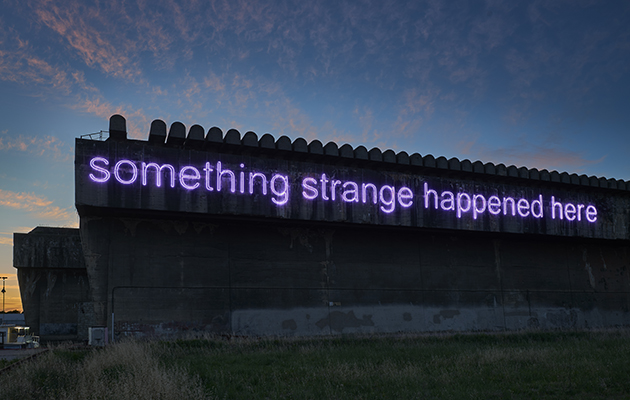

Something Strange Happened Here, by Daniel Firman in Nantes, 2017. Photo: Damien Aspe

Something Strange Happened Here, by Daniel Firman in Nantes, 2017. Photo: Damien Aspe

Now in its eight edition, Le Voyages à Nantes is a quirky arts festival that takes over the picturesque Breton city. Bryony Hancock followed the green line of the festival to discover what it’s all about.

If Eden were to exist, it would take the form of Nantes. Nestled among the canals of the Loire estuary, this Breton city is as idyllic as a metropolis gets. As a creative, colourful and progressive city that’s entrenched in history, Nantes relies on its established Socialist government to support its cultural initiatives. Yet, with France’s changing political landscape, this could be about to change.

Originally a port town responsible for half of the 18th-century French Atlantic slave trade, Nantes’ maritime commerce collapsed during the global recession of the 1970s. After shipyards closed in 1989, the former industrial hub was forced to adopt a different lifestyle, one of festivals, tourism and, at the centre of it all, a gargantuan mechanical elephant.

Yes, this sounds odd. So does a supersized yellow tape measure and a banana-shaped football pitch. However, these are commonplace for locals – thanks to an annual festival that colonises the town with artistic creations: Le Voyage à Nantes.

Éloge du pas de côté at Place du Bouffay by Philippe Ramette, in Nantes, 2018.

Éloge du pas de côté at Place du Bouffay by Philippe Ramette, in Nantes, 2018.

Le Voyage was devised in 2011 to promote cultural tourism and is orchestrated by grand-master Jean Blaise. Every July the city explodes for two months of installations that are connected by a painted green line that winds along 10 miles of pavement. Daniel Buren, Jean Bonichon and Cécile Bart are previous contributors.

The initiative followed a succession of projects concocted by Blaise and previous Nantais Mayor Jean-Marc Ayrault: the Allumées festival of 1990, the conversion of the abandoned LU biscuit factory into a club-cum-hammam and the biennale-style Estuaire programme. ‘Since the 1940s bombings we couldn’t capitalise on glamour, so the city had to become more intelligent, creative and humorous,’ explains Blaise. Once the government realised culture made money, Le Voyage was born.

But back to the elephant. Le Voyage is not just an annual festival; it is the coordinating body of all Nantes Metropole culture. Included is Les Machines de l’île – a mechanical Jules Verne-inspired dream world that transformed the former shipyard into a top attraction. Its three-tiered carousel, flying birds and giant walking elephant typifies Nantes’ quirky nature.

Le Voyage is an eclectic festival that takes over the entire city of Nantes. Photo: Evor

Le Voyage is an eclectic festival that takes over the entire city of Nantes. Photo: Evor

Seemingly, everyone appreciates the culture. ‘Nantais locals are happy to see their city being recognised as forward-thinking,’ says Blaise. Shopkeepers, restaurateurs and students all create art along the green line, displaying signs proclaiming ‘Je t’aime le Voyage!’ in their windows.

But Blaise’s vision wasn’t always widely accepted. ‘Lots of people were very suspicious when Le Voyage started,’ he recalls, ‘Although they remembered my previous projects, tourism professionals were sceptical that contemporary arts could produce revenue.’

Being the sixth largest city in France, Nantes boasts a repertoire of high-profile architecture. Jean Nouvel’s island front courthouse exerts civic power on the island’s waterfront. To the west of Les Machines lies Jean Prouvé’s station and south of Trentemoult stands Le Corbusier’s 1955 social housing block La Maison Radieuse. But the city is not resting on these laurels: by 2026 the urban landscape will be remodelled through a new phase of development.

Central Nantes will see a dramatic change thanks to mayor Johanna Rolland. Simulating Bordeaux, she plans to make the city car-free. By extending the green areas around the Château, cars will be pushed out in favour of trams, buses and cyclists. The current rail station is also being completely redesigned by Rudy Ricciotti architects. By 2020 its capacity will double and the front entrance will be extended to meet the Botanical Gardens across the road.

Celeste Boursier-Mougenot’s Aura, 2015. Photo: Blaise Adilon

Celeste Boursier-Mougenot’s Aura, 2015. Photo: Blaise Adilon

Further still, the island poses more opportunity for architectural development. In the Southern brownfield site, the M.I.N. Wholesale Market will relocate in favour of the new University Hospital, which will provide a 225,000 m² Healthcare District. Last September saw the opening of Franklin Azzi’s Nantes Higher School of Fine Art in the Creation Quarter – a restructuring of the old Alstom warehouses leftover from the shipbuilding days. The original metal frame has been kept, with studios, exhibition spaces and workshops being arranged around a central walkway.

Further down the Loire, the Bas-Chantenay district will witness a 150-hectare urban renewal project. At the centre will stand Nantes’ most eccentric project: the 50m wide and 35m high Heron Tree devised by Les Machines. After visitors ascend the double-helix staircases inside the trunk, two giant mechanical herons will embark on circular flights atop the twenty-two steel branches. Vegetation will take root within the frame and all plants will be watered with harvested rain.

As bizarre as the Heron Tree sounds, this shrewd fascination with play and public spaces is what makes Nantes so accessible. After two days one already feels included in the city’s clockwork modus operandi. From the riverside Ping Pong Park to Claude Ponti’s oversized park benches, people everywhere are enjoying the space created for them.

But the city wants more. In anticipation of France’s 2023 Rugby World Cup and 2024 Summer Olympics, the new Yellopark football stadium, designed by Dominique Perrault, will raise Nantes to a global standard. Also, the hotly debated topic of the Grand Ouest Airport in Notre-Dame-des-Landes has been circulating the news since the 1970s. Following mass protests, the project was scrapped in January 2018 but the issue is not yet resolved; on my departure activists besieged the current Nantes Atlantique Airport with billboards.

Daniel Firman’s 2013 Drone Project Photo: Blaise Adilon

Daniel Firman’s 2013 Drone Project Photo: Blaise Adilon

It’s clear the city has its own identity. But this wouldn’t be possible if not for Jean Blaise’s foresight in the 1980s, not to mention three decades of political stability to boot. What will happen when he leaves? ‘I hope Nantes will continue through its own personality. Cities are like people; they must find their own way of progressing,’ says Blaise. Street rumours hint that he will only stay for a few more years. Furthermore, Johanna Rolland faces a potential usurping at the next mayoral poll after last year’s presidential elections saw many Socialists defect to support centrist Emmanuel Macron.

Nonetheless, people do not seem concerned. Cultural tourism is so intrinsic to Nantes’ success that even the opposition can’t deny its fiscal benefits. As architecture springs up everywhere, population steadily increases and more artists flock to reap creative rewards, it seems this small city really is the land of all possibility.