Designing everything from electricity pylons to circular dresses, the husband and wife duo individually and together played a big part in Finnish design history. Now a new exhibition at Design Museum Helsinki is showing their work to a new generation

Photography courtesy of Antti Nurmesniemi’s archive featuring Antti and Vuokko Nurmesniemi, 1980s

Photography courtesy of Antti Nurmesniemi’s archive featuring Antti and Vuokko Nurmesniemi, 1980s

Words by Dominic Lutyens

Finnish designers husband and wife Antti and Vuokko Nurmesniemi are celebrated in their native country yet are relatively unknown outside it.

From the 1950s to the 1980s in particular, this multi-talented, forward-thinking, socially progressive couple were feted in Finland, much as fellow Finns Alvar and Aino Aalto and Americans Charles and Ray Eames were.

Antti (1927-2003) and Vuokko, born in 1930, sometimes collaborated but mainly pursued independent careers. Antti created interiors and furniture for the modernist Palace Hotel in Helsinki in the 1950s, co-designed carriages in ultra-pop tangerine for the Helsinki Metro with Börje Rajalin from 1968 to 1977 and founded his interior design studio in 1956.

Vuokko worked for Marimekko from 1953 to 1960. In 1964, she founded her own fashion label, Vuokko, which still has a shop on Korkeavuorenkatu Street in Helsinki. Her niece, Mere Eskolin, has been its managing director since 2019.

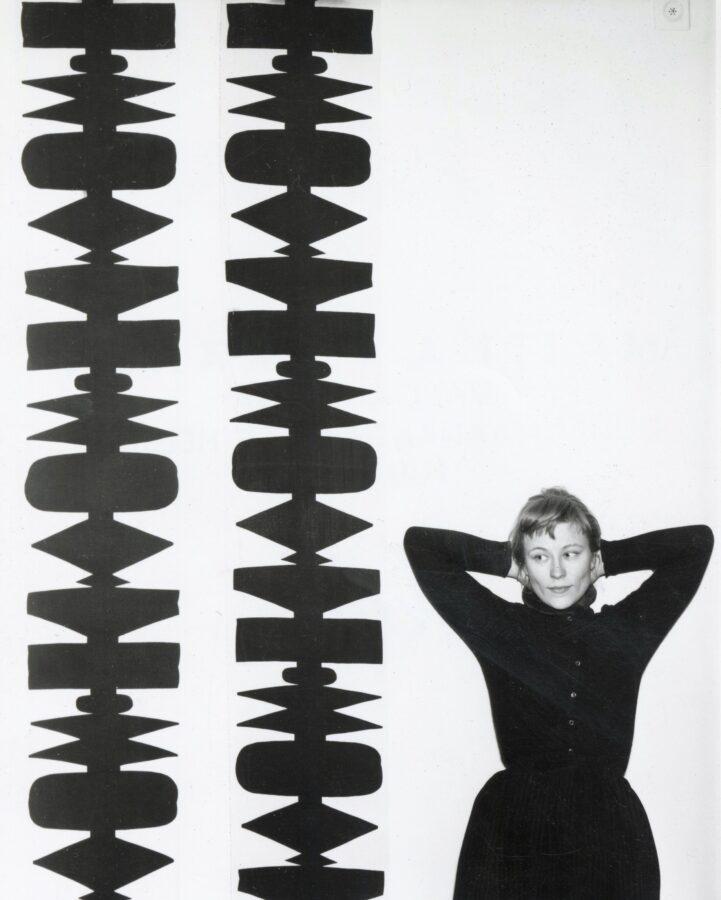

Photography courtesy of Antti Nurmesniemi’s archive featuring Vuokko Nurmesniemi and fabric Kakemono, 1957

Photography courtesy of Antti Nurmesniemi’s archive featuring Vuokko Nurmesniemi and fabric Kakemono, 1957

Now the couple are the focus of an exhibition called Antti + Vuokko Nurmesniemi at Design Museum Helsinki, which runs until 9 April 2023. Nearly all of Vuokko’s clothing on display is drawn from the museum’s collection of over 1,000 of her designs. ‘This is the first time Antti and Vuokko’s work has been shown together,’ says co-curator Susanna Aaltonen.

‘Their work from the 1950s to the 2000s forms a big part of Finnish design history and modernism and is still relevant. Antti created interiors and furniture for over 50 years and designed everything from coffee pots to electric pylons. The Helsinki metro trains are still a major symbol of the city.’

‘Although they mostly worked independently, Vuokko said Antti was the most important person in her life, while Antti saw Vuokko as a wife, friend and colleague,’ continues Aaltonen. ‘Vuokko designed fabrics that covered Antti’s furniture and Antti interiors and graphics for Vuokko’s boutiques, which also sold his furniture.’

The exhibition includes images of their modernist Helsinki home, designed by Antti and completed in 1975. The high-cheekboned Vuokko and bespectacled, professorial-looking Antti were photographed in its sleek interior, frequently used for shoots to publicise new furniture and fashion collections.

Photography by Sameli Rantanen / Asun featuring living room furniture, Antti Nurmesniemi: Chairs 004, 1980, Vuokko Oy; Lamp, 1957, Artek; Sofa, 1968, Vilka Oy. Cushions, Vuokko Nurmesniemi, 1975–1980, Vuokko Oy

Photography by Sameli Rantanen / Asun featuring living room furniture, Antti Nurmesniemi: Chairs 004, 1980, Vuokko Oy; Lamp, 1957, Artek; Sofa, 1968, Vilka Oy. Cushions, Vuokko Nurmesniemi, 1975–1980, Vuokko Oy

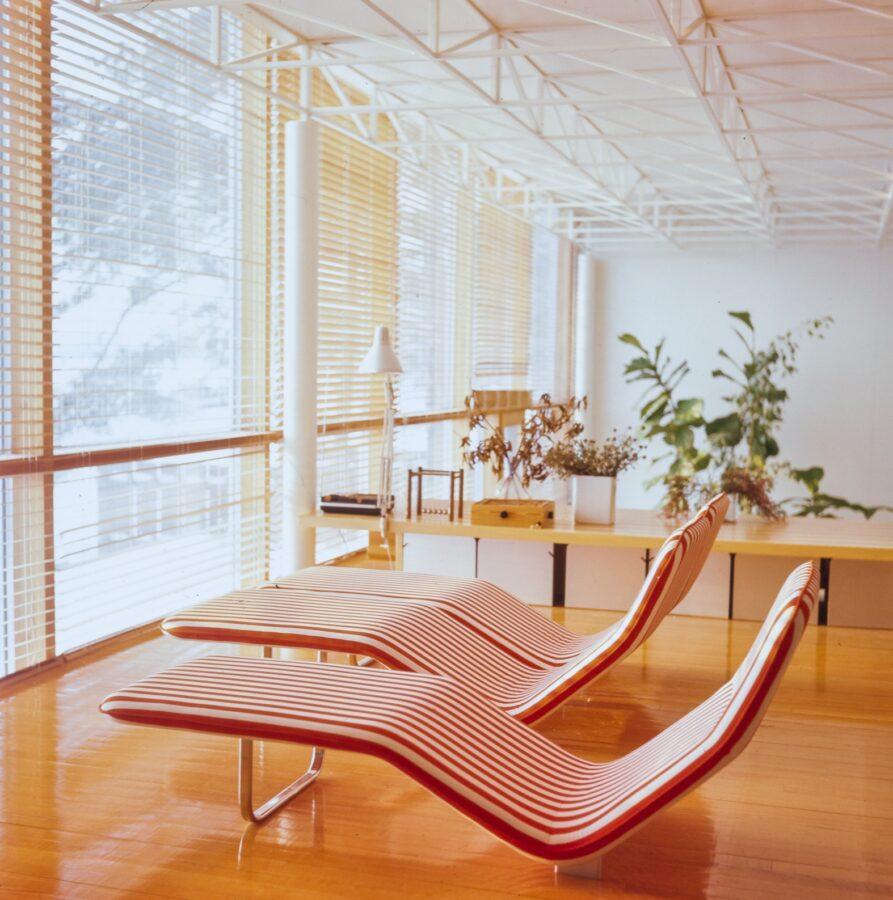

‘The house was a place for their private life and to meet colleagues and showcase modern Finnish design,’ says Aaltonen. Several key Antti designs have recently been reissued. Available through the Vuokko label’s website, these will bring more attention to the Nurmesniemis’ legacy. They include his Sauna stool, 004 chair, upholstered in a black-and-white or red-and-white stripe fabric designed by Vuokko, Amer lounge chair and Pehtoori coffee pot.

Vuokko Eskolin-Nurmesniemi, as she is also known, is more likely to be on the radar of design buffs worldwide than Antti. She studied ceramics at the Institute of Industrial Arts in Helsinki, graduating in 1952, and designed ceramics and glassware for Finnish tableware company Arabia from 1952 to 1953.

But she made her mark as an influential textile designer at Marimekko. Armi Ratia, who co-founded it in 1951, hired Vuokko in 1953, the year she married Antti. Early on, Ratia asked Vuokko to copy a mosaic-motif print. The result, a striped pattern called Tibett, bore no resemblance to a mosaic but its boldness impressed Ratia.

Timid, itsy-bitsy florals were the norm then in the textile world but Ratia counterintuitively championed simple stripes or outsized, abstract motifs in offbeat colour combinations. Soon after, Vuokko created Marimekko’s iconic, pinstripe-like Piccolo print used on another of her designs – the utilitarian Jokapoika shirt.

Photography by Paavo Lehtonen featuring Vuokko Nurmesniemi, dress Myllynkivi 1967, pattern Pyörre 1964. Photos are taken at Nurmesniemi’s studio home in Kulosaari 2022

Photography by Paavo Lehtonen featuring Vuokko Nurmesniemi, dress Myllynkivi 1967, pattern Pyörre 1964. Photos are taken at Nurmesniemi’s studio home in Kulosaari 2022

Based on Finnish farmers’ shirts, this was a man’s garment but was co-opted as womenswear as a loose-fitting shirtdress, a comfortable alternative to the constricting, wasp-waisted silhouette of the 1950s. Ratia astutely promoted Marimekko worldwide, particularly in the US. In 1954, the label participated in the exhibition Design in Scandinavia, which toured America.

In 1959, Harvard University professor Benjamin Thompson stocked the label’s roomy dresses at his avant-garde Design Research store in Cambridge, Massachusetts, established in 1953. Jackie Kennedy snapped up eight frocks. Another American fan of the label, artist Georgia O’Keeffe, owned a Piccolo-print shirtdress with aubergine and lilac stripes.

Vuokko took a sculptural approach to fashion with her own label. In the 1960s, she designed her experimental, circular dress called Myllynkivi. ‘Vuokko identifies more as a designer than a fashion designer,’ says Eskolin. ‘Issey Miyake greatly admired her designs.’

According to Eskolin, Vuokko, who was appalled by oil spills in the Baltic Sea, was ahead of her time for taking an ecological approach: ‘She refused to waste fabric, ensuring offcuts were recycled.’

Photography by Antti Nurmesniemi featuring Antti Nurmesniemi, chaise longue 001, Vuokko Oy, at Nurmesniemi’s studio home in Kulosaari

Photography by Antti Nurmesniemi featuring Antti Nurmesniemi, chaise longue 001, Vuokko Oy, at Nurmesniemi’s studio home in Kulosaari

Finland was geographically and culturally isolated after the Second World War, but the inquisitive pair travelled abroad extensively, despite the dangers and high costs involved: ‘Travel from Finland was expensive after the Second World War when people had little money,’ says Eskolin. ‘

There were fewer plane and boat connections. Travelling by boat was perilous as there were mines in the Baltic. But Vuokko and Antti travelled often, including to India after he won the Lunning Prize [a US gong awarded to Scandinavian designers] in 1959. They were well- connected and friends of Charles and Ray Eames.’

While this revolutionary designer couple may not be widely recognised outside Finland, this show will spotlight their achievements and should help to raise their profile worldwide.

Read more in ICON 210: The Finland Issue or get a curated collection of architecture and design news like this in your inbox by signing up to our ICON Weekly newsletter