It was the car that drove Italy’s economic miracle, swerving past the Vespa to become Italians’ favourite ride – but it never escaped the sense that its designers were having a bit of a laugh, says Brendan Cormier

Words by Brendan Cormier

Think of a ‘people’s car’, and your mind might turn to Volkswagen (the name literally means that, after all), the Nazi-led project to build an affordable car in 1930s Germany. Or maybe the Citroen 2CV, designed by polling thousands of French citizens about what they wanted out of a car (a boot large enough to fit a whole live pig, apparently). Add to this list the Morris Minor, the Mini, the Trabant, the Lada, and some unifying characteristics start to emerge: there’s an obvious economy to this group, both in their shape and price tag. But there is also a more elusive quality: they are all somehow ‘fun’.

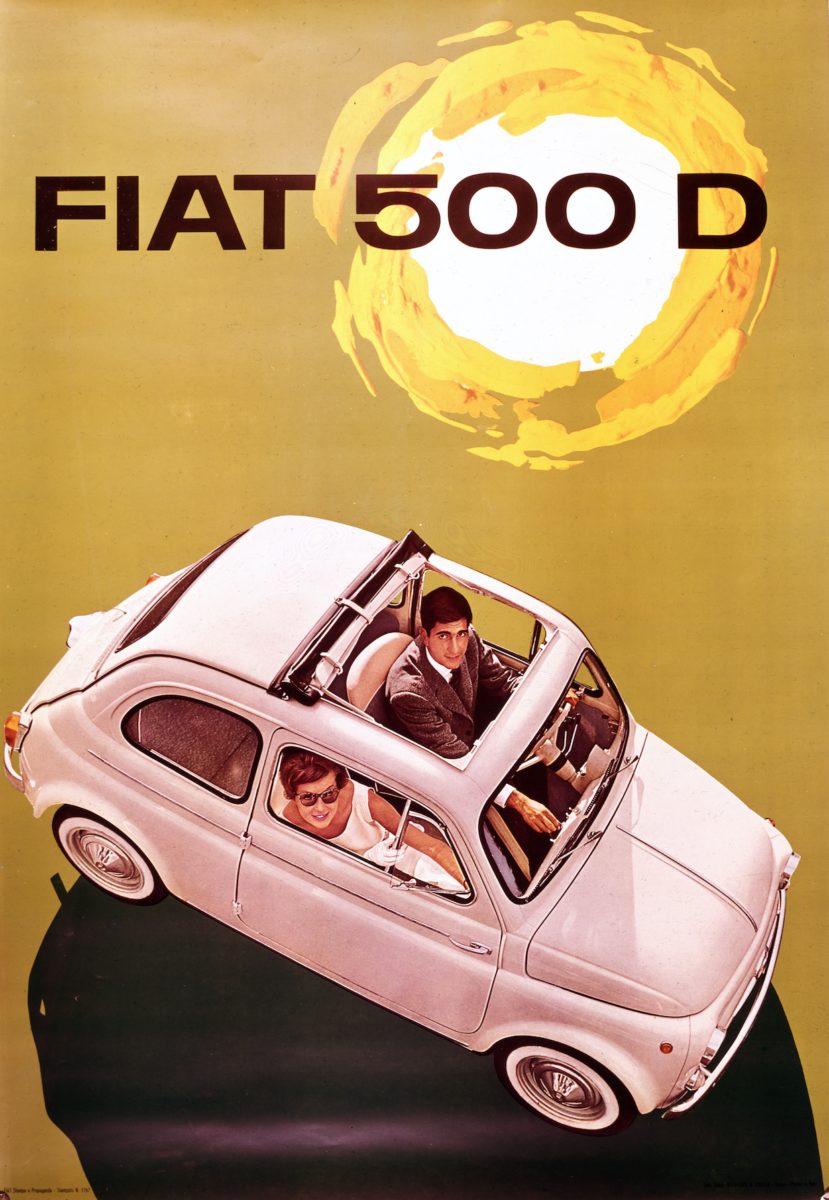

The most fun and also funniest of them all is the Fiat Nuova Cinquecento. It’s not slapstick funny – like the bumbling Italian-accented Luigi in the Cars movie franchise, who dons the avatar of a Cinquecento – but a more knowing kind of funny: as if after 50 years of global car production, there were enough designs out there to start having a bit of a laugh. The most impressive thing about it, however, is that after first rolling off the line in 1957 with all its jocular flare, it would go on to help permanently change the landscape of modern Italy.

The dream of a people’s car came to Europe surprisingly late. Stateside, Henry Ford had unlocked the secret to cheap mass production as early as 1908, with the introduction of his bare-bones no-nonsense Model T. Being the first truly affordable car for the middle and working classes, it soon dominated the field, becoming the de facto car of the people wherever it was sold. European car companies were transfixed by the Americans’ success, and making a pilgrimage to Detroit to witness first-hand Ford’s factories became a must for any ambitious car entrepreneur.

Giovanni Agnelli, who founded Fiat Car Manufacturing in 1899, made multiple trips to Ford to see if the moving assembly line miracle of the Midwest could be translated to his factories in the foothills of Piedmont. Inspired by what he saw, he hired the architect Matté Trucco to build him a modern new production facility on the outskirts of Turin. In 1916, construction began on the fabled Lingotto site – a poetic yet impractical translation of Ford’s assembly line into a veritable architectural machine: parts would enter at ground level, gradually get assembled as they moved up and through, and emerged on the roof as fully made cars ready to be driven around a rooftop racetrack before heading down into city streets.

Lingotto was where Agnelli’s first attempt at a people’s car was realised: the Fiat 500 Topolino. Designed by engineer Dante Giacosa and launched in 1936, it was lauded for its unique look and diminutive shape, and provided a relative success for the company. But the interruption of the Second World War marred the car’s sales. Meanwhile, the Lingotto production facility was proving to be more an elegant architectural folly than a factory capable of producing at the scale of Fiat’s American competitors.

Undaunted, the company relaunched its bid for an affordable people’s car in the early 1950s. During that period, sales of small motor-scooters such as the Vespa were sky-rocketing and Fiat was keen to produce an affordable alternative. Giacosa was tasked with stripping down a car design to its barest essentials. The Nuova Cinquecento was deliberately made bulbous and round to avoid the use of excess metal. It had a large hole cut out of the top for similar reasons – given a fabric top and cleverly rebranded as a sun roof.

Giacosa also took a cue from Volkswagen and moved his engine to the back, which allowed for more interior space. When it debuted at the Turin Motor Show in 1957, it was not an immediate hit. The motor was too small and the amenities too few to attract a wide demographic. The company pivoted by offering slight variations in its models, more options, and more horsepower.

The strategy worked and sales gradually rose – in 1957, only 12,000 were sold, by 1962, 108,000, and in 1970 sales reached a high of 351,000. In fact, 1970 was the peak year of production for Fiat’s Italian operations across the board, with 1.4 million cars produced by a labour force of 100,000. The Cinquecento had been key to unlocking Giovanni Agnelli’s dream of harnessing mass production to reach figures unheard of in Italy.

As for the users of the Cinquecento, the timing couldn’t have been better. This was Italy’s miracolo economico. People found they had money to spend, and the state had money to build. Thousands of kilometres of highways were built across the country, and although the Cinquecento was heralded as the ultimate city car, able to navigate the narrow vicoli of Italian towns, it was also used as an important way to get out into the countryside.

For better or for worse, today Italy is one of the most car-centric nations in Europe. Virtually every household owns one, and parked cars fill up disproportionate amounts of public space. The proliferation of cars in Italy is in large part thanks to Fiat and the Cinquecento, which put car ownership into the hands of millions for the very first time. That’s a big feat for a small car.

Photography courtesy of Fiat

Get a curated collection of design and architecture news in your inbox by signing up to our ICON Weekly newsletter