|

|

||

|

The London-based designer’s films offer a glimpse into a nightmarish sci-fi future in which every surface, appliance and inch of peripheral vision fizzes with data – an onslaught that might be just a couple of years away. Designers, he says, must shape this world – or be shaped by it Keiichi Matsuda’s mind is in the near future. The London-based designer, best known for creating the Prism installation at the V&A for the London Design Festival in 2012, makes short films that speculate on life five to ten years from now. The series shows everyday life densely stuffed with information via a virtual overlay: in the course of making a cup of tea or driving to work, logos and messages endlessly appear and disappear in your field of vision, like a browser infested with pop-ups. Matsuda’s speculations show our appliances, homes and bodies surrounded by a digital “aura” – an ever-present cloud of data that accompanies us and interacts with those of others. He argues that augmented reality (AR), a technology that layers real-world objects with digital properties, will soon allow us to customise the world around us, to simulate streets, cities and architecture according to our whims, editing and curating environments as we do our social media profiles. Whether that’s your idea of a superficial hell or virtual fantasy, Matsuda argues his brand of hyper-reality is not so far-fetched: just an extrapolation of the personal technology we use now. ICON: Your films show our future lives saturated with inescapable streams of information, advertising and data. Is this really where we’re heading? And is it a good thing? Keiichi Matsuda: The future is currently being manufactured in labs and boardrooms all over the world. People in power have recognised the potential of data, and are putting all their money on the project of merging the digital and physical, so for me it’s not a matter of if it will happen, but when. We’re constantly being sold visions by the big tech companies about how technology’s going to solve all our problems. We know from experience that doesn’t happen, and that it creates more than a few of its own. It would be naive to think that these corporate, utopian visions will deliver on their promises. But that doesn’t mean that we should abandon utopia and turn to dystopia. If you’ve committed to one of these paths, then you’ve cut yourself off from the possibilities of the other. I’m an advocate of critical design: using design as a tool to raise questions, and provoking debate about both the positive and negative outcomes. VIDEO: HYPER-REALITY (2016) |

Words Riya Patel

Photograph Leon Chew

Above: Keiichi Matsuda in his studio |

|

|

||

|

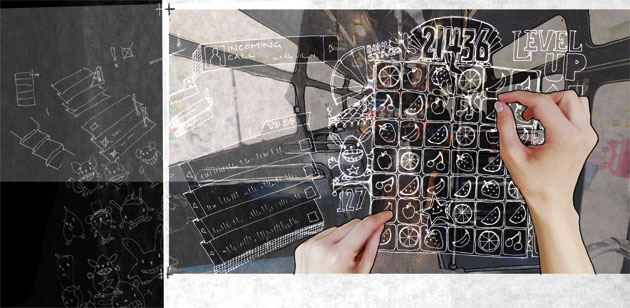

Added to this article in June 2016, Matsuda’s latest film presents a provocative and kaleidoscopic new vision of the future, where physical and virtual realities have merged, and the city is saturated in media |

||

|

ICON: But your films are generally positive, at least in that they elicit excitement about what technology can do. KM: Yeah, although I feel like part of my work serves to recognise and highlight the discomfort we feel towards technology, there’s another part that tries to feel out new possibilities. Trying to think around these things has been like walking a tightrope though. At every stage it felt like there were areas that would be wide open to exploitation for profit. But there is a potential for something positive. Digital media has a democratising effect. Now, everyone has a camera in their phone, and can produce and distribute their own content. It means that suddenly everyone can be both a consumer and creator of culture. I was thinking about how that could be applied to architecture, to the creation of space. What if an ordinary person could not only customise their own house, but their own street? What if they could collaborate with the local community? Chinatowns are a really interesting comparison here – people from a certain culture coming to a city and customising an area based on their world view. I think of the augmented city as having thousands of Chinatowns, each community with its own way of seeing. It could lead to localised explosions of creative culture, as areas develop their own distinct styles. Since you’re not restricted by cost or gravity, the augmented cityscapes could be really wild. And that could inspire a kind of augmented reality tourism industry, where people would travel to see these amazing environments. What we’re really talking about is space itself becoming a form of media, and from that emerging a new form of cultural expression. It’s the opposite of the globalised homogenisation we feared at the end of the last century. It would allow people to be in control of their city rather than developers and landowners, which I think is something interesting to consider. VIDEO: AUGMENTED CITY 3D (2010) |

|

|

|

This film takes the scenario outdoors, showing how digital technology might allow us to customise and interact with our environments like never before |

||

|

ICON: That’s the virtual realm, which doesn’t have to address the problems of the real city. You started out studying at the Bartlett, where you said you became frustrated that the practice of architecture fails to acknowledge the way the world is changing. KM: A lot of architects completely shun any idea of this digital stuff happening. They won’t even admit mobile phones exist. And they’ll still create spaces that are expressly designed for one purpose. You can see already that people don’t occupy spaces like that. If you go to a coffee shop, you don’t just have to drink coffee. You can use it for a meeting room, to meet friends, or to study alone. Most architects would have never thought to design that kind of space. People play games on the train on their way to work; they don’t need to do that in an arcade any more. We’re always taught in architecture that form follows function, that the design should support the intended function of a space. But mobile devices allow function to be decided instantaneously by whoever is in that space, so it’s important that we reconsider that relationship. A lot of the time it’s tech manufacturers or developers really dictating how we use our space, not architects. In the next decade, we’ll start to see a lot more flexible environments that can support multiple activities. There’s architectural precedent for it: Cedric Price was designing the Fun Palace in the 1960s. The other thing is that technology doesn’t always sit well with the ambitions of architects. It doesn’t have the same sense of permanence that architects want architecture to have. Tech exists on a different timescale, so it’s hard to integrate meaningfully with physical architecture. No one wants their smart home or smart city to become obsolete in five years. I like to think my films come from an architecture discipline but have become something else – something much more dynamic and responsive to events, more in line with game design than traditional architecture. As the possibilities of technology encroach on the domain of architecture, I think a new discipline will grow out of it. Even if it’s not augmented reality that takes off, there are plenty of other technologies with the same issues, and there’ll be a need for a designer able to reconcile the digital and the physical. VIDEO: DOMESTIC ROBOCOP (2010) |

||

|

Still from Augmented (Hyper) Reality (2010), Matsuda’s first excursion into AR |

||

|

ICON: How would we see the digital overlay? Through a device? KM: I try to stay away from hardware. A lot of people ask me how it would work: “Are you wearing glasses? Or a contact lens?” In a way it doesn’t really matter. The future I’m trying to prepare for has ubiquitous, always-on augmented reality. But AR is just an interface, a way of presenting that information. It’s just the final link in a huge chain of technologies that all depend on each other, so we could replace the augmented reality with smart surfaces and the questions would still be relevant. There are a lot of emerging technologies that people are getting excited about and pouring a lot of money into, but they are heading in a direction that no one has really defined. It’s a vague idea based on some adverts, or utopian future concepts that big tech companies have made. My aim is to crystallise that vision, and give people the tools to question if that’s really what they want. |

||

|

Still from Augmented (Hyper) Reality (2010), Matsuda’s first excursion into AR

Stills from Domestic Robocop (2010), part of the Augmented (Hyper) Reality series |

||

|

ICON: Where does the look of the films come from? KM:I guess part of it is that I’m really bored of this Dieter Rams/Jony Ive world of design and I just think there must be another way. A lot of people ask me whether I think this kind of saturation, this hyper-dense situation, is comfortable. I’m trying to make a very different aesthetic and see how we’d deal with that. But you know, it’s also a taste thing. |

||

|

Stills from Augmented City 3D (2010) |

||

|

ICON: The films you are making now are set in Medellín, Colombia. Why? KM: There are so many films or adverts or images about the future of London or Los Angeles or New York. Our consumer technology is also geared towards white, male, middle-class, American or northern European city dwellers. When you take it out of its intended context I think that it’s easier to get under the skin of technology, and see its rough edges. I first went to Medellín two years ago to speak at a conference called Fractal. It was the most amazing forum to talk about really speculative ideas. And it was possible to do that in Medellín because of its incredibly dark history. It has a very violent past, with a bad image that’s based on drugs and gangs. That has been changing in the last ten years and now a lot of work is being done in social and urban regeneration. The city is fighting hard to find a new future. So it’s really exciting to be somewhere that is in the process of reinvention. |

||

|

Stills from Augmented (Hyper) Reality (2010) |

||

|

ICON: Your films are very believable. They make you question if you want to be bombarded by all this information, these signs and signals. But then you start to realise that actually a lot of it is all around us anyway. KM: We’re not very good at recognising the characteristics of our present. The technology we see in TV and film is always around ten years behind; for example, we’re only just seeing people using social media on screen. Social media has been a part of life for a decade, but people didn’t know how to implement it in a film. One way you can get around that is by changing the context. George Orwell did this brilliantly: by taking you out of your world, he created a distance that allows you to see things in your own life more clearly. So although my film Hyper-Reality is ostensibly about ten years in the future, part of it is trying to understand how we live our lives right now, and giving people the distance to reflect on that.

Still from the forthcoming Hyper-Reality (2015) ICON: What stands between us and a future like this? KM: What changes much slower than the vector of technology is the vector of culture – our adoption of technology and our understanding of how we would use it. We’re being groomed by the tech companies to be ready for these things. And even this issue of Icon is complicit: priming people to be ready for a type of future that is being simultaneously sold to us. We’re still behind though, which can make people feel frightened about their role in the future. Technology, engineering and science are unstoppable linear vectors, that keep pushing the limits and boundaries of what’s possible. But the vector of culture is different. It moves in unpredictable ways. The role of designers now, especially ones dealing with the digital and the physical, is about trying to reconcile this divide between technology and culture. Part of this is solving problems, but an equally important and often neglected part is about exposing problems, trying to understand the issues and the consequences of emerging technologies. I often get scared about the motives of technology, and it sometimes seems that we just buy into things without considering their impact on our lives. Designers can occupy an essential role in making sure that progress still improves our everyday lives, that technology still serves us in a useful and meaningful way. If we can succeed, then technology will become an increasingly positive force in our lives. It used to be that science and science fiction had a relationship. Science would have an amazing leap that all the writers would get excited about and expose new possibilities and pitfalls, which would then inspire the scientists. It was a beautiful symbiotic system, which used culture as an active agent in the creation of the future. Unfortunately it’s mostly forgotten now, but I would love to be part of its revival. I think it would lead to a world that’s more considered and understood, a future that we’ve defined ourselves, rather than by the invisible hand of the market. This article first appeared in Icon’s December 2014 issue: Data, under the headline “Total digital overload”. Buy back issues or subscribe to the magazine for more like this. Keiichi Matsuda’s new series of films, Hyper-Reality, will be released this year. You can watch two of his Augmented Hyper-Reality films embedded above or by clicking here OTHER ARTICLES FROM OUR DATA ISSUE: |

||

|

Stills from Augmented City 3D (2010) |

||