There were over 40 co-design lessons with local schoolchildren, teachers and families. AOC held an Open Studio in 2019 to test and develop the museum.

Photography by Luke Walker Courtesy of Gallery Rosenfeld featuring Double Spiral by Keita Miyazaki

Photography by Luke Walker Courtesy of Gallery Rosenfeld featuring Double Spiral by Keita Miyazaki

It will thus be a ‘doing museum’ – one that encourages activity. There are three permanent galleries themed Imagine, Play and Design, which will showcase 2,000 objects from the V&A’s huge collections in a way that aims to spark the imagination. Areas and exhibits will include a construction zone, a 125-person performance and story- telling stage, playscapes and an open design studio.

There will be a ‘sensory environment’ for infants yet to learn to walk, a ‘finger skateboard park’ and an interactive Minecraft installation. There will also be a new Learning Centre, and galleries for temporary exhibitions. The first of these, Japan: Myths to Manga, will explore Japanese culture and animation.

Designing for children is notoriously difficult for even the best-informed and intentioned adults. The V&A and its partners have set themselves an enormous challenge. If they succeed, however, the Young V&A has the potential to redefine how children interact with museums, and nurture the creative impulse in generations to come.

Get a curated collection of design and architecture news in your inbox by signing up to our ICON Weekly newsletter