|

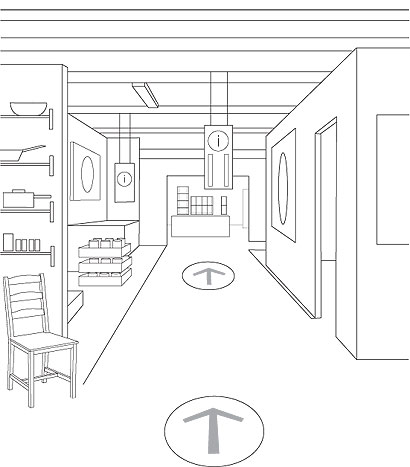

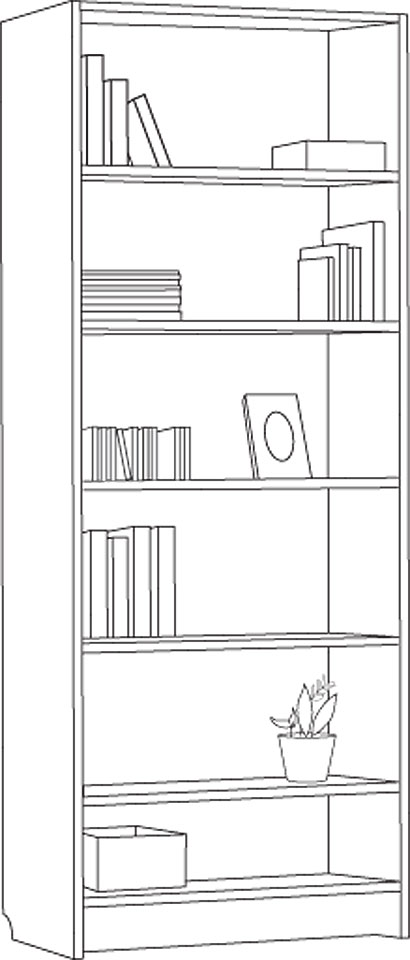

Everyone knows what an Ikea store is like, but how is the flatpack furniture that fills our homes in ever growing numbers actually designed and made? We visited Ikea’s birthplace in southern Sweden, and a factory that makes a famous bookcase, to find out Stealing Beauty (2007), is a short film by Israeli artist Guy Ben-Ner, starring Ben-Ner, his wife and their two children, that he filmed in Ikea stores, without permission, in three different countries. From the moment Ben-Ner steps on to a blond bedroom-set, briefcase in hand, and calls out, “Hi, honey, I’m home,” the most obvious part of his joke is clear. Nothing could be less private than faked rooms in the world’s most ubiquitous furniture store, but then how private are our homes – and how individual are we – if we surround ourselves with exactly the same stuff? Dave Seger’s Ikea Heights (2009) takes a slapstick approach to the theme as he and his friends film a melodrama in his local store in Burbank, California, dodging the intervention of real customers and security guards. These films (and others – it’s a growth genre) play on our familiarity with the stores, and our shared unease about them, so I wasn’t at all surprised when I went to an Ikea store for the very first time last month, and felt right at home – the homes of everyone I know. The store I visited is in Älmhult in southern Sweden. It’s the small town where Ingvar Kamprad, the 86-year-old founder of Ikea, was born, and it’s where he opened his first store in 1953. In Älmhult Ikea is really a town within a town. As well as the 24,000sq m store (originally built as 6,000sq m), there’s a museum, and an Ikea hotel meant mainly for staff visiting from all over the world – for Älmhult is also the home of Ikea Sweden, the national, and still most important, division. Juni Wannberg, who now works in the information department but started as a product developer at the company 28 years ago, told me as we toured the museum: “The heart of Ikea is here. It’s still the only place in the world where we have the full cycle of product development, from the first idea in the head of a product developer to a designer giving it shape, to the pattern shop making a prototype, to it being produced, going into a store and into the catalogue.” One wall of the museum is covered in statistics: 208 million copies of the catalogue were produced last year; there were an estimated 734 million visits to the stores. Here are some more: in the financial year ending September 2011, Ikea made a net profit of €2.97 billion on worldwide sales of €24.7 billion – and there are over 300 stores worldwide (but none in South America or Africa). This growth is all the more remarkable considering that the second Ikea store, in Oslo, opened only in 1963. Much of this growth has been in the last decade and, looking at the Billy bookcase, one of Ikea’s bestselling items, tells us what the growth means for manufacturers. In 2011, reports of the death of Billy were greatly exaggerated. The Economist reported that the bookcase with five adjustable shelves was undergoing changes: a deepening of the shelves from 11 inches to 15, and the introduction of glass doors meant it was no longer for books, but a display case. From here it was a quick step to the death of the book itself. It was a fuss about nothing; the new model was an addition to the range, not a replacement. But it focused attention on an item that Ikea has had in production since it was designed by Gillis Lundgren in 1979; an item so important to the company that in 2009, on its 30th anniversary, it published a book celebrating Billy. Over 45 million copies of the Billy bookcase have now been sold, and many have been made by a family firm called Gyllensvaans, which is based a couple of hours’ drive north from Älmhult in the village of Kättilstorp. Run by the siblings Mats, Eric and Karin Gyllensvaan, who took over from their father, who founded the company in 1946, Gyllensvaans delivered their first furniture to Ikea in 1952. Eric and Mats took me round the 60,000sq m shed where the bookcase is produced. Eric explained 40,000 sq m of the new area has been added in the last seven years, adding that when they built the first factory on this site, they had thought that “a thousand square metres was huge – we said, now it’s enough forever.” Every day Gyllensvaans receives 24 truck deliveries of chipboard (mainly from Sweden and Norway, with a small amount from Germany), and produces roughly 100,000 flat pack packages of the bookcase every week. Billy is probably the least changed of all the items in the Ikea range, but the fourfold increase in its production – from 300,000 units a year in 1999, to 1.2 million now, has prompted Gyllensvaans to move to full automation and, two years ago, to 24-hour-manufacturing. The firm employs just over 200 staff – only double the number it did in 1988, when it made 200,000 bookcases a year – which tells you how much more efficient it is. The constant push for increased efficiency is central to how Ikea works, and what it demands of its suppliers: ever lower margins. Gyllensvaans is a first-tier supplier – which is to say that it puts together a full flat-pack item, ready for delivery to stores and distribution centres (of which there are nearly 40 worldwide). The price of the bookcase in the Swedish catalogue is the same today as it was in 1988 – “So you can imagine how much less we have,” Eric Gyllensvaan said. He was smiling, but huge amounts of investment are required to provide such increased volumes – €20 million for the assembly lines and machinery that’s currently in operation.

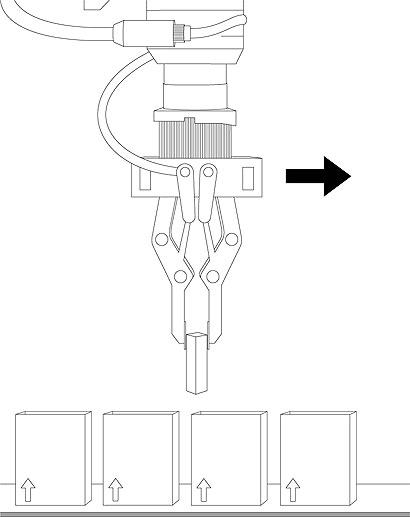

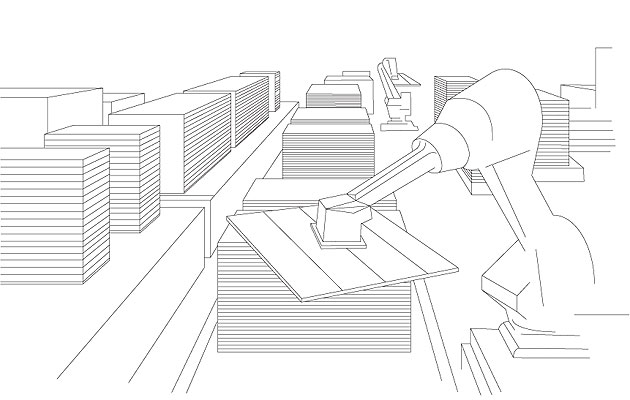

We moved up stairs and along walkways – small streets, really – looking down on the conveyor lines which take in chipboard and cut it into sections for backs, sides and shelves. The cut pieces are then glued and sealed with edge bands before being drilled for holes, and packed. Eric, a man who doesn’t take himself at all seriously, said, “We have to walk out quickly, because if you see too much, you’ll see how easy it is.” It doesn’t look that easy at all: though calm, the factory is loud and in constant motion – forklift trucks move at intervals almost as regular as the robotic arms and conveyor belts, to deliver chipboard to the start of the process or pick up the finished packages. The packing arms are the real stars of the show. Earlier at Älmhult, they had been described to me as a piece of “Moonbase Alpha”. It’s no exaggeration to call them mesmerising. The line of some 20 Motoman robots pack four packages in parallel, in a system designed by Eric and Mats themselves. The brothers started working in the family firm almost straight out of school. Earlier, in Älmhult, Börje Lindgren, the Ikea product developer with whom the brothers work most closely, told me that Eric and Mats are not just owners and entrepreneurs, but also very good technicians. When I asked the brothers about this, Mats said: “We grew up working here,” and Eric chipped in, “At the start, we had no maintenance department, we made all the repairs ourselves.” Mats said, “Before we could have gone out and started every machine … now it’s everything with computers.” Although production methods have changed, Ikea’s way of working with designers, and the way those designers work with factories, has stayed the same. The company has an in-house team of 10-13 designers, and employs hundreds more on a freelance basis – and all design decisions are taken in Sweden. Ikea designers are kept busy by the fact that 20 percent of the range drops out every year (some of it returns later, of course, depending on prevailing fashions). Knut and Marianne Hagberg, a Danish brother and sister team, have worked for Ikea for 33 years. They can be working on up to as many as 20 new products at a time, at very different stages of development. Their designs in plastic and metal have won them many awards, but they’re clear that it takes a certain kind of personality to be an Ikea designer. The process begins when a product developer approaches them with an idea for a new line. Knut takes the example of Elmer, a stackable chair designed for restaurant use, with a tubular chrome frame with a polycarbonate plastic seat wrapped round it. They were told it was for use in Ikea restaurants, needed a minimum of screws and had to weigh about 4 kilos. Knut and Marianne describe the process as “a designer’s dream” because the Ikea pattern shop is able to fabricate almost any drawing they take to it. (The Hagbergs jokingly calls themselves “dinosaurs” for still drawing at every stage.) Unlike most designers, they have to consider the demands of flat-packing from the very beginning, and that means understanding how potential factory suppliers work. Marianne said, “Normally Knut and I will go to visit the supplier to see the facilities and to see how we can fit it to their production.” Since the Hagbergs live in Lund, about an hour away on the train towards Copenhagen, they visit the Älmhult store every day. Marianne said, “We normally take a tour and see how the customer meets the product. That’s the most important thing … Sometimes you hear a lot of strange things, like ‘Oh, it’s nice, but I don’t know how to use it,’ or ‘I’ll buy two or three.'” Some of the walls of the headquarters in Ikea Sweden are covered in large English slogans, from a 1976 document by Ingvar Kamprad called “Testament of a Furniture Dealer” – a terse, nine-point guide to modern, mass production. Point 3 says: “Profit gives us resources.” What seems clear from having the Ikea system explained to me (students of mass production requiring lots of capital will already have worked this out) is that Ikea has no choice but to keep on expanding and selling even more of its products to maintain current prices. This will require greater investment and more change on the factory floor. And it seems likely that more of its manufacturing will move outside Europe. But back in Kättilstorp, Mats and Eric are preparing themselves, not immediately, but eventually, for when they’ll have to make more products so that they can make more deliveries to stores, bypassing distribution centres. (Currently, there are no stores that can take a truck delivering only Billies.) In Älmhult, I got used to rounding corners and coming across Ingvar Kamprad’s final point: “Most things still remain to be done. A glorious future!” On this basis, Ikea will be furnishing even more of the world and even more of us will inhabit its ready-made film sets.

|

Image The Lindström Effect

Words Fatema Ahmed |

|

|

||

|

|

||