The Nike Safari in orange

The Nike Safari in orange

The humble trainer is now the default footwear for all ages, nationalities and genders, accepted well beyond the sports field to the workplace, catwalk, and (most) nightclubs. So how has it stayed so fresh, asks Guy Bird.

In the early days of their existence, sneakers – or trainers as the British prefer to call them – were merely a type of footwear for playing various sports. After the Second World War, less formal and more casual fashions blossomed via American youth culture and made one of the few trainers then available – Converse’s canvas high-top ‘Chuck Taylor’ All Star – a household name, used far from the sporting arena and valued as much for its comfort and style. Worn by everyone from Elvis to Warhol, Converse popularised the idea that trainers could be for everyone. It still sells about 100 million All Stars a year – not bad for a design that hasn’t changed much since 1917.

What did change is the wider proliferation of trainer designs in the 1960s and 70s, often endorsed by high-profile sportsmen – the 1965 Adidas Stan Smith and 1978 Diadora [Bjorn] Borg Elite are two tennis examples still sold today – which started to create a culture around the different types and styles. This increased range created interest, demand and in time collectors, who in turn made trainer manufacturers innovate to stay fresh. In the US this obsession developed around the more distinct shoes that street, college and pro-basketball players started to wear from the late 1960s, as self-proclaimed sneaker addict and expert Bobbito Garcia describes in his book, Where’d you get those?: ‘Whereas the sneaker fiend was a societal anomaly in the 70s, by the late 80s sneaker fanatics were common. It became normal to buy sneakers not when you needed to replace your old ones, but whenever you pleased. You weren’t chastised for having more than five or ten pairs at a time. The revenues generated from all this led to more development. A technology race ensued among sneaker companies.’ In the UK the trend was particularly strong among early-1980s football fans, especially those who travelled to follow their teams to European games, picking up rare continental styles there, before parading them on the terraces when they got back. Due to the comfortably stylish and well-branded footwear (and sportswear) they chose, they got the name ‘casuals’ and casual style is still going strong today well beyond the football world.

The Adidas NMD in with red and blue detailing

The Adidas NMD in with red and blue detailing

While some, including Garcia, have argued this proliferation led to a dilution of quality and classic elegance, there’s no doubting that major innovations took place as a result. Classic examples include the 1984 Adidas Micropacer which had a sensor in the toe area to record distances, average speed and calories burned displayed on an LCD screen built into the tongue flap; the rare-groove 1985 Nike Air Sock Racer that predated the trend for almost fully-woven uppers by almost three decades; and the 1993 Reebok Insta Pump Fury, where the laces were replaced by a front panel that could be inflated to keep the foot in place.

As collectors increased demand for rarer original vintage models, trainer companies responded by re-issuing more of their classics, a great example being the 1969 Adidas Superstar. Originally launched as the world’s first low-cut leather basketball trainer, it was made famous again by Run DMC’s 1986 rap classic My Adidas, and it’s rugged ‘shell-toed’ shape was still the best-selling trainer of any brand in the US as recently as 2016. Indeed, in the second decade of the 21st century, trainer endorsements by musical heroes – Kanye West with Adidas and Rihanna with Puma are two of the most high-profile – are as important, if not more so, as those by sportspeople and reflects the major trend of ‘athleisure’, trainers used for athletic and leisure lifestyles. According to market researcher Technavio, quoted in BusinessWire, this segment had the largest share (27%) of the global sports footwear market in 2015 – running shoes only represented 21% – and was still number one in the US in 2017. Estimates of the value of the global athletic footwear market vary but Grand View Research’s 2017 figure of $64.3 billion seems conservative, with increasing enthusiasm for sport, fitness, greater disposable income and easy access via e-commerce all cited as reasons for the rise (predicted to increase by 5 per cent per year until 2025). Whatever figure you quote, trainers have become big business, with mergers and acquisitions aplenty, including Nike buying Converse in 2003 and Adidas purchasing Reebok in 2005. Trainers have become deemed worthy of cultural appraisal and veneration too, as 2015’s The Rise of Sneaker Culture exhibition at the Brooklyn Museum attested.

The classic Adidas Superstar in its traditional monochrome design

The classic Adidas Superstar in its traditional monochrome design

Even the fashion world has taken note. Yohji Yamamoto’s long-standing Adidas Y-3 range is one of the joint-industry collaboration success stories yet although most high-end fashion labels from Louis Vuitton to Balenciaga have got in on the act, their high-priced takes on trainer style have often failed to convince. Indeed, within fashion circles, classic styles including the 1982 Nike Air Force 1s are arguably more popular than the clumpy ‘dad trainer’ pastiche currently pushed by fashion brands. They’re certainly more accessible, as women’s fashion weekly Grazia reported in April 2018: ‘Myth #1 about fashion people: they live in wince-worthy heels. In reality, even the most high-maintenance editor is more likely to be found sporting decidedly low-maintenance trainers. Myth #2: they don’t always wear shoes that cost a month’s rent. And the way to wear them? In box-fresh all-white with anything but sportswear.’

In terms of technology transfer, trainers have had a considerable influence on other industries, from car interiors to textiles, and vice versa. Nike’s 2012 Flyknit Racer is a great example with its virtually seamless upper created from yarns and fabric engineered in different ways and depths where most needed for strength and flexibility. Only months later Adidas launched its Adizero Primeknit, weighing just 150g for the 2012 Olympics.

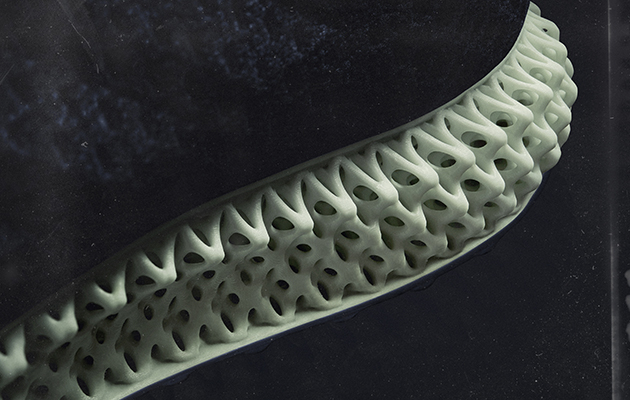

The high-tech heel of the Adidas Futurecarft

The high-tech heel of the Adidas Futurecarft

These knitting techniques have been a breakthrough from a sustainability standpoint too, as trainer magazine Sneaker Freaker explains: ‘Compared to cut and sew footwear, Flyknit construction is said to reduce the waste left over from each shoe by about 60%, due to the fact that there are no offcuts. Between 2012 and 2016 Nike has reduced waste by over 1,500,000kg. Four years after the introduction of the manufacturing, Nike completed their transition of all core production yarns to recycled polyester.’ Smaller makers wanting to reduce the environmental impact of trainers have also sprung up. Australian brand Feit was launched in 2005 selling hand-made trainers using traditional shoemaking techniques produced in small batches via an online portal – to cut out the middle man – and using sustainably sourced uppers and natural crepe soles. While far from cheap – its latest Runner shoes retail at £400 – the company’s success is reflected in the fact that it now operates a shop in New York and has branched out into shoes, boots and accessories.

The original Nike Flyknit spawned a new style of trainers

The original Nike Flyknit spawned a new style of trainers

The trend for longer-lasting materials has also seen renowned English shoemaker Grenson team up with the classic New Balance brand to supply leathers for several new interpretations of the 1988 576 runner. Again, these are high cost but also high quality, aimed at longevity of ownership, just like a pair of well-made shoes. At a lower price point, New Balance has made much of its long-standing ‘Made in England’ and ‘Made in USA’ ranges, promoting the use of better materials (and implied better workmanship through longer-held skills) than more recent, lower-cost manufacturing sites in Asia and elsewhere.

The minimal Feit Runner in leather

The minimal Feit Runner in leather

The industry has become more gender-conscious too. Trainer culture has always had many women within its ranks, but the industry has only recently started releasing more ranges in female sizes. As this gets rectified, it has in turn spawned female-focused trainer stores around the world, one of the most recent being Kickslove in Deptford, south-east London. Nike has launched Unlaced, a new shopping platform tailored for women.

Of the most recent technological advances, Adidas’s Futurecraft 4D trainers stand out. But while it garnered serious column inches in 2017 for its single-component midsole design and had a limited release in early 2018, it was more about showcasing the concept of a future where it could 3D-print soles specifically to each customer’s feet than bottom-line sales in the present. More real-world and in widespread production is the Boost sole developed by chemical giant BASF, which resembles thousands of styrofoam balls that the firm claims help to ‘return energy’ to the user. While the serious athletics magazine Runner’s World is slightly dismissive of trainer marketeers’ bolder claims, it does concede the technology has upsides, combining ‘the softness of a cushioned shoe with the powerful, quick turnover of a responsive one’.

In shades of brown and black: the Grenson X New Balance

In shades of brown and black: the Grenson X New Balance

And although the Boost sole has been employed to great acclaim on the ever-expanding Adidas NMD range first launched in late 2015, the NMD’s success is not all about technology. As James Trivunovic from UK trainer chain store size? Pointed out in an interview with the Highsnobiety streetwear website the NMD’s contemporary look is down to the fact that ‘first and foremost it doesn’t look like a performance shoe’. And therein lies the success of the humble trainer. Over the decades it’s gone from performance-enabling and comfortable, to high-tech, high-fashion and sometimes even rebellious. That it is, in 2018 a multi-billion pound industry is testament to its ability to morph and to offer something for every walk of life and budget. Trainers reflect a more sporty, casual, comfort-seeking, but no less fashion-conscious society.