|

Gio Ponti (image: Gio Ponti Archives) |

||

|

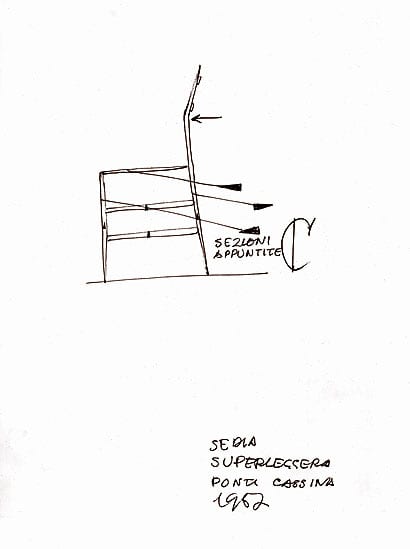

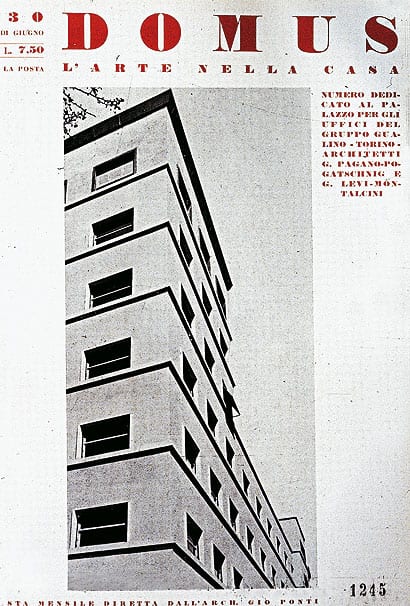

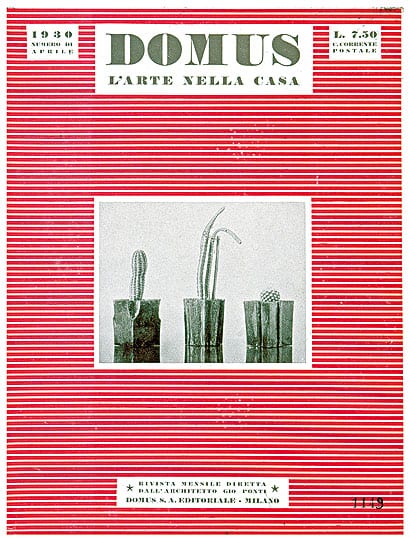

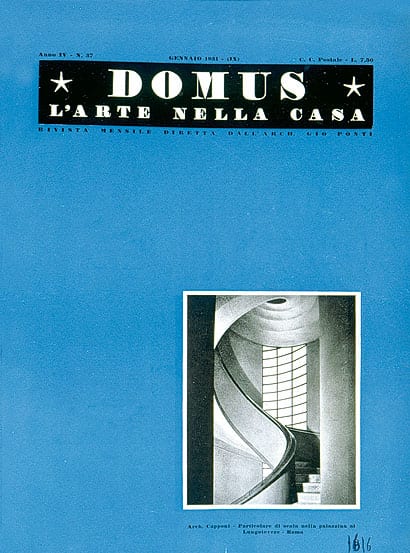

Gio Ponti is the subject of a new retrospective at the MAXXI in Rome, running until 13 April 2020. Here, in a piece from the archive, Justin McGuirk explores Ponti’s influence on the anniversary of his death. Gio Ponti deserves to be remembered for many reasons but above all as a peculiarly Italian phenomenon. He was one of what we could call the “maestri” – a succession of architects who dominated Italian design from the post-war era until relatively recently. As well as erecting buildings and filling them with their products, they founded movements and magazines. Among their number are Ettore Sottsass, Alessandro Mendini, Vico Magistretti and Andrea Branzi. Ponti, who died in 1979, 30 years ago this month, prefigured these modern renaissance men. When people think of Ponti, they will no doubt recall one of three things: the featherweight Superleggera chair, which he designed for Cassina in 1957, the 1958 Pirelli Tower, that remarkable cigarette case of a building that remains Milan’s signature modern landmark, and Domus, the magazine he founded in 1928. Of those, Domus deserves particular scrutiny because it was the organ through which so many architect-designers controlled the discourse of Italian design. It is something of an Italian tradition to be both architect and “direttore” of a magazine – it would never happen in the UK, where journalism remains a defiantly independent trade. In Italy, however, architects are taken seriously as cultural figures, and Ponti was one of the most assiduous. He was an editor for 50 years, mostly at Domus – except for six years in the 1940s when he went off to found a magazine called Stile – which he steered right up to his final years. Ponti loaded Domus with his enthusiasm for modern design, so that it became a portal onto an Italian world of modern elegance – La Dolce Vita. The writer Joseph Rykwert worked at Domus in the 1960s and 1970s under Ponti’s tenure and remembers a man with “an ability to be entertained by almost anything”. “Every morning, before anyone else was around,” recalls Rykwert, “he would go down to his office and write letters. Mostly they were drawings with words, which he would send to his friends or the Pope or the president of Italy. They were expressions of affection.” Born in 1891, Ponti launched his career in the 1920s in industrial design rather than architecture, as the art director of ceramics company Richard Ginori. His output thereafter is awkwardly diverse from the historian’s perspective. It ranged from the Brancusi-esque sculpting of La Pavoni espresso machine (1948) to the rustic simplicity of the Superleggera chair to the op-art styling of the interior of the Villa Arreaza in Caracas. Architecturally, it is difficult to reconcile the modern Pirelli tower with the postmodern, castle-like crenellations of the Denver Art Museum (1971). But that was Ponti, even as an old man moving with the times. As the maestri pass away (most recently Sottsass and Magistretti), it seems possible that the phenomenon is also dying out, as there are few obvious successors. This is probably for the best. The Italian design world has been a gerontocracy for too long, presided over by venerated white-haired geniuses. Youth-obsessed northern Europe has long been bemused by Italy’s lack of prominent young designers. Even as the young turks of Radical Design in the 1970s, Sottsass and Mendini were no spring chickens – Sottsass was nearly 60.

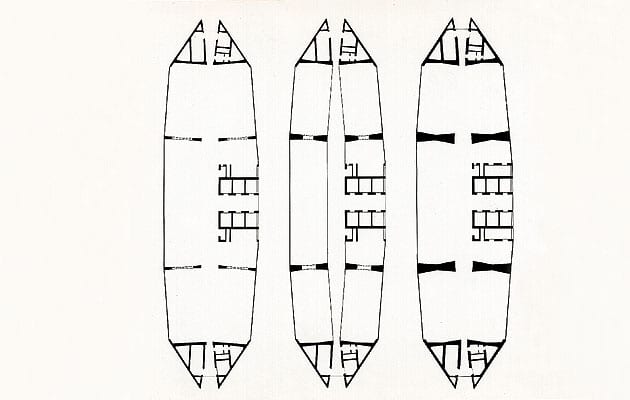

Ponti’s drawings of his Superleggera chair (image: Gio Ponti Archives)

Issues of Domus magazine from the 1930s (image: Gio Ponti Archives)

Issues of Domus magazine from the 1930s (image: Gio Ponti Archives)

Issues of Domus magazine from the 1930s (image: Gio Ponti Archives) |

Words Justin McGuirk |

|

|

||

|

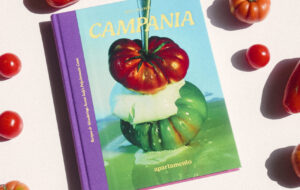

Plans of the Pirelli Tower (image: Gio Ponti Archives) |

||