Commissioned by Audemars Piguet Contemporary, Center for the Critical Appreciation of Antiquity is the artist’s largest and most ambitious artwork to date

Words by Harriet Thorpe

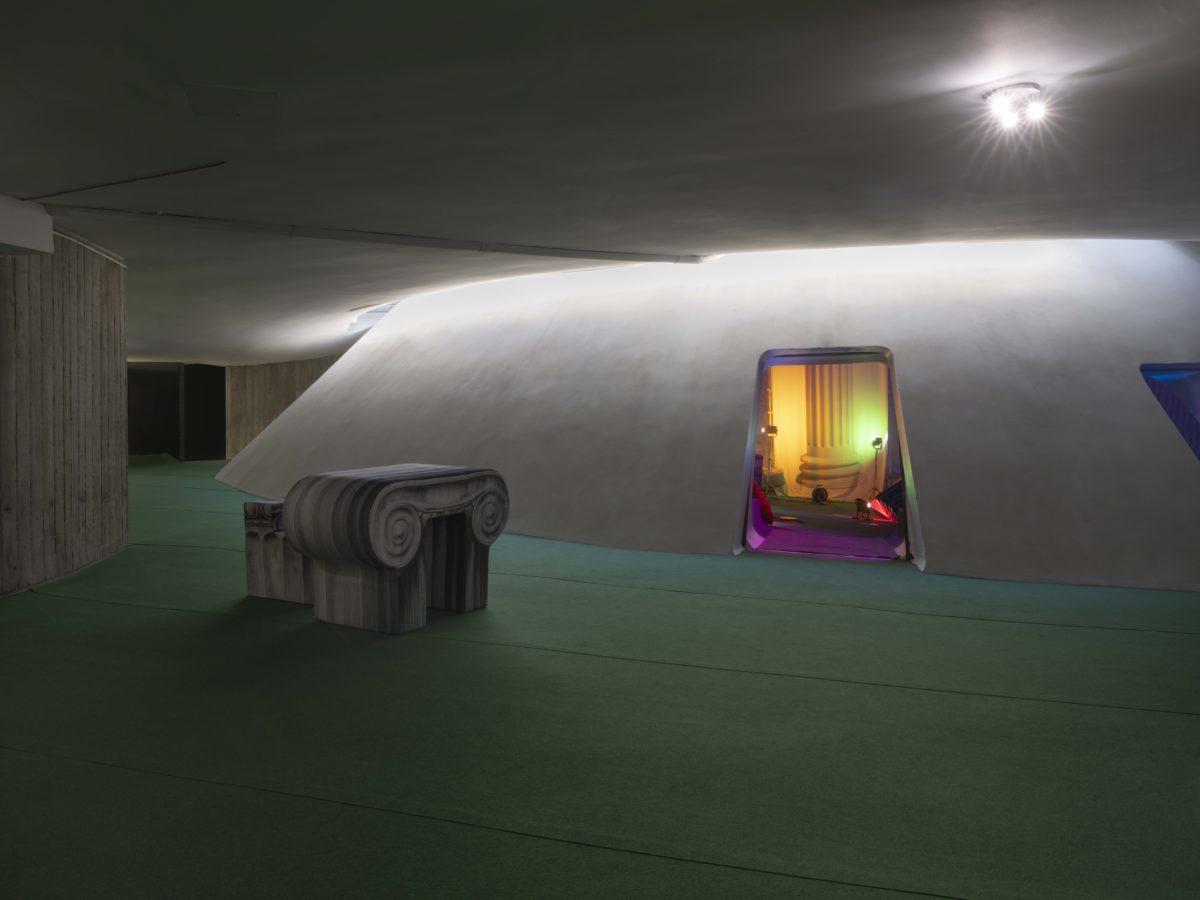

This month in Paris, the Espace Niemeyer – the gallery space in the auditorium of the former French Communist Party Headquarters designed by Brazilian architect Oscar Niemeyer and completed in 1980 – plays host to the Center for the Critical Appreciation of Antiquity, an installation by Athens-based Greek artist Andreas Angelidakis.

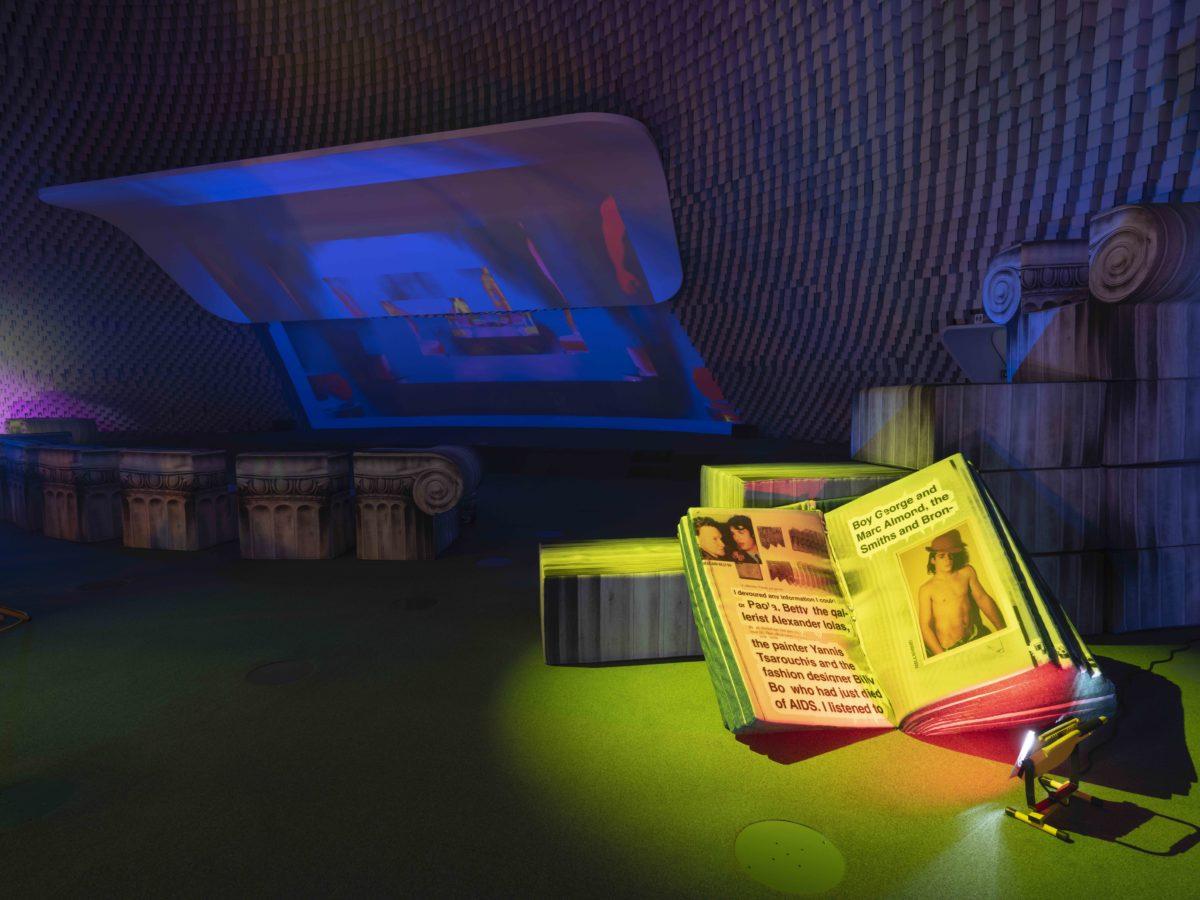

The sunken auditorium dome with its bright green carpet, has been transformed into a radical construction site of references traversing archaeology, architecture, queer club culture, and social media amongst other themes; and it’s been loaded with the artist’s trademark ‘soft ruins’, foam furniture that seeks to encourage play, relaxation and discussion. ‘It’s Disney meets UNESCO,’ says Angelidakis.

Describing himself as an ‘architect who doesn’t build’ (he studied architecture at the Southern California Institute and Columbia University), Angelidakis’ work explores both the physical and non-physical architectures of urban culture. Since childhood, he has been fascinated by Athens’ ruins, which he would ritually attend with Norwegian relatives of his mother when they visited.

While tourists experience ruins in Athens as the purest form of history, this installation explores the subjective nature of ruins – ancient and contemporary – as subject to the practice of archeology which Angelidakis calls ‘story-telling dressed up as science.’

His art practice digs into how international politics and economies are embedded in Athens’ architecture from antiquity, to modernity, to today: ‘The archaeology schools that excavated Greece were not Greek, they were French, German and British. The French were the first school of archaeology to establish an excavation. So the ancient history of Athens is very much linked to these three countries.’ Therefore, he asks visitors to question exactly what has been chosen to be conserved, reconstructed or appropriated elsewhere, by whom and for what purpose?

One storied ruin has always intrigued him in particular – the Greek Temple of Olympian Zeus, which plays a central role as a soaring and disruptive column in the installation. The largest temple of the ancient world, its construction dates back to 6th century AD. It was finally completed by Roman emperor Hadrian in the 2nd century AD – though less than a century later it was damaged and then after forever at peril to ever-encroaching adaptation.

It is in the undocumented and rumoured adaptations of the temple and other ruins in Athens where Angelidakis dwells – he queries whether a more ‘critical’ archaeology would have preserved a mosque in the Parthenon, or the unofficial habitation of a Stylite monk atop a column.

Angelidakis finds that the erased histories of antiquity and contemporary society are often no longer physical – traces might only be accessible in drawing scans buried in internet blogs, in ephemeral cultures hidden behind the facades of closed-down night clubs, or even forever buried in deleted CCTV footage. The installation gathers together his own personal archaeology – of obsessions, experiences and insights – showing that multiple cities can exist in parallel, it all depends to which city you subscribe.

Referencing the social and political intentions of radical Italian design of the 70s, including the furniture of Gufram and Sottsass for example, his ‘soft ruins’ take the form of ‘books published as chairs’, offering a place to rest with a story to tell. The books hold photographic documentation of subcultures, copy-righted cultural documents, and censored social media investigations. To the artist, ruins are never hard facts, they are always malleable and blurry, and require critical thinking.

So how exactly should we be critical today of contemporary Athens? A yellow construction rubbish chute spirals down from the top of the precarious central column, referencing Athens’ contemporary construction scene driven by Airbnb. ‘The boom of Airbnb in Athens was in 2017,’ says Angelidakis.

‘The city was finding a new order of architecture, and it was Airbnb. As a place, it changes every 10 years, with every kind of immigration crisis, political crisis or financial crisis. Athens is always between the Ottoman Empire and a contemporary city, and the two identities are conflicting. It is a city that is never really resolved. Paris is fixed because it’s resolved, it understands its identity.’

In Paris, the Espace Niemeyer could perhaps be seen as a symbol of this; a preserved piece of 20th century architecture, protected and present to tell its tale and functioning as an office building and gallery space allowing people to visit when fashion shows and exhibitions are hosted.

Denis Pernet, curator at Audemars Piguet Contemporary which commissioned this work from Angelidakis, suggested the space as a location and worked closely with him to bring his ideas to life. Without a permanent gallery location Audemars Piguet Contemporary – which celebrates its 10th anniversary this year – commissions new works from artists at new scales and formats that crop up in interesting places such as the High Line in New York or 180 The Strand in London.

For Pernet and Angelidakis, the Espace Niemeyer felt apt for this installation, conjuring ideas around heritage, democracy, futurism and science fiction. ‘I see Niemeyer as someone who had a vision for a life that didn’t come to fruition – he was proposing a future that never happened. What I’m suggesting is a past that was otherwise,’ says Angelidakis.

Center for Critical Appreciation of Antiquity, commissioned by Audemars Piguet Contemporary, is on view at the Espace Niemeyer in Paris from 11-30 October, 2022

Photography by Julien Gremaud