|

Fluorescent DayGlo paints were invented by two Californian brothers in the quest to perfect their magic show. Having left a mark on everything from psychedelia to health and safety, the colours are still made using the same processes, and in the same street, as they were 70 years ago In a rather bland, brick building on the outskirts of Cleveland, Ohio, 4.5 million pounds of fluorescent pigment are manufactured every year. Inside, the factory floor is a messy explosion of luminescent, psychedelic colour. Everything – all the weathered industrial equipment and looping pipes, every shovel and brush – is brilliantly coated in the DayGlo Color Corporation’s trademark hues: Saturn Yellow, Blaze Orange, Aurora Pink, Neon Red, Corona Magenta, Signal Green and Horizon Blue. These vibrant colours end up being used on everything from laundry detergent to traffic cones, from toys to construction jackets. Look around: our world is saturated with DayGlo. These synthetic fluorescents have been with us much longer than one might expect. DayGlo was invented in the 1930s by Robert and Joseph Switzer, the teenage sons of a pharmacist in Berkeley, California. Joseph Switzer was an amateur magician, especially interested in the use of “black art”, whereby ultraviolet lights (known as black lights) are used to make fluorescent objects miraculously appear and disappear on a darkened stage. One night, the two brothers explored their father’s drugstore with the ultraviolet light Joseph used for his tricks. Certain chemicals, they were fascinated to discover, glowed incredibly brightly under the black light. Murine eye wash was particularly luminescent, and when they mixed it in the darkroom with an alcohol solution of white shellac paint, the result was their first good fluorescent yellow.

Waste bin or pop art? Although it appeared white to the naked eye, under ultraviolet light it shone with the intensity we associate with its visible successor: DayGlo. In 1934, the brothers set up Ultra Violet Laboratories. Despite the grand name, their business was a homey affair. The laboratory was their mother’s laundry room, their tools her “Mixmaster” and other kitchen utensils. They charged other magicians the princely sum of $10 a pint for their special Glo-Craft paint (it was so expensive that customers suspected that it must contain radium). In the summer of 1935, the Switzer brothers moved to Cleveland, Ohio, where the DayGlo Color Corporation is still based, to work for a subsidiary of Warner Brothers. Theatre foyers were especially well suited to the hologram effect of their “Midnight Paintings”, whereby a scene would change dramatically with the shift from white to black light. But such effects were less successful on billboards or in windows, where there were contaminating light sources and the colours were liable to fade. The brothers began to search for a luminous paint that was visible to the naked eye and, in 1936, by mixing fluorescent and natural pigments, they created the first DayGlo lithographic inks, available in a range of psychedelic colours.

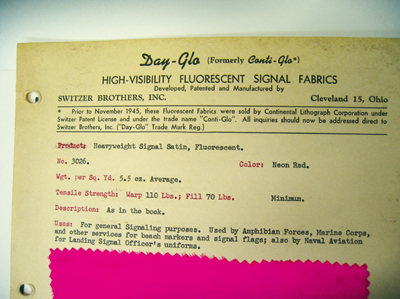

Neon-red fabric destined for military use The radiant quality of the colours was a result of the chemical conversion of ultraviolet light into visible light within the pigment itself. The pigments absorbed light frequencies that were both visible and invisible to the human eye and re-emitted them to produce intense colours that appeared to glow, even in daylight. Initially, the neon colours were prone, like their predecessors, to fade rapidly. The brothers sought to overcome these limitations, and conducted a battery of tests on swatches that Robert Switzer cut from his wife’s wedding dress. Eventually they found a “daylight fluorescent” that held. “Switzer Sunbonded DayGlo” was first used on lobby cards to advertise films. The real success of DayGlo colours, though, was their marketing as colours of safety: “Fluorescent color is seen 75 per cent sooner than conventional colors!”, claimed their advertising material of the time. “Fluorescent color is three times brighter than regular color! Your eyes go back to fluorescent color for a second look 59 per cent of the time!”

A factory floor bears the marks of the Blaze Orange mixing process The US military spent $12 million on DayGlo fabric during the Second World War, making the Switzer brothers rich beyond their dreams. Fluorescent safety materials were first used in the deserts of north Africa so that ground forces could signal to Allied dive bombers and avoid friendly fire; fluorescent paddles were used on aircraft carriers to help planes land in low-visibility conditions and at night, something that Japanese pilots were unable to do. Training aircraft were painted Blaze Orange to avoid mid-air collisions. After the war, the DayGlo-ification of the world began in earnest. By summer 1951, Time magazine noted that “adolescents were fluorescent from coast to coast, as Switzer’s ‘DayGlo’ clothes became the newest fad”: Items: shocking pink caps with kelly green brims, electric blue ties striped with cerise, black cowpoke shirts embroidered in fluorescent green. Some youngsters wore one sock of glowing orange, one of rasping raspberry, topped them off with high-visibility shoelaces in contrasting colors … women were buying brilliant tangerine panties; matching illuminated brassieres were on the way.

Blaze Orange pigment – it will be mixed with plastic resin to create paints and inks Subsequently, hippies, pop artists and punks all staked a claim to Switzer colours. Joseph Switzer, who never lost his penchant for showmanship, wore suits made of fluorescent satin and drove a Ford Thunderbird painted in DayGlo. He looked less like an industrial entrepreneur than one of Ken Kesey’s Merry Pranksters, whose legendary bus was also decorated using the Switzers’ invention. Even the introverted Robert, whose preferred attire was chequered jackets and bow ties, could not resist the occasional opportunity to flaunt his new-found fame by going to fancy-dress parties as a DayGlo pirate. Fluorescent dust spewed out of the smokestacks of the company’s busy factory in Cleveland, turning the city DayGlo. Robert Switzer’s son, Paul, remembered: “My father used to have many complaints from the residential neighborhood because, for example, all their laundry had been contaminated with fluorescent orange.” The dust was toxic –DayGlo’s secret recipe used to contain formaldehyde, a carcinogenic ingredient used by embalmers. Joseph Switzer died in 1973, at the height of the DayGlo era, but Robert, a keen environmentalist, installed special filters on the factory chimneys to minimise pollutants in the late 1970s, before selling the company in 1985 – he finally passed away in 1997.

The DayGlo palette has grown over the years At the Cleveland facility’s noisy dry pigment plant, the process is much the same as it has been for 70 years. Fluorescent dyes are combined with a special plastic resin and melted down in a huge reactor at 160ºC until it reaches the consistency of taffy. This mixture is then cooled to a solid in huge bins, and ground to an incredibly fine powder (each particle is the size of a blood cell), which seems to get everywhere. On the other side of the street, in the original 1940s facility, is the wet paint plant, where printers’ inks are made, pigments are tested, and new products explored. In 2012 the psychedelic factory, so associated with the LSD generation, was made a National Historic Chemical Landmark. The irony is that DayGlo’s supposedly life-saving hues are now so ubiquitous – worn by everyone from road sweepers and lollypop ladies to cyclists and construction workers – that we barely notice as they clamour for our attention. The photographer Stephen Gill dons a high-visibility jacket when he doesn’t want to draw attention to himself, and has documented the many workers forced to wear DayGlo attire in This article first appeared in Icon 142: Colour. Buy back issues or subscribe to the magazine for more like this |

Words Christopher Turner

Photographs Chris Barton and Jane Gavan |

|

|