Architect and designer Jo Nagasaki used paint, bleach and on Solid Textile Board.

Architect and designer Jo Nagasaki used paint, bleach and on Solid Textile Board.

Kvadrat is launching Solid Textile Board – a hard, flexible and, crucially, reusable material made purely from end-of-life fabrics and offcuts. Could this circular process spell the end of textile waste, asks Joe Lloyd. Images by Casper Sejersen.

First up, the good news: across the West at least, the quantity of waste recycling has been steadily increasing since the turn of the millennium. But there’s a rub: much of it may have no long-term environmental benefit. The majority of recycled materials either, like paper, gradually decline in quality or are placed into inferior products, often those whose other components cannot be reused. This process, downcycling, simply defers the date of a material’s destruction or disposal.

There is an alternative, named – unsurprisingly – upcycling, in which waste materials are re-used for products of equal or higher value. Though natural degradation of materials can make this difficult, it enables resources to be conserved much longer. ‘Everything,’ says Wickie Meier Engström, the CEO of the Danish brand Really, ‘that we take out of the system has a value, and we need to capture that value for as long as possible.’

Really, established in 2013 and based in Copenhagen, is the producer of the Solid Textile Board, a hard yet flexible material created from textiles and bicomponent plastic. Since the start of 2017, it has been an official partner of Kvadrat, a company with an enviable reputation for creating design-quality textiles. In a paradigmatic example of upcycling, Really takes disused items from the fashion and textile industries and turns them into a resource for furniture designers. Clothes and sheets – items that often have a short usable lifespan – are transformed into design objects that can be used for a much longer duration. And, if a product crafted from the board is damaged over time or outlives its function, it can be ground down and put through the process again, to create a material with the same quality as its first iteration: a system known as a circular economy.

Raw Edges used CNC engraving to create furniture with a tapering pattern.

Raw Edges used CNC engraving to create furniture with a tapering pattern.

Really was founded by Meier Engström, Klaus Samsøe and Ole Smedegaard. Samsøe, one half of the clothing label Samsøe & Samsøe, had long been interested in the re-use of material. A 2009 collaboration with the large-scale launderer De Forenede Dampvaskerie saw him forge garments out of discarded bed linen. Galvanised but frustrated by the slow pace of garment design, he began to experiment with ways to transform used fabrics into a solid material. Two years later, after working on prototypes at the Danish Technological Institute, he presented his work to Meier Engström – then a sustainable design professor in Berlin and an innovation consultant – who had become especially conscious of textile waste during her previous work in the fashion industry. The business strategist Smedegaard joined in 2012, and soon after Really came into being, albeit with the working moniker of Sustainable Hedonism. A snappier name soon became apparent. ‘At the time,’ remembers Meier Engström, ‘everything to do with recycling was pre- xed re-this and re-that. We didn’t want to be part of that. And then one of us said, why don’t we call it ‘Really’, as in ‘this is really what we’re doing?’

The company’s initial pitch to investors – From Fashion to Furniture – applies as much to Meier Engström and Samsøe’s career paths as their product. Well aware of their distance from furniture design spheres and the signi cant amount of R&D required, the trio sought partners. ‘We needed the muscles of someone bigger,’ says Meier Engström, ‘and we wanted to work with the change-makers of the world. So, being based in Denmark, we naturally thought of Kvadrat.’ After several years of working together to develop the material and ready the supply chain, Kvadrat purchased a 52 per cent stake in Really at the end of 2016 and the two became partners. Kvadrat has a strong record of sustainable manufacture. Its Revive textile, available since 2009, uses a yarn composed from discarded plastic bottles, an example of upcycling a material from mass-market to more rarefied use. The addition of Really to its stable allows the company to upcycle its own off cuts.

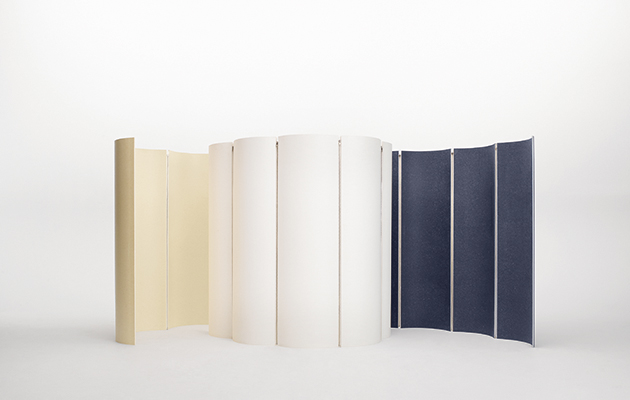

Playing with the acoustic qualities of the material, Jonathan Olivares created a sound-softening room divider.

Playing with the acoustic qualities of the material, Jonathan Olivares created a sound-softening room divider.

There is something of the alchemic about Really’s process. Disused fabrics, largely taken from industrial laundries and fabric recyclers as well as Kvadrat’s selvedges, are shredded then milled into tiny granular fibres – ‘the smaller we grind it,’ explains Troels Theilby, Really’s production manager, ‘the more control we have over how it looks.’ These are mixed with polypropylene and polyethylene bicomponent fibres. This pulp is air-laid – a technique pioneered by the mid-century Danish inventor Karl Krøyer for making paper without using water – in a steamer, to create mats of a fluffy but firm appearance. More than half of these, which Theilby calls the ‘core material’, are made from white cotton, and have a snowy hue. The others, about half as thick, are made from the most common shades of cottons and wools, such as the blue cotton from denim. Three sheets of the core material are then sandwiched between two of the thinner ones and smoothed out under paper-thin plastic sheaths.

The piles are then placed into a compressor – a formidable 1960s machine resembling some sinister pipe organ – heated to around 140oC and slowly pressed down. ‘We use 1,000 tonnes of pressure, says Theilby. ‘That’s a whole lot of elephants.’ When they emerge, the sheets have slimmed down by a factor of eight, and changed texture completely to become a solid board. And therein lies the alchemy: running one’s hand along it, it feels a little like a light wood or a sturdier MDF, but smoother. It has a subtle sheen, and a mild speckled pattern. Without foreknowledge, it would be di cult to conceive that this substance was previously soft textile.

British designer Benjamin Hubert create Layer, a range of wall-mounted storage and shelf units

British designer Benjamin Hubert create Layer, a range of wall-mounted storage and shelf units

Contriving this new material was an arduous undertaking. It took four years from commencing production in 2013 to the Solid Wood Board’s launch in 2017. ‘There were a lot of unknowns,’ recalls Theilby. ‘If we saw any variation, we had to test it out ourselves. We couldn’t go out and ask an expert.’ From the beginning, water – used in binding MDF – was out, because it would be absorbed by the textile and cause it to swell. Attempts to use glue saw the textile pulp gloop together in clumps. ‘So we tried various other processes,’ says Meier Engström, ‘but even when the material was rm, the aesthetic qualities were poor. And that’s important for us – we wanted a quality material that designers would want to work with.’ Even once the material was settled, elements of the production caused problems. Once, when too many layers of the board were placed into the cutting machine, the factory’s vacuum cup system was overloaded and caught fire.

As a new material, the Solid Wood Board has traits that are yet to be unlocked. When the British designer Max Lamb worked on Really’s first Milan exhibition last year, he discovered that its non-woven composition allows it to be bent easily without breakage. Several of the 12 benches he designed for the show made use of this property to display curvaceous, organic shapes. For this year’s Salone, the company has invited seven designers and design groups to engender a range of products, to be shown in an exhibition curated by Kvadrat’s Njusja de Gier and the London-based designer and curator Jane Withers. ‘We chose,’ says de Gier, ‘designers with an investigative approach, and who were interested in the properties of materials.’

Claesson Koivisto Rune Architects created this modular system shelf and room divider.

Claesson Koivisto Rune Architects created this modular system shelf and room divider.

These chosen practitioners have made a strong case for the material’s aesthetic multi-functionalism, while drawing on its own distinct qualities. Several, including Front and Jonathan Olivares, have continued Lamb’s exploration of curving, producing wavy, curtain-like storage systems and acoustic room dividers respectively. For a set of chairs, Jo Nagasaki has coloured, sanded and bleached the board to display four very different veneers, while Raw Edges has engraved it with a delicate pattern that has a hint of art nouveau glasswork about it and shaped it into benches, shelves and co ee tables. The architect Claesson Koivisto Rune has produced a modular shelf system deploying each of the material’s standard colourways, and Benjamin Hubert has fabricated adaptable wall curving. The most oblique piece comes from Christien Meindertsma, who worked with Really last year on a book and lm. Her Acoustic Fur places magnets within the cream-coloured strands of the pre-compressed material and attaches them to a wall to create a patterning that resembles sheep-hair.

In a booklet produced for the 2017 Salone launch, de Gier and Withers wrote that ‘the alliance between critical design and commerce raises awkward questions’. In Really’s case, given the evident environmental weal of its products, such queries seem barely worth asking. The metamorphosis of abandoned textiles into a meritorious design material is something to be applauded. And in design as in fashion, the high-end can serve as the stylistic driver for the mass market. With luck, Really’s example will di use down, encouraging other companies to attempt their own circular models before it is too late.