|

|

||

|

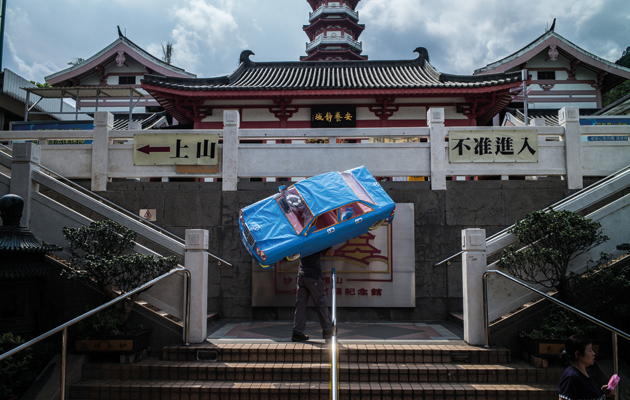

Furniture brands are getting tough on copyright, and UK law has been tightened to protect designers’ work after their death. But could this crackdown actually stifle creativity? East Asian funerary tradition dictates that the death of a loved one is accompanied by the burning of paper money, ensuring an affluent afterlife for the deceased. In Hong Kong, funeral shop owners have become increasingly creative in their interpretation of the ritual, stocking shelves with paper replicas of luxury goods – from sports cars to Gucci handbags – in addition to the customary paper money. When Gucci discovered these paper copies earlier this year, it initially threatened legal action for trademark violation, before later apologising for overreacting. As this example illustrates, not only has owning and protecting a product become increasingly difficult in the digital world, but the idea of intellectual property itself is ripe for a rethink. Rather than considering copying to be an underlying foundation of all cultural endeavour, Western rights law is taking an increasingly protectionist approach towards intellectual property. In Britain, for example, July 2016 marked the start of a six-month grace period for furniture reproduction companies to sell off remaining stock of their so-far legally produced replicas of designs like Arne Jacobsen lamps and Mies van der Rohe chairs. This is because the repeal this year of section 52 of the Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 has, thanks in large part to lobbying efforts by companies such as Flos and Vitra, extended the copyright awarded to design objects from 25 to 70 years beyond the life of the designer. Naturally, the companies that called for the change are pleased. However, advocates of copying are increasingly speaking out, claiming that contrary to the ‘without ownership, there’s no incentive to innovate’ mantra of the manufacturers, increased protectionism not only puts a stranglehold on creative industries, but also actively stymies experimentation, creativity and innovation. Prior to a 2011 European Court of Justice ruling that sought to make copyright rules across the EU more consistent, intellectual property rights in each country for objects manufactured in quantities over 50 had typically been based on judgements about their utility: objects considered useful or functional were not usually awarded the same level of protection as ‘works of art’. While France has opted for more stringent protections, largely to protect its fashion industry, Italy, Germany and the UK take a more laissez-faire approach. ‘Historically, Italians were not protectionist about industrial design and in Germany everything was decided on aesthetic merits informed by a strong craft-based tradition,’ says Uma Suthersanen, professor of international intellectual property law at Queen Mary University, London. ‘But what the repeal of section 52 has done is remove from the courts this artificial demarcation between purposeless function and utilitarian function, which is somewhat worrying because judges will have to use aesthetic judgement, and those judgements can be very dubious.’ |

Words Crystal Bennes

Above: Paper replica of a sports car |

|

|

||

|

Gucci handbag made from paper |

||

|

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the confusion over aesthetics as a determining factor in rights protection provided a grey area that design manufacturers could exploit. ‘For example, a Nordic designer has said he is not manufacturing something that circulates in the general market,’ Suthersanen says. ‘He argues that he is creating something of beauty and so it shouldn’t fall under the rubric of design law but should be protected as an artistic work. That’s quite a spurious argument, but maybe it is time we acknowledged designers. Why shouldn’t their work be protected in the same way as art or music?’ She asserts, however, that the new protection for life plus 70 years is too long: ‘It’s anti-competitive.’ On the other hand, manufacturers believe longer terms of protection afford greater commercial success, which in turn allows companies to support designers. ‘Our profits are not outrageous,’ wrote Tony Ash, managing director of Vitra, in a Dezeen article last year, ‘and part of that profit goes to the designer or their heirs in the form of a royalty … Why should these designers [Ash names Jasper Morrison and Barber & Osgerby] bother working any more if their designs aren’t even going to be protected?’ |

||

|

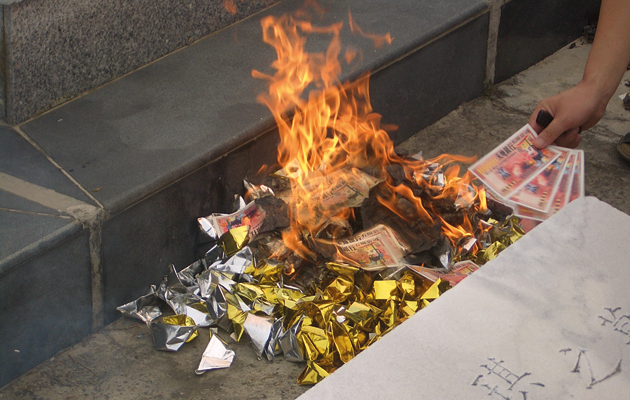

Fake money burned as part of a funeral ceremony |

||

|

Two things are problematic with this argument. The first is the existing royalties system, which has come under fire in recent years – criticised by everyone from curator Kieran Long to designer Inga Sempé, with a campaign at the 2011 Milan Furniture Fair held to raise awareness. The second is the implication that, before the extension of copyright protection to 70 years after the designer’s death, designers were not having work protected during their lifetimes. Companies such as Voga, legally producing copies of Arco lamps or DSW chairs, rarely replicate work of living designers such as Barber & Osgerby – the rules don’t allow them to do so until 25 years after the designers have died. Beyond the legal complications and lobbying power of the big brands, arguments against copying are often highly emotive, even manipulative. One need only look at the language used when intellectual property is under discussion: piracy, forgery, counterfeit. Such tactics also disregard important arguments for limiting the protection of intellectual property. Historically, copyright was awarded for 14 to 28 years, partly in recognition of the fact that ideas are not created in a vacuum. Inspiration is drawn from many sources, and new designs often build on the work of others – limiting the extent to which rights can be protected can address this. When corporate lobbying succeeds in extending copyright long after a designer’s death, this context is lost.

Charles and Ray Eames sit unaided by their DCM and Lounge chairs

The Eames DSW – probably the most copied chair in the world This one-sided focus on the economic argument obfuscates many important cultural, social and political considerations. Take the oft-repeated critique of China as the scourge of legitimate Western businesses, blamed by everyone from Tom Dixon to the late Zaha Hadid for replicating or just plain ripping off their work. ‘China is always branded the copyist,’ says Aric Chen, design and architecture curator at Hong Kong’s M+ museum, ‘but I think we need to be a bit more nuanced about it. China is the chief culprit in copying in part because it is where most of the manufacturing is done.’ One can’t help but wonder if Western anxiety over copying stems in part from concern about the loss of manufacturing industries. One could argue that innovation in design often results from incremental improvements, modifications or experiments in manufacturing processes. If those processes are no longer within easy reach, you may feel nervous about places where manufacturing capabilities are booming and turn to legal action. ‘The anxiety makes some sense, but I wonder how strategic it is to put so much effort towards lawyers when other efforts might be more fruitful in the long run,’ Chen says. ‘It isn’t a fair comparison, but you only have to look at how successful fashion companies have been focusing on international marketing and retail development rather than legal prosecution.’ |

||

|

Above and below: The V&A’s A World of Fragile Parts exhibition at this year’s Venice Biennale |

||

|

Chen also cites the much-discussed phenomenon of Shanzhai, mobile phone ‘improvements’ made in Shenzhen, the global hub of electronics manufacturing. ‘They started out knocking off Nokia or Apple phones, but then adding features like dual SIM cards,’ Chen says. ‘Then, things evolved and some manufacturers started making phones with over-sized buttons for the elderly. None of the big companies had thought to create anything like that.’ In recognition of the important role of the copy in Asian design culture, M+ will be showcasing innovative copies from the region – including the Shanzhai phones – in its first major design exhibition this November. Also appearing in the exhibition will be Copy-tiam by Singaporean designer Hans Tan. This 2012 project makes freely available detailed blueprints of the kopitiam chair, famously associated with Singaporean coffee-house culture. Although not an exact copy, the kopitiam chair has its roots in Thonet’s No. 14 chair. ‘It’s fascinating how this chair has become understood as a piece of national identity, but it’s basically a copy of the Thonet chair,’ Chen says. ‘Singaporean society claimed a kind of ownership of this chair, but now Hans has made it open source.’ |

||

|

||

|

This kind of sharing and disseminating of ideas is already taken for granted by designers and architects, but the role of the digital technology that enables it is complicated. On the one hand, the internet is a source of inspiration; on the other, one wonders whether copying would even be a cause for complaint without the ability to easily discover that it’s happening. Emerging digital technologies are, however, also providing copying with a new, unexpected status: that of saviour. Widely acclaimed at this year’s Venice Architecture Biennale, the Victoria and Albert Museum’s exhibition A World of Fragile Parts examines the role of the copy in cultural preservation and dissemination. From decorative reconstructions of 18th-century porcelain fountains to 3D-printed models of bomb clouds used by human rights agencies to compile reports in conflict zones, the exhibition highlights a cultural understanding of the copy as more than mere plagiarism. ‘I feel a mandate to lift the stigma off the copy and show it for what it is – a vast field of inquiry, some of which is negative, but a lot of which is positive,’ says curator Brendan Cormier of the V&A. ‘Perhaps the idea of the copy as a tool for cultural preservation is an easy pill to swallow, but it was important to convey the idea that the production of copies is not about preservation, but about perpetuation – about how the copy provides the ability for changes and modifications of culture over time.’ |

||